Fabel van de boer en zijn ezel; De zoon van de boer zit op de ezel terwijl de boer loopt 1627 - 1628

0:00

0:00

wenceslaushollar

Rijksmuseum

print, etching

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

line

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 126 mm, width 155 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

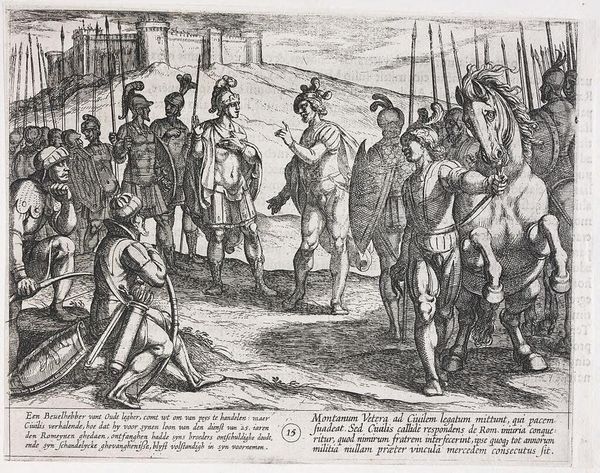

Curator: Here we have Wenceslaus Hollar's etching, "Fabel van de boer en zijn ezel; De zoon van de boer zit op de ezel terwijl de boer loopt," created between 1627 and 1628. It's a wonderfully detailed scene rendered in sharp lines. Editor: Oh, my, what a curious little drama. My immediate thought is: "That poor donkey!" It’s as if the scene has been caught at some moment of village gossip or moral conundrum. Curator: The title translates to "Fable of the farmer and his donkey; the farmer's son sits on the donkey while the farmer walks." That phrase is loaded! Do you see any familiar social scripts unfolding here? Editor: Well, you’ve got this lovely contrast. There's a visual tension between the crisp clarity of the buildings and figures and this somewhat dreamy, muted landscape fading into the horizon. The farmer leading the donkey has his head turned in what appears to be an active exchange with some townsfolk. Are we looking at the old versus the new perhaps, literally and figuratively, given their clothing? The cloaked man reminds me of judgment itself. Curator: Possibly. Hollar, being the meticulous observer, layers narrative. Consider the use of animals to carry meaning in folklore. Here the donkey seems less a beast of burden and more of an allegorical pawn—an active agent around which opinions seem to swell! Editor: Absolutely. The line work contributes, I think, to that gossamer sense of something light being blown about. Like reputation itself! I wonder if that exchange is less accusatory and more inquisitive? The son's sitting rather upright upon the donkey. Maybe a visual nudge at the "high horse"? Curator: That reading aligns. Hollar has presented us a slice-of-life fable—a social commentary woven into this seemingly simple rural setting. What would we know, even, about such a scene without that text framing? Editor: It truly would invite speculation, and potentially more projection without the written texts above and below. How remarkable to invite his viewers into a scene as the active decision-makers. The composition becomes a mirror. Curator: I’d say it succeeds then, because centuries later we’re still unpacking its visual vocabulary and turning it around in our minds. It really reveals Hollar’s deep grasp on visual storytelling. Editor: Indeed, it’s a quaint echo of eternal human foibles caught in amber through masterful lines, like looking into a particularly honest snow globe.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.