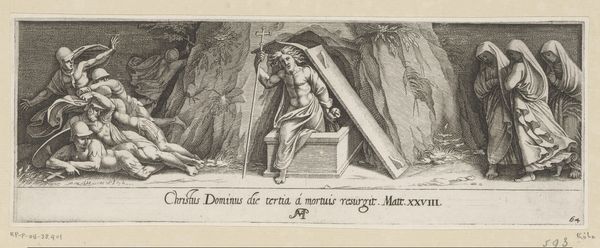

Plate 12: The Resurrection, after a lost fresco in the basamento of Bay 13 of the Vatican Loggia 1650 - 1677

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 3 5/8 × 9 7/16 in. (9.2 × 24 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have Pietro Santi Bartoli’s "The Resurrection, after a lost fresco in the basamento of Bay 13 of the Vatican Loggia," dating from around 1650 to 1677. This print offers insight into how classical themes were reimagined through a Baroque lens, reflecting the church's strategies of visual persuasion during the Counter-Reformation. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the material; it’s an engraving, a medium known for its precision. But, it is also striking for how it renders such dynamic energy; the resurrection is quite active, not just a solemn affair. Curator: Indeed. Bartoli, known for documenting classical Roman art, paradoxically presents us with something fleeting—a copy of a lost fresco. This engraving becomes crucial to understanding the circulation and interpretation of Renaissance religious art. Editor: And consider the labor! The meticulous work required to create the fine lines, the hatching, the cross-hatching. It emphasizes not only skill but the time and effort needed to propagate these religious narratives to a broader audience via reproducible media. It's industrial! Curator: It is quite deliberate in its production. Note the expressions on the figures. On one side the grieving women shrouded in robes, contrasted sharply with the violent chaos overcoming the soldiers, all pointing towards the triumphant and almost serene Christ emerging from the tomb. The composition seeks to control and direct the viewer's emotional response. Editor: The clothing tells such different stories: the practical armor tossed aside; the elaborate draping across the mourning women almost concealing their forms. But back to materials; how fascinating that the drawing itself documents what has been physically lost through time. There’s something melancholic in that preservation through process, itself a labor of hands. Curator: Precisely! This engraving allowed for a wider dissemination of religious imagery during a period of religious and political upheaval. Its public role as a didactic tool is undeniable. Editor: It makes you wonder about the social context of the engraving trade in the 17th century; who were the engravers, who commissioned the prints, and how were they consumed? What workshops and specific labor were at work? Curator: Pondering such questions indeed helps to illuminate the complex layers of cultural meaning embedded within this seemingly straightforward image. Editor: It transforms our view from the spiritual subject to the very hands that shaped and circulated its story.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.