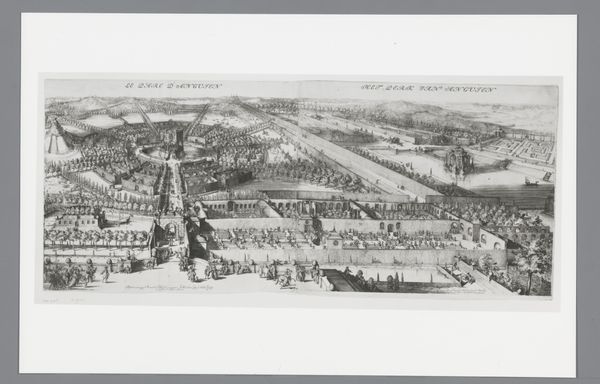

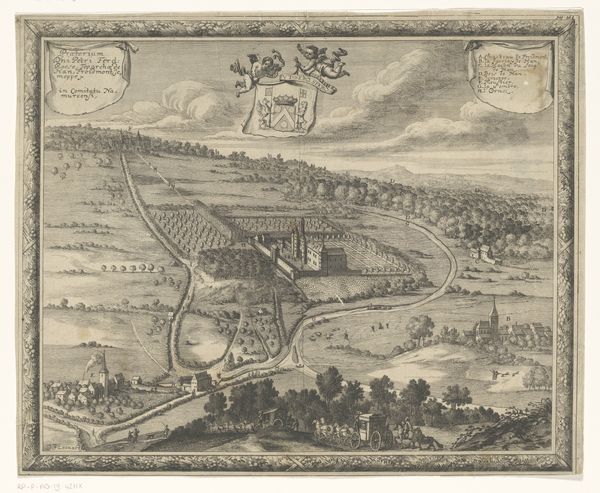

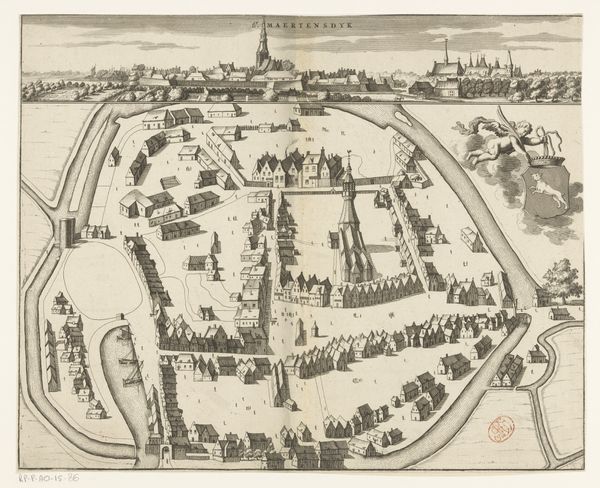

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 395 mm, width 530 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Lucas Vorsterman the Younger’s 1678 engraving, “Bird’s-eye view of Turnhout,” held at the Rijksmuseum. The level of detail is incredible, and it has a rather formal, almost propagandistic feel, given how meticulously the city is depicted. What’s your take on this work? Curator: It is propaganda, in a way. These bird’s-eye views served as powerful tools for asserting control and projecting an image of prosperity and order. Note how Vorsterman meticulously renders each building, street, and green space. Consider, too, the portraits along the top; these were prominent rulers or figures connected with Turnhout, anchoring its legitimacy through genealogy and power. Editor: So, the order isn’t necessarily accurate, but symbolic? Curator: Precisely. Think about how landscapes, even urban ones, have historically been gendered as feminine, spaces to be conquered or controlled. The 'gaze' in this bird's-eye view is decidedly masculine, a perspective of dominance looking *down* on the subject. Moreover, these detailed depictions helped rulers visualize and manage their territories. Are there other elements you find interesting? Editor: The fortifications really stand out. It speaks to the ever-present threat of conflict, even amidst all this prosperity. Curator: Indeed. It also highlights the power dynamics inherent in urban planning of the period. Cityscapes were not just about aesthetics, but about control, surveillance, and defense. We often overlook how physical space encodes social and political relationships. Editor: It's amazing to think about how much these images communicated about power, identity, and even gender roles. It makes me see landscapes in a whole new light. Curator: Absolutely. By questioning the context in which art is made, we reveal whose perspectives dominate, and, hopefully, whose have been silenced.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.