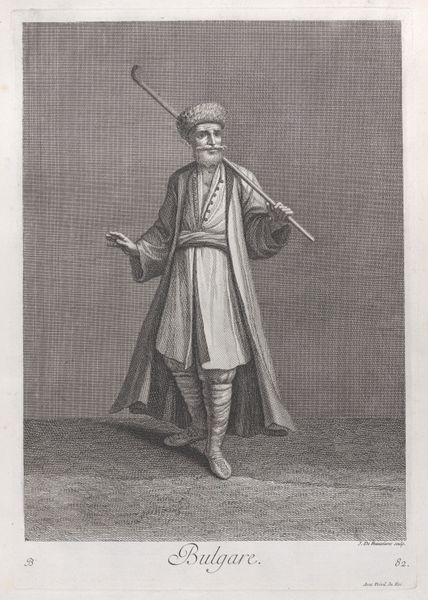

Tartare de Crimée, plate 84 from "Recueil de cent estampes représentent differentes nations du Levant" 1714 - 1715

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

men

#

line

#

portrait drawing

#

islamic-art

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: Sheet: 16 9/16 × 11 15/16 in. (42 × 30.4 cm) Plate: 14 1/8 × 9 13/16 in. (35.8 × 25 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: "Tartare de Crimee," or "Tatar of Crimea," a print made between 1714 and 1715 by Jean Baptiste Vanmour. The print captures a standing figure of a Crimean Tatar, elegantly dressed and armed with a bow and arrow. Editor: I'm struck by the serene composure of the figure. Despite the bow and arrow, there's a stillness to him, almost meditative. What draws your eye? Curator: The attire. Notice the luxurious fabric, likely silk. The fur trim on the cap suggests status. In my understanding, clothing provides key clues for the interpretation of identity in portraiture of this era, as it indicates a kind of deliberate performance. Editor: It does feel like a carefully constructed image. He holds the bow with an almost casual ease. The arrow dangling, unthreatening. I wonder about the image's purpose – is it meant to inform, to romanticize, or something else? The very act of representation holds colonialist power, even here. Curator: Vanmour was known for his depictions of life in the Ottoman Empire. He lived there for a time. The meticulous rendering hints at both observation and idealization, so in many ways it's more about the artist, and patron. The arrow almost feels less a tool and more a badge, don’t you agree? The line is quite elegant and flowing. Editor: Absolutely. It’s that duality – observation and idealization – that makes these images so compelling and problematic. Who is this man *for*? What power does this image enact upon its subjects and viewers, both then and now? How does that contrast with our current understandings of Islamic art? It pushes the boundaries of "realism," doesn't it? Curator: It certainly does. The artwork gives us an intriguing glimpse into the cross-cultural encounters of the early 18th century, but reminds us of the way visual symbolism mediates power structures. It's more of a snapshot, than reality. It’s still such an evocative study in contrasts. Editor: Indeed. An exercise in power and projection. Thank you. Curator: A stimulating read of the piece. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.