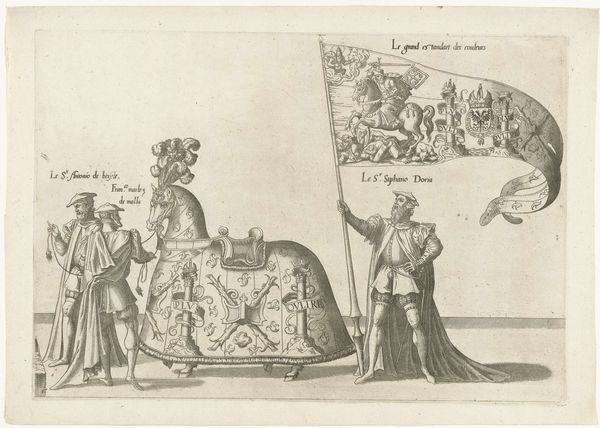

print, engraving

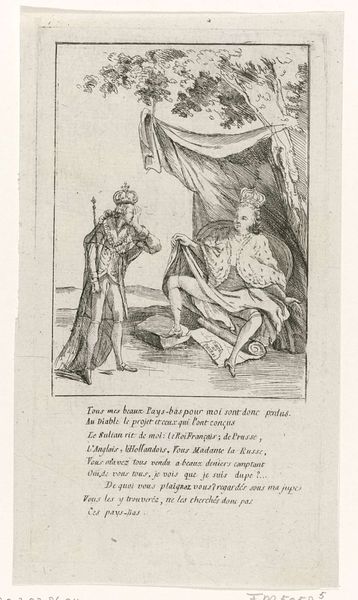

#

portrait

#

medieval

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 240 mm, width 182 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this print, it appears quite subdued and formal, almost austere in its presentation. Editor: Indeed. Here we have "Deel van de optocht, nr. 4," or "Part of the Parade, no. 4," an engraving by Joannes van (I) Doetechum dating back to between 1559 and 1619. Currently, it resides here at the Rijksmuseum. It provides insight into how public figures chose to represent themselves and their authority in print, intended for wide circulation. Curator: What immediately grabs my attention is the labor involved in creating the textures, particularly in rendering the fabrics and the heraldic emblems. Look at the intricacy of the lines to convey the different materials! There's a deliberate contrast between the heavy, dark folds of the robes and the more delicate details in the helmet plume and the banners. Editor: Yes, these prints functioned as a form of social and political currency. Displaying family crests, finery, and generally embedding status into the figures was extremely important, serving both as a commemorative and aspirational function. Curator: Exactly. Think about the social context of printmaking at that time. Engravings such as these allowed for the dissemination of specific visual messaging and also involved the engravers who became essential mediators, possessing specific skillsets. The engraver essentially determined how events were preserved for posterity, manipulating light and texture according to certain printing techniques to communicate prestige. Editor: And these images didn’t exist in a vacuum. They often reflected specific historical events or political agendas. Consider the function of public display and how prints, more so than paintings, facilitated an understanding—or indeed, a *controlled* understanding—of social hierarchy within the public imagination. It becomes a question of visibility and access, too. Who had the privilege of representation and who was actively excluded or marginalized? Curator: It prompts us to really think about how power and representation were manufactured, quite literally, in the early modern period through such works, doesn't it? Editor: It certainly does. Thank you for guiding us through the details and materiality within the history depicted here, very thought-provoking.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.