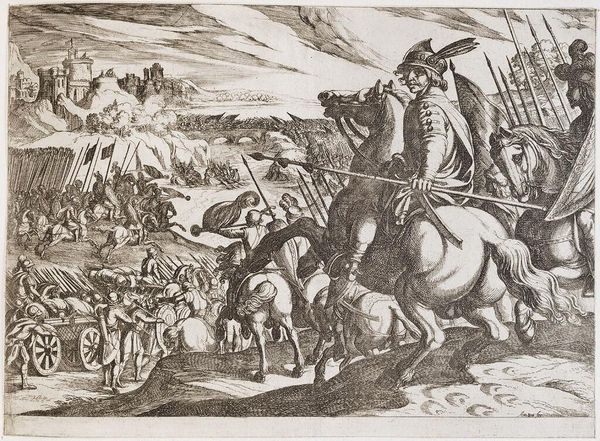

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

charcoal drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

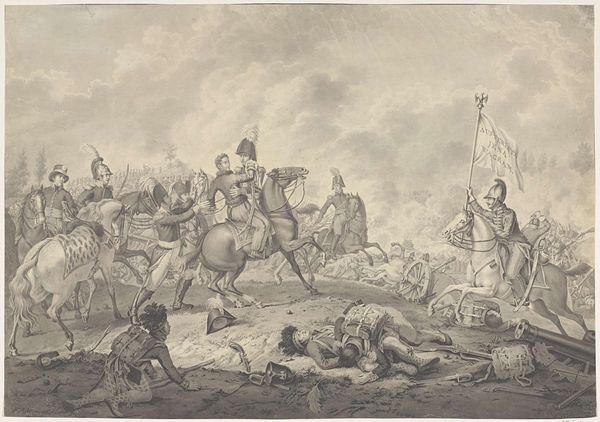

history-painting

#

engraving

#

erotic-art

Dimensions: height 456 mm, width 632 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a compelling scene! Pieter Pickaert rendered this "Equestrian Portrait of William III, Prince of Orange" sometime between 1689 and 1691. The engraving offers us a glimpse into the image-making surrounding this significant political figure. Editor: My immediate reaction is that there's a real tension between the detailed portrait of William and the somewhat sketchier rendering of the surrounding figures and landscape. It highlights the individual at the expense of a broader sense of place, doesn't it? Curator: Absolutely. And this tension speaks directly to the function of such a portrait. It was less about faithfully capturing a scene and more about solidifying power and authority in the wake of the Glorious Revolution. Consider how portraits like these functioned as propaganda. Editor: It’s fascinating to consider the engraving process itself. Think of the labor involved, the skill required to translate an image into lines on a metal plate, multiplied by each impression. What does the repetitive act of production tell us about the intended widespread distribution? Curator: Exactly. These images were circulated widely, playing a crucial role in constructing and maintaining a specific image of William III. The engraver’s hand was instrumental in translating regal ideals into accessible visuals for public consumption. Editor: And it raises the question of access. Engravings were relatively more affordable than painted portraits, making imagery of power available to a wider audience. Yet the question remains, who truly controlled the dissemination and interpretation of these images? Curator: The patronage networks certainly played a central role, ensuring specific messages aligned with the interests of those in power. But the very act of disseminating these images created opportunities for reinterpretation and negotiation within different social strata. Editor: I agree. Looking at the marks and the way they form these textures makes you think of the workshops of the period—the conditions and craft of production of images, how they affected not only art history, but economic history, too. Curator: This analysis highlights how power isn't just represented but also actively negotiated and solidified through the creation and distribution of art. A work that underscores how political agendas can be shaped and advanced through material means. Editor: Indeed. It encourages a deeper appreciation for the multilayered processes through which art assumes its roles in history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.