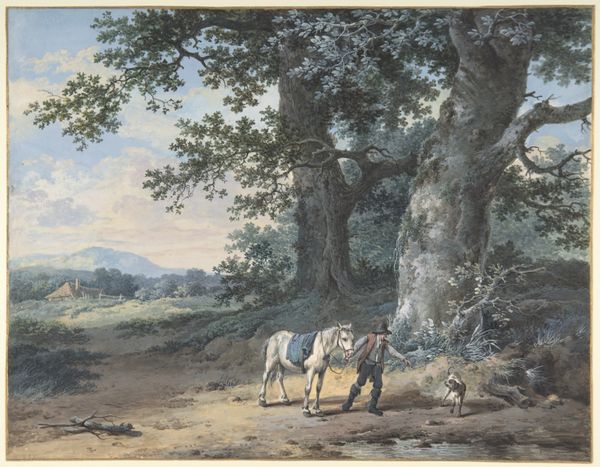

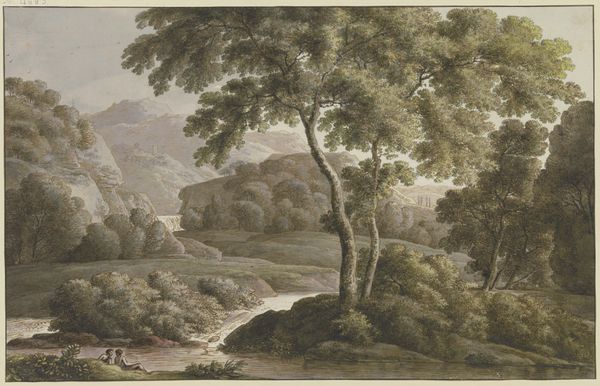

Heuvelachtig landschap met zware bomen en menselijke stoffage 1759 - 1842

0:00

0:00

watercolor

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 405 mm, width 486 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Pieter Pietersz. Barbiers’ “Heuvelachtig landschap met zware bomen en menselijke stoffage," made sometime between 1759 and 1842, in watercolor. It’s got a kind of pastoral peacefulness to it. What strikes you about this piece? Curator: The romantic idealization of the landscape here begs us to consider what's *not* shown. Barbiers’ world feels serene, yes, but what about the socio-political unrest brewing during his lifetime? Where are the traces of revolution or the early stages of industrialization that were reshaping the very fabric of society? Does this focus on an untouched landscape act as an escape? Editor: So, it's a curated view, perhaps? One that actively avoids the messy realities of the time? Curator: Precisely! Think about who this imagery serves. The wealthy elite often commissioned landscapes like this, a form of escapism solidifying their privilege against the backdrop of potential social upheaval. Are these "genre paintings" reflecting or refracting the lived experiences of the common person? The figures, idyllically placed, don’t seem to betray much evidence of the era's hardships. Do you think that is a reflection or an escape? Editor: That's a good point; even the farmers in the painting look rather well-fed! So, the Romanticism we see isn't just about beautiful nature, but also about upholding a certain social order? Curator: Absolutely. The “natural” world here is carefully constructed and freighted with ideology. The seeming innocence of Romanticism is precisely where its power lies, isn't it? These kinds of images normalized ways of life for the ruling class. Editor: I never really considered the politics of landscape painting before. It gives you a whole different perspective on art history. Curator: It certainly reframes our relationship to these images!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.