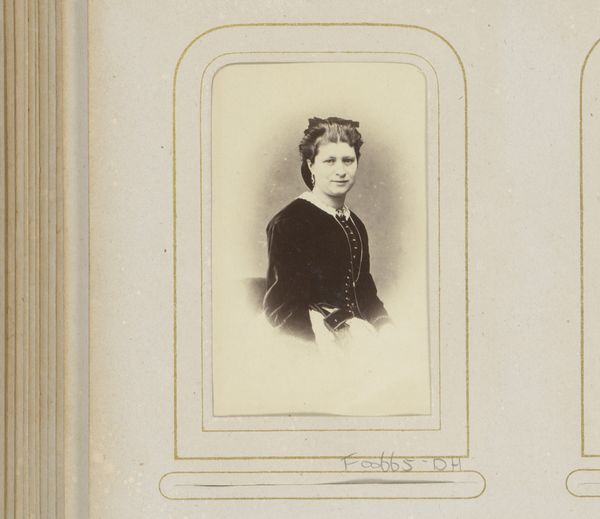

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

albumen-print

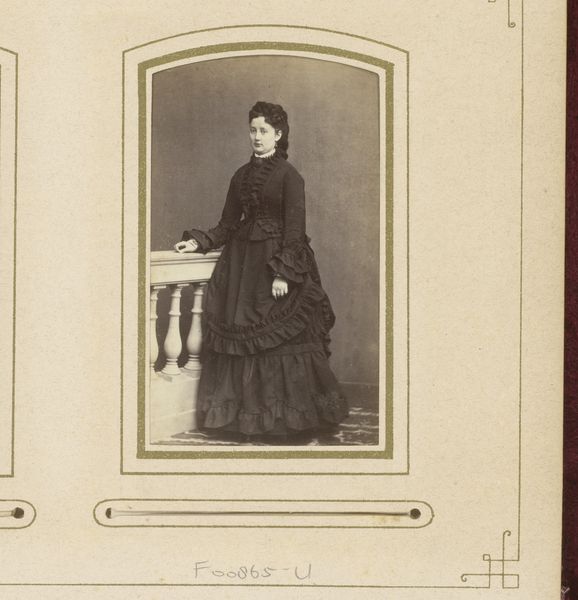

Dimensions: height 82 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This albumen print, dating from between 1860 and 1900, presents a formal portrait entitled "Portret van een vrouw, staand bij een stoel," attributed to Adolph Meister. My first encounter with the image evoked stillness—a frozen moment captured within the frame's delicate oval. Editor: There's an almost spectral quality, isn’t there? Like gazing upon a ghost from a drawing room long past. You can almost smell the mothballs. Curator: Well, consider the albumen process. It involved coating paper with egg whites and silver nitrate to create a light-sensitive surface. Then, contact printing from a negative under sunlight. The labor and materials were substantial. The purpose wasn’t to capture likeness but to assert status in a world where access to imaging was restricted by price and know-how. Editor: The resulting sepia tone is wonderfully atmospheric. The lady’s stern face gives the scene this heavy aura. Do you feel that slight tension from the picture? I find myself inventing stories about why she stands like that near the chair. She looks constrained and buttoned-up in that elaborately designed dark dress. The artist uses only monochrome but gets a surprising dynamic from shades and forms. It almost tells a story, I'd say. Curator: Indeed! The chair acts as a kind of symbolic prop, emphasizing posture, composure and hierarchy in how it situates the subject. Beyond this aesthetic judgment, the photo and materials give some clues as to where the woman fit into society. It is both social document and commercial object, after all, with Meister profiting directly from his technical proficiency. Editor: It's fascinating how an object like this, seemingly simple, contains such layers of time, context, and feeling. What was ordinary once—having your portrait taken—becomes imbued with meaning as decades pass. Curator: Yes. When we view objects of material culture from the past we should really also be thinking about what went into it, who was left out, who profits, what were the working conditions, and how the distribution affects access. Editor: That makes it even more compelling, doesn’t it? Like seeing history breathing. Curator: Indeed. Now that our time's up I think I gained some insight from looking at her and hearing what it means from your point of view. Editor: Me too! Until the next treasure from the archive, goodbye!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.