print, photography, woodblock-print

#

sky

#

narrative illustration

#

narrative-art

# print

#

impressionism

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

photography

#

woodblock-print

#

water

#

line

#

post-impressionism

Copyright: Public domain

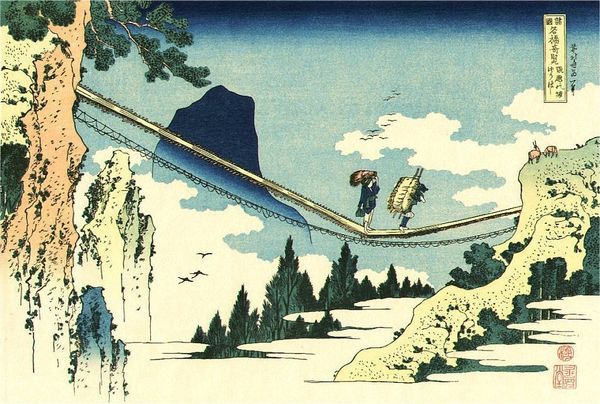

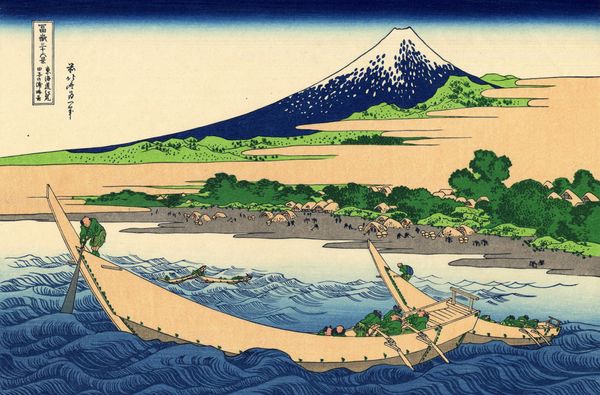

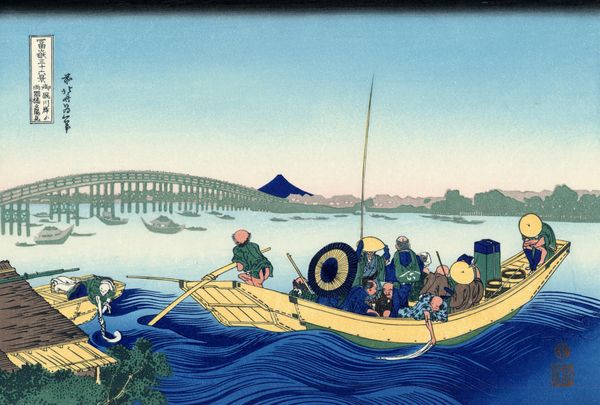

Curator: Today, we are looking at Katsushika Hokusai's woodblock print, "Kajikazawa in Kai Province," which captures a scene along the Fuji River. Editor: It's incredibly striking! The powerful diagonal lines leading down to the water command attention. The movement created is incredibly captivating and gives off an urgent and even ominous mood, but what else can we unpack here? Curator: The series that this print is from—"Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji"—was produced when Hokusai was in his seventies. It's interesting to note that the popularity of these landscapes arose alongside a developing leisure culture among the merchant classes. People were traveling more, and prints like these offered a glimpse into various locations. Editor: Travel was being commodified, and art became complicit in that. This piece specifically features two figures precariously perched on a rocky cliff, fishing. The scene speaks volumes about labor, risk, and our relationship with nature. Those strong diagonals give this art its powerful commentary on the work done within specific natural environments and under particular cultural pressures. Curator: The vantage point Hokusai chose—the steep, elevated view—really emphasizes humanity's place within the grandeur of nature. In the context of the socio-economic situation, with urban residents' romantic interest in idyllic scenery, such scenery must, nevertheless, include that era’s populations' roles and activities. Editor: Right, there's a tension between the sublime and the mundane. I wonder how contemporary viewers might engage with the historical perspective of those portrayed—the fisherfolk specifically—when observing the romantic naturalism from what’s generally considered a purely artistic point of view. Curator: Absolutely. Reflecting on these prints provides an entry point for discussions regarding social class and environment. And also how landscapes were viewed—then, as in today—by those with economic power. Editor: Understanding that landscape isn't a neutral concept, that it is inseparably yoked to both economics and people's actual lived conditions, reframes how we see and relate to the visual representation. That knowledge transforms, doesn't it, even the very colors and lines used to make the scene? Curator: It does indeed, enriching the work’s ongoing resonance through history and bringing, for example, conversations of labor or class or gender, from a new and even necessary activist’s viewpoint.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.