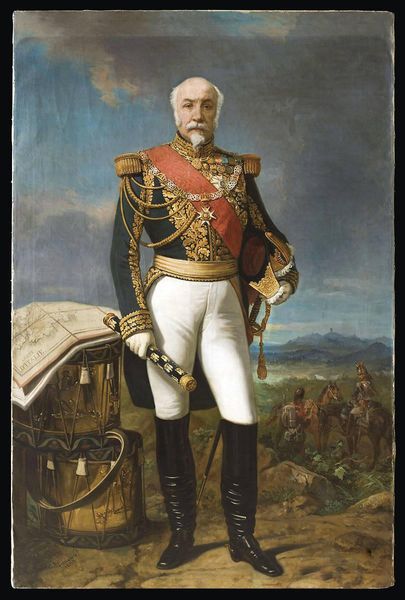

Dimensions: height 93 cm, width 62.5 cm, depth 10.5 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Nicolaas Pieneman’s 1856 "Portrait of William III, King of the Netherlands," rendered in oil paint, presents a fascinating study in power and representation. Editor: My first impression is one of theatricality. The sheer weight of that fur-trimmed mantle, the meticulous arrangement of medals and sashes… it's a very constructed image of kingship. Curator: Indeed. Pieneman skillfully uses symbols to evoke a sense of historical continuity. Consider the crown resting on the velvet cushion nearby. It represents not only the king's authority, but the weight of tradition he carries. The gaze avoids the audience but still commands respect, subtly embedding cultural memories of past leaders. Editor: Absolutely. And technically, Pieneman employs a restrained palette, dominated by deep reds, blacks and muted golds, lending the piece a somber gravitas, though some might find the academic realism somewhat stiff and conventional, there is real talent in the fabric representation, specially the fur and velvet which transmit the haptic feeling quite strongly. Curator: I see your point, but I believe it’s the formality that gives the piece its enduring impact. These carefully chosen visual motifs speak volumes. The sword at his side represents not only military might, but also the monarch’s duty to uphold justice and order. It all reinforces the collective desire of the society for an unassailable and permanent leader, projecting an archetype beyond just a singular man. Editor: Perhaps. However, I’m more drawn to the interplay of textures and the careful balancing of the composition. The rigid lines of his attire and regalia provide contrast to the soft texture of fur trimming. Note how this dynamic reinforces the figure's stable composure—an artistic interpretation of the figure of an absolute ruler. Curator: Considering our own time, observing Pieneman’s painting offers a unique moment to ponder the ever shifting relationship we have with leaders of state, or anyone really whom society grants power and control. How symbols operate on the viewer to cement, maintain, or ultimately challenge hierarchies is the crux of understanding such a potent portrait. Editor: I find myself considering the ability of portraiture in that period, especially using oils on this grand scale, to elevate the social standing of its subject in the eye of the beholder through the simple means of surface rendering, and to see how it continues to hold value for later audiences.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.