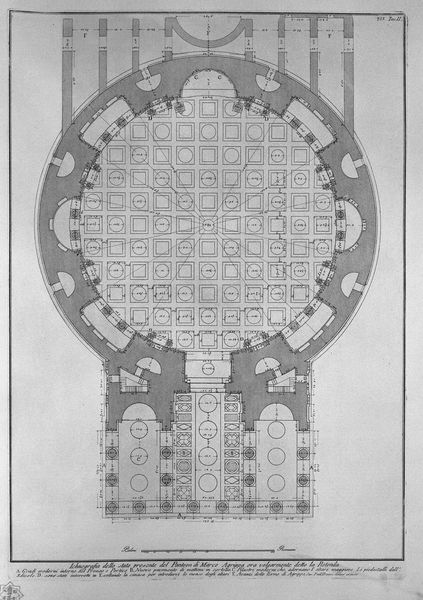

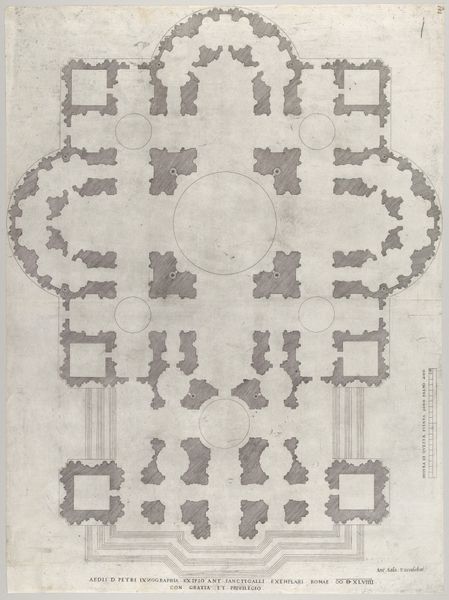

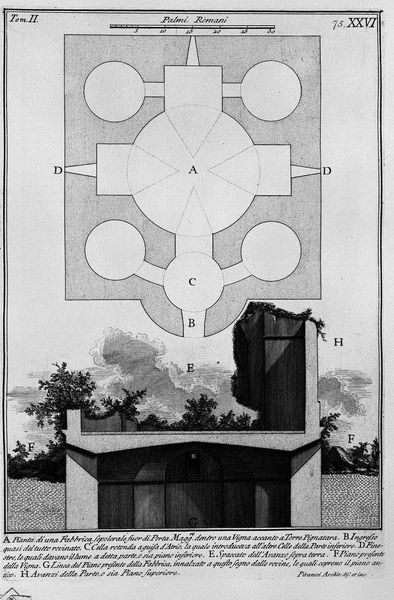

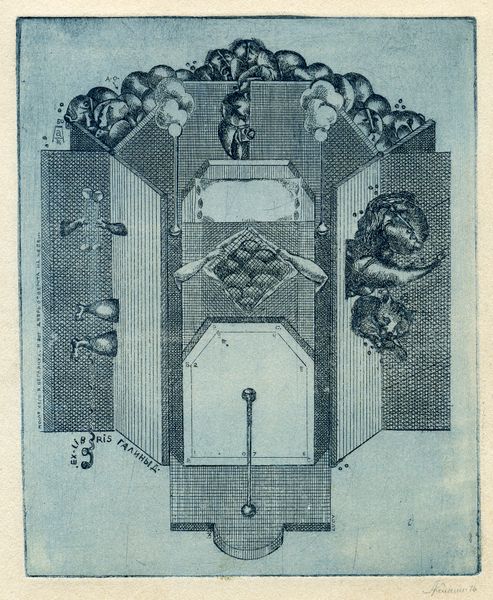

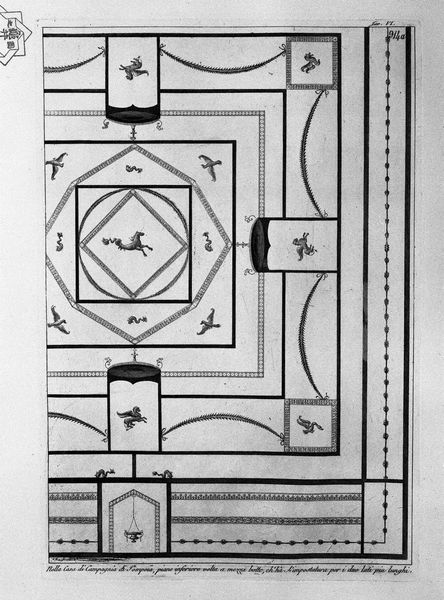

The Roman antiquities, t. 2, Plate XLVIII. Plan of some burial chambers discovered the year 1751 in the Villa of the five located outside Porta Salaria near Grotta Pallotta.

0:00

0:00

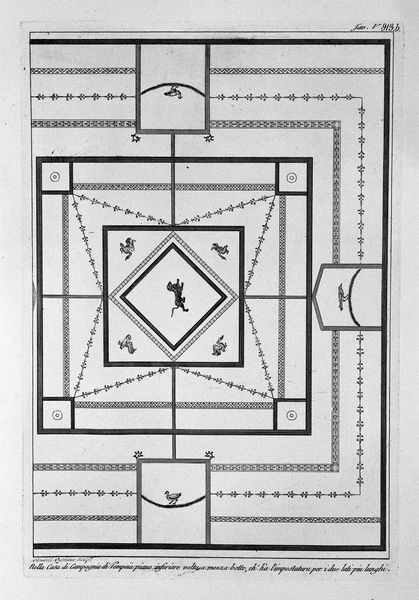

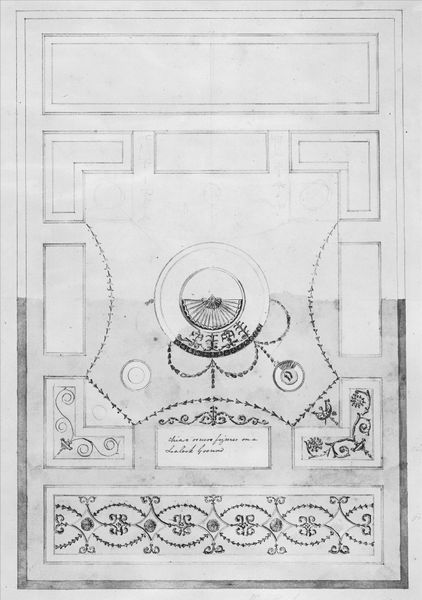

drawing, print, paper, ink, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

# print

#

paper

#

text

#

romanesque

#

ink

#

geometric

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

architecture

Copyright: Public domain

Editor: Here we have Giovanni Battista Piranesi's "The Roman antiquities, t. 2, Plate XLVIII. Plan of some burial chambers discovered the year 1751 in the Villa of the five located outside Porta Salaria near Grotta Pallotta." It's an intricate print using ink on paper, and I'm immediately struck by the geometric precision of the layout. What do you see in this piece beyond its obvious architectural elements? Curator: I see a map of power and remembrance. Piranesi wasn't simply documenting architecture; he was highlighting the layers of history and how societal structures impose themselves, quite literally, on the landscape and on memory. Notice how he juxtaposes different scales and perspectives, almost as if the weight of Roman history is pressing down. Editor: You mean like, how the ground plan feels both precise and oppressive at the same time? Curator: Exactly. The rigid lines and detailed measurements speak to a desire for control and understanding. But consider the social context. Who were these burial chambers for? What did their placement and design signify about their status in Roman society, and how does Piranesi's meticulous recording perhaps unintentionally amplify that social hierarchy? Editor: So it’s not just about Roman history but about who gets remembered and how their story is told – or in this case, mapped? The inscriptions of the soldiers you mentioned earlier. Curator: Precisely. And the fact that they were Pretorian guards points to a specific kind of power being memorialized. How might this representation challenge or reinforce existing power structures? Consider the politics of archaeology. Who unearths these stories? Whose narrative is privileged? These plans, so clinical in appearance, conceal a whole history of power dynamics and societal inequality. Editor: That's a very different way to look at an architectural drawing! It makes me think about how even seemingly objective documentation can be inherently political. Curator: Indeed. It's a reminder that art, even in its most technical forms, can be a potent vehicle for ideological messaging and the inscription of social structures. We are standing above that text; let's not ignore those buried beneath.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.