Portretten van Jan Antonisz. van Ravesteyn en Adriaen Hanneman 1750 - 1800

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 155 mm, width 102 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

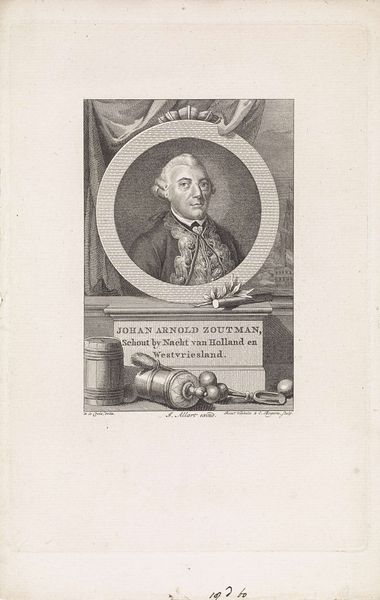

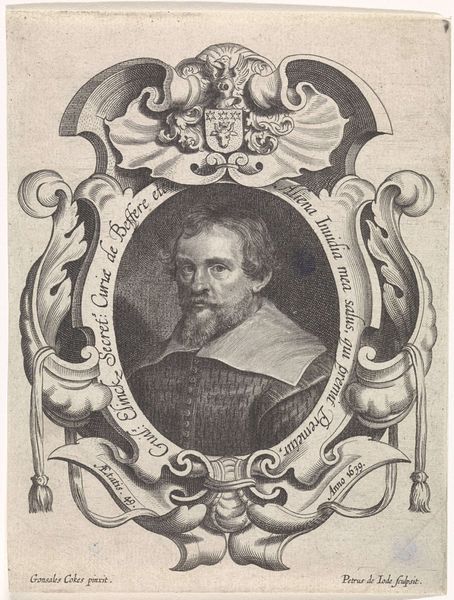

Curator: The work before us is an engraving titled "Portretten van Jan Antonisz. van Ravesteyn en Adriaen Hanneman." It's attributed to an anonymous artist and believed to have been created sometime between 1750 and 1800. The print currently resides here in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My initial impression is that of controlled chaos, the rigid lines of the engraving contrast with the baroque composition and detailing— it’s quite visually busy, isn't it? The play of light and shadow gives the figures a strange liveliness despite being fixed in print. Curator: Indeed, the "controlled chaos" you observe really underscores the historical context of portraiture in the Netherlands. Consider the rise of wealthy merchants, these images served as powerful statements of civic identity. An engraving allowed wider dissemination of the imagery for the middle class and served a social function beyond the purely aesthetic. Editor: I see your point, the engraving medium enables duplication, transforming personal commemoration into broader public consumption. The figures are staged against a background featuring classical motifs like drapery and what appears to be cupid with a rope. Curator: Exactly, it seems designed to evoke ideas of fame and lasting legacy, even perhaps hinting at their virtue being "unveiled" or made public, not to mention, their likely wealth. It would have spoken to specific social and cultural expectations of that era. Engravings such as this had the power to shape perception of political figures in the absence of other readily available visual media. Editor: Let's go back to the figures themselves—the solid figure, lifting a cup and gazing directly out as the eye is drawn to his lace collar; then there’s a medallion holding a portrait, tucked off to the side. The top figure exudes this air of civic pride, a kind of stolid bourgeois confidence, it really jumps off the surface. Curator: And just so—it is crucial to also look at what this particular artist makes a point of focusing on with these portrayals, which can offer clues as to why their version became part of collective historical memory or political identity within Holland. The level of polish can almost obscure the class function. Editor: Precisely, that initial feeling of visual density I had gives way to considering this image layer by layer. Thank you for placing this in context; it really opens new dimensions of meaning beyond the initial aesthetic read. Curator: My pleasure, I think analyzing an image as both artifact and artwork gives you the best appreciation of it!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.