Waldausgang, rechts die Ruine einer Kapelle, in die ein Reiter hineinreitet

0:00

0:00

drawing, tempera, painting, paper, watercolor

#

drawing

#

tempera

#

painting

#

landscape

#

paper

#

watercolor

#

german

#

classicism

#

15_18th-century

#

watercolour illustration

Copyright: Public Domain

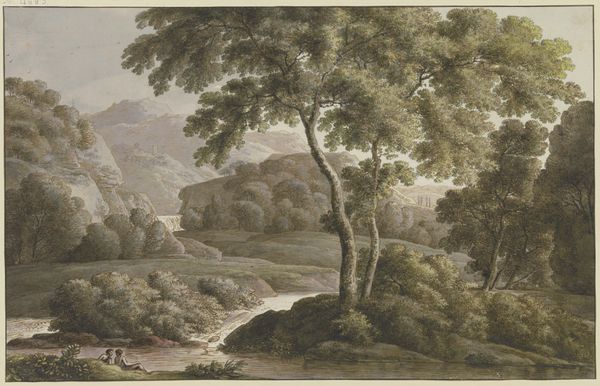

Curator: Let's take a moment to appreciate this pastoral scene titled "Waldausgang, rechts die Ruine einer Kapelle, in die ein Reiter hineinreitet," an eighteenth-century watercolor and tempera painting by Karl Franz Kraul, currently residing in the Städel Museum. Editor: My immediate reaction is how incredibly gentle it is. The colour palette is so soft, almost faded, and the figures are placed so carefully within the landscape. There's an overarching sense of peace and human insignificance in the face of nature. Curator: Yes, the artwork resonates with themes prevalent during that era, with the classicist movement, where idealised landscapes symbolized social harmony. Kraul’s attention to architectural ruins and everyday life illustrates his interest in documenting society and cultural heritage. Editor: The application of watercolor, particularly, speaks volumes. Look at the almost translucent washes, building depth through layering. This wasn't just about depicting a scene; it was about exploiting the very properties of the medium. How accessible were such refined materials and the skills needed? What was the artist’s relationship to production? Curator: Access to materials would reflect the artist's social standing and patronage networks. Wealthier artists, supported by the elite, had more resources and freedom to experiment with finer materials and detailed craftmanship. The emphasis would also be on training and the establishment of formal institutions. Editor: But think about the labour embedded within it. Where were these materials sourced, how were they processed, and what were the working conditions of the artisans that contributed to making it possible? These idyllic images often cloak very complicated and asymmetrical structures. Curator: Indeed. While the image presents a seemingly serene landscape, we can interpret it through a socio-political lens. We might consider who these figures in the artwork are and their implied social hierarchy, perhaps exploring connections to issues around labor or power at the time the art was produced. The ruin could symbolise broader political and institutional decay, inviting interpretation of the artist's own context. Editor: The ruins feel important—the work of time and labour eroding. What endures, and what fades away? Curator: Ultimately, what is remarkable is that a relatively humble tempera on paper has persisted for so long, affording us a view into a specific past moment. Editor: A testament to its material legacy—though how we choose to read its complex social texture today inevitably colours our understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.