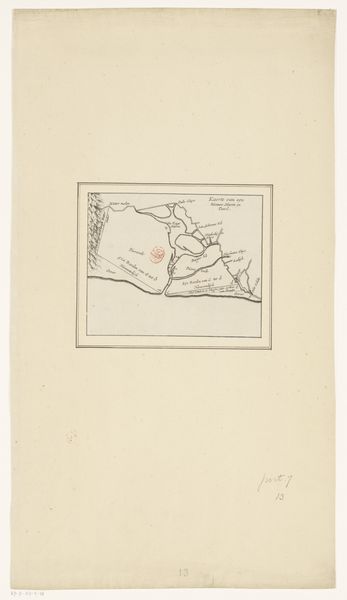

drawing, print, paper, ink, graphite, pen

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

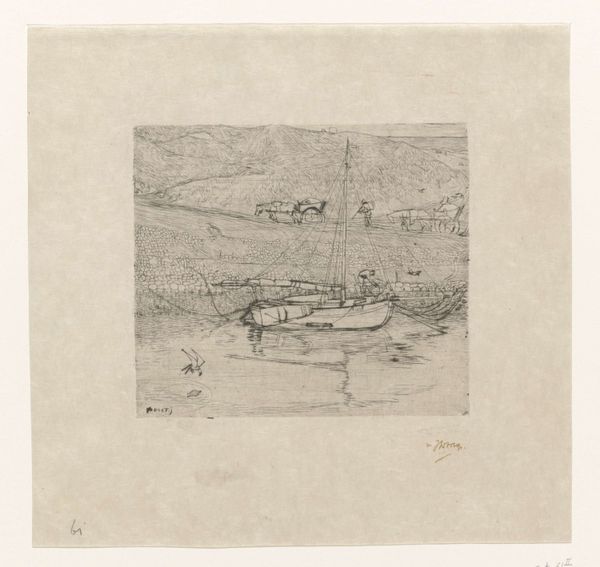

etching

#

figuration

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

graphite

#

pen

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: 122 × 128 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is an undated work simply titled *Putto*, currently at the Art Institute of Chicago. It appears to be a drawing made with pen, ink, and graphite on paper. It's interesting how this small figure is so vulnerable. What do you see in this piece that informs its significance? Curator: It’s fascinating to consider how representations of the putto have shifted across time and culture. This drawing, with its Renaissance echoes, invites us to question how notions of innocence and cherubic forms have been employed to legitimize power structures. Consider the way the seemingly innocent putto has historically appeared in contexts ranging from religious iconography to symbols of imperial authority. Editor: That’s a complex viewpoint. I mostly saw the baby-like form as conveying simple vulnerability. Are you saying that reading is too naive? Curator: Not necessarily, but it's important to examine the broader sociopolitical implications. Whose vulnerabilities are we taught to see, and whose are systematically ignored? The putto, often a symbol of purity, existed in a world far from pure, one marked by class divisions and gender inequality. Think of the labour behind artistic patronage. Where did the materials to create the ink and paper come from, and who were the human resources responsible? Editor: So you are less concerned with the artist’s intention and more about the cultural forces at play during its creation? Curator: Indeed. Understanding the social milieu helps reveal how artworks participate in broader narratives of dominance and resistance. The putto, rather than simply existing as a neutral representation of infancy, actively contributed to shaping perceptions of power dynamics. Can we appreciate the skill while also questioning the value systems it represents? Editor: This makes me realize how limited my thinking was. I’ll never look at seemingly simple art forms the same way again. Curator: And that is how we foster a more critically engaged relationship with art and history. Recognizing these interwoven strands, of aesthetics, power and historical circumstances helps art become more meaningful.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.