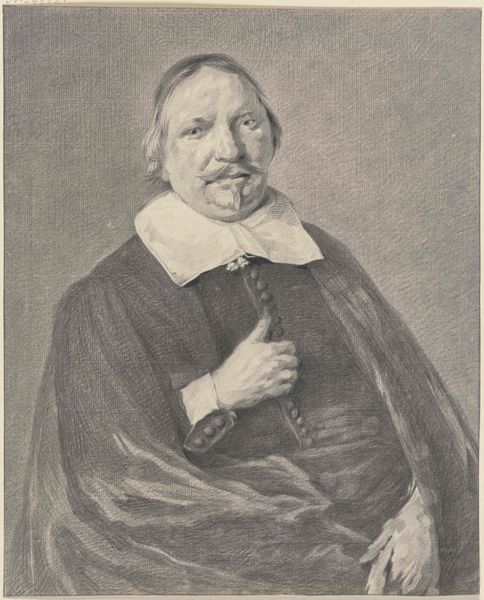

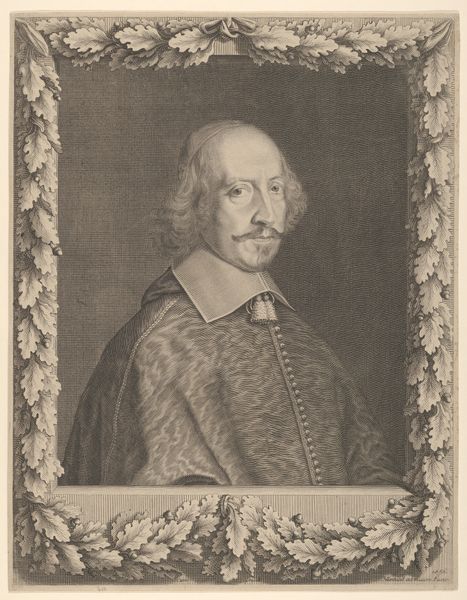

Bildnis des Robert Junius in seinem vorletzten, 48. Lebensjahr c. 1654

0:00

0:00

drawing, dry-media, chalk, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

netherlandish

#

baroque

#

dry-media

#

chalk

#

14_17th-century

#

portrait drawing

#

charcoal

#

portrait art

Copyright: Public Domain

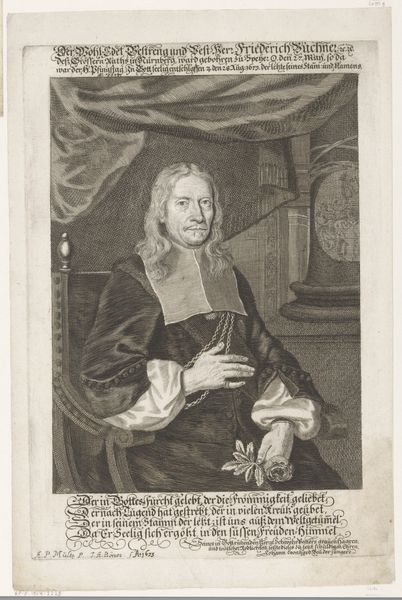

Curator: Before us we have Cornelis Visscher’s portrait of Robert Junius from around 1654, held here at the Städel Museum. It’s a chalk and charcoal drawing. Editor: Immediately striking, isn’t it? The stark contrast and the masterful rendering of light give the work a real sense of gravity and presence. The way Visscher uses line to build form, it's breathtaking. Curator: Indeed. Consider Robert Junius's position as a missionary. Visscher’s rendering subtly evokes Junius's influence in bringing reformed Christianity to the Indigenous people of Formosa, now Taiwan, amid the struggles of Dutch colonial rule. Editor: A very turbulent and consequential era, certainly. Yet, stripping away that historical layer, I see primarily the play of light and shadow—the modeling of the face, the texture of the fabric...it all pulls you in. The texture, especially; how does Visscher conjure such rich materiality with just chalk and charcoal? Curator: The intensity in his gaze seems directed right at us. It’s difficult not to think about his role in what some consider cultural imperialism, alongside whatever good he intended. His legacy has to be viewed critically. Editor: Perhaps, but I'm still captivated by the skill with which Visscher has described Junius's clothing. Look at the drape, the fall of light— it’s almost photographic in its detail. It gives the portrait a timeless quality, independent of its historical weight. Curator: The rendering can’t be separated from what it signifies, I’d say. As much as it captures the sitter’s likeness, the artwork reflects the biases and beliefs of its time, a certain acceptance of colonial ambitions... Editor: Point taken, of course. But focusing solely on that aspect risks obscuring Visscher's formal accomplishments—his extraordinary ability to translate three-dimensional reality onto a two-dimensional surface with minimal means. Curator: All art exists in an ecosystem of meanings; form is never neutral. That very 'realism' aided the Dutch East India Company's soft-power agenda. Editor: A compelling, if discomforting, view. Regardless, it's undeniable this work reveals an incredible ability to see and represent light and shadow in exquisite detail. Curator: I see it now also as a reflection of the moral ambiguities inherent in that historical period. Editor: And I, the remarkable potential of the artist’s hand to, paradoxically, both reveal and conceal complex realities.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.