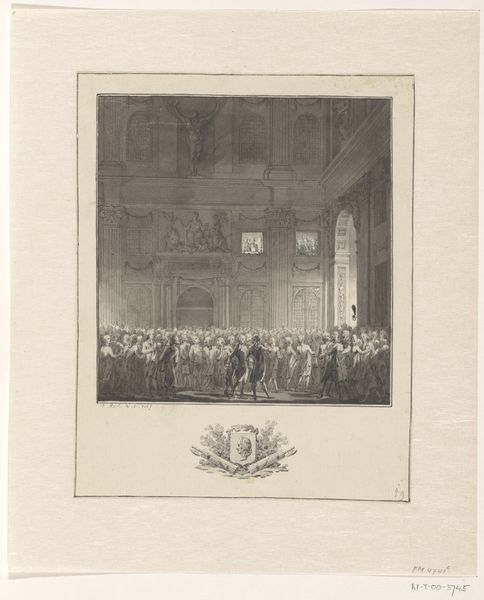

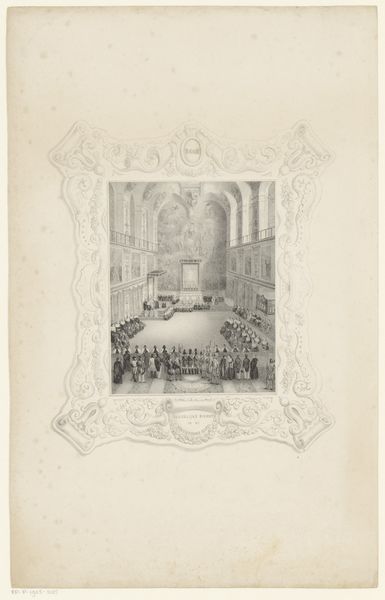

print, engraving

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

19th century

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 150 mm, width 140 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

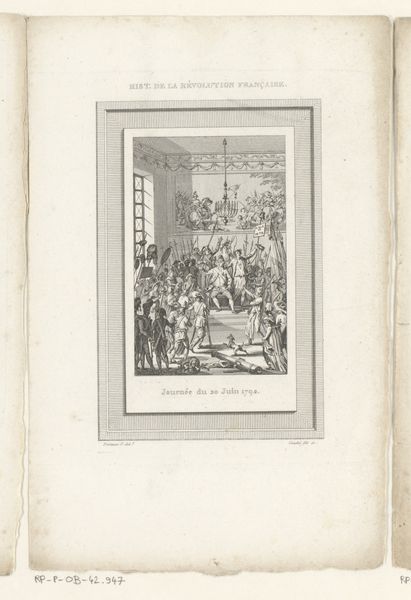

Editor: So, this is "Koning accepteert de grondwet" - "The King accepts the Constitution." It's a print, an engraving, made between 1792 and 1849 by François Louis Couché and held at the Rijksmuseum. The scene is a formal occasion but the composition is quite crowded. What's your take on it? Curator: The crowded nature you point out, ironically, highlights the very power dynamics at play. This image, produced during a tumultuous period following the French Revolution, speaks volumes about the shift – or perceived shift – in power. The architecture and the assembled crowd, seemingly there to witness and legitimize the king's action, become critical elements. What's the undercurrent, though? Is it really a moment of triumph for the people, or a carefully constructed performance? Editor: I see what you mean! It does look staged. So, what was the role of prints like this at the time? Was it just about recording events? Curator: Exactly! These prints were incredibly powerful tools for disseminating ideologies. Images like these, reproduced and circulated widely, shaped public opinion and contributed to the construction of collective memory about the revolution. Consider who commissioned this image and whose interests it served. This print could, in reality, be seen as a calculated act of propaganda, designed to project an image of royal acquiescence while perhaps masking deeper power struggles. Can we even really talk about "neoclassicism" here or do we also need to talk about power and the printing press? Editor: That's a really helpful way of thinking about it – going beyond the aesthetic to see the underlying messages about power. Curator: Indeed! Never underestimate art's political agency, especially when grappling with revolutions and reforms. Now, how does the act of looking change, understanding the conditions under which art is created?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.