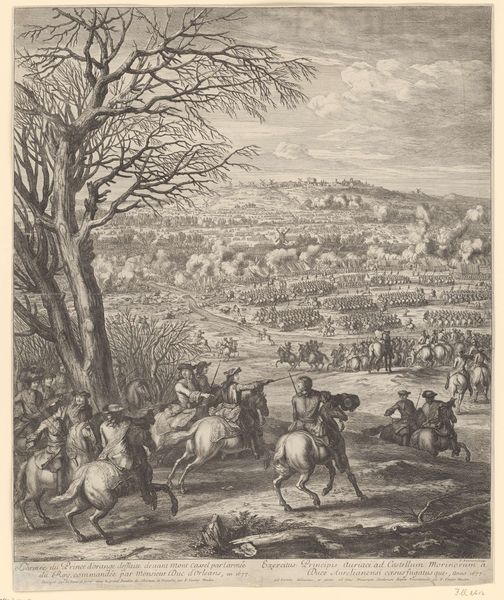

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

horse

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 586 mm, width 455 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Thomas Major's "Heuvellandschap met marktplein," an engraving created sometime between 1745 and 1749. It's part of the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: My first thought? There's a definite air of controlled elegance about it, almost theatrical. Everyone seems to be observing some kind of unspoken social ballet. Curator: It's fascinating how Major uses the engraving technique to depict depth. Notice how the figures in the foreground are rendered with darker, bolder lines, emphasizing their importance, while the distant hills fade into softer, almost ethereal strokes. Editor: Absolutely. And this market square becomes a stage. Who are these performers, and what narratives of power and class are being subtly, or not so subtly, displayed? It appears almost ceremonial, yet the presence of animals introduces chaos into this carefully orchestrated picture. Curator: The presence of horses would have been especially potent for the eighteenth-century viewer. Horses are often emblems of authority, luxury, and control over the natural world. I'm struck by how the posture and grooming of each horse likely signify their owner's status within society. Editor: The historical moment is very much tied to structures of power, wealth and influence concentrated among a privileged few. Were those represented actively engaged in colonial exploitation? Whose labor allowed them this leisure, the privilege of performing and consuming art like this? Curator: That's a valid question to consider. While Major's work might not explicitly address colonial themes, it implicitly upholds the dominant social structures of his time. It also preserves specific sartorial customs that may echo certain codes or signals. What might initially strike contemporary eyes as simply a landscape, it encodes various other meanings when interpreted in its historical, social context. Editor: This piece really demonstrates the capacity of landscapes to carry societal stories within seemingly pastoral, even picturesque scenery. What appears placid is actively doing ideological work. It helps reinforce an unsustainable status quo, by naturalizing artificial constructs like wealth or nobility. Curator: Yes, exactly. By rendering the powerful and affluent in graceful control amidst the countryside, these landscapes affirmed that privilege in their original social moment, shaping its image, then and for posterity. It reminds me again of that older idea that art holds a symbolic mirror. Editor: A mirror reflecting only a carefully chosen slice of reality, designed to legitimize power imbalances. Now, standing here in the present, what do we decide to reflect? Whose history gets told?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.