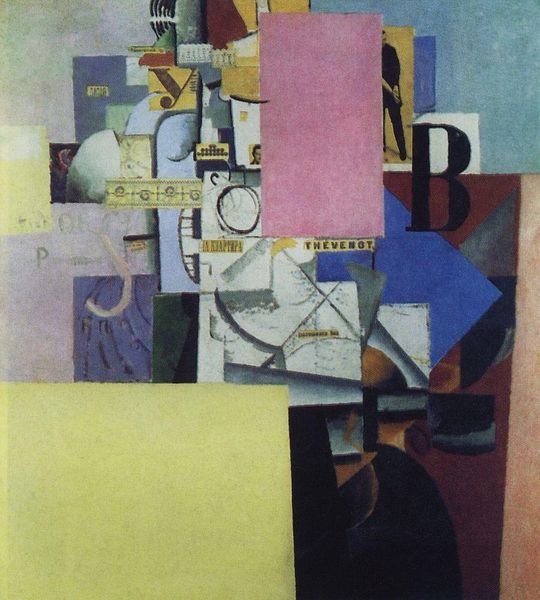

Copyright: Public domain

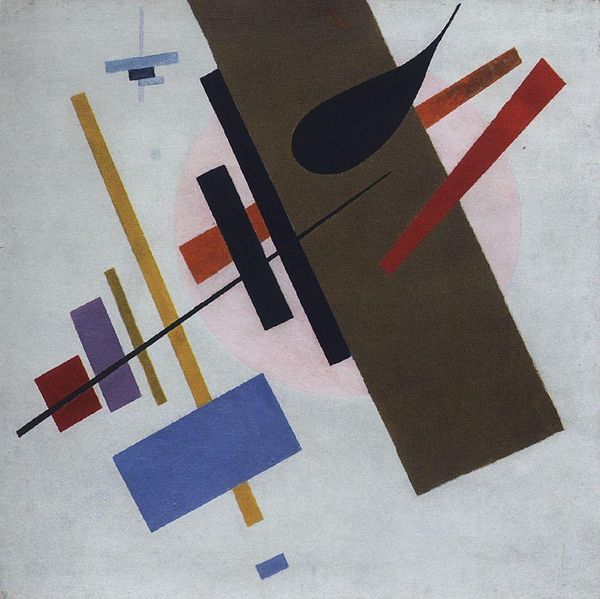

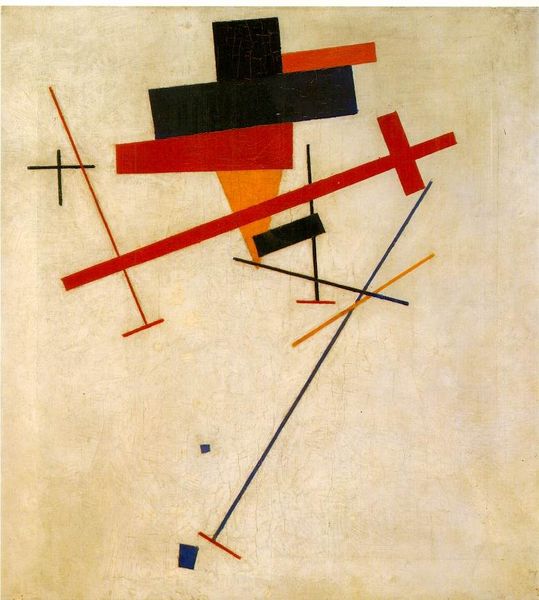

Curator: Here we have Kazimir Malevich’s "Suprematism," painted in 1916. What strikes you about it? Editor: A sense of liberation, almost weightlessness. These geometric forms – squares, triangles, lines – float ethereally across the canvas. Is that intentional, this sense of spatial ambiguity? Curator: Absolutely. Malevich sought to distill painting to its purest form, a non-objective representation of feeling. The term "Suprematism" itself refers to the supremacy of pure artistic feeling over representational depictions. It’s about reducing art to fundamental geometric forms and a limited range of colors. Editor: The severe geometry does speak volumes, in its own way. Look at the recurrent black squares; black is such a loaded color—an emblem of mourning and of anarchism, and the void. How do you feel it factors here? Curator: Black operates here, as Malevich intended, to reject the established art world in order to begin again, at zero, by reducing pictorial form down to just a handful of abstract building blocks and non-colors. Editor: Still, I sense yearning. The shapes are so spare, stark—they make me feel forlorn. Is that what Malevich meant? Curator: Perhaps. Certainly the limited color palette, which mostly stays neutral, creates a unique emotional register, neither happy nor sad, per se. More…suspended. This echoes the shift occurring in Russia at the time. Editor: Indeed. Knowing the cultural context, Malevich paints on the cusp of monumental social upheaval. This painting mirrors that; an old order dissolving, awaiting the construction of a completely new order. Curator: Yes, and what remains fascinating about Suprematism, is that even decades later, we may not be sure exactly what that final shape looks like. That promise of a utopia still lingers with Malevich. Editor: I'll leave pondering the possibility that in the interplay of form, color, and absence, lies the true meaning. It resonates on a deeply subconscious level, which I realize is how symbols still act on us. Curator: Precisely, and even beyond Malevich’s revolutionary theory, what remains palpable today is simply the beautiful, strangely arresting arrangement of those simple forms.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.