photography, albumen-print

landscape

photography

19th century

cityscape

albumen-print

statue

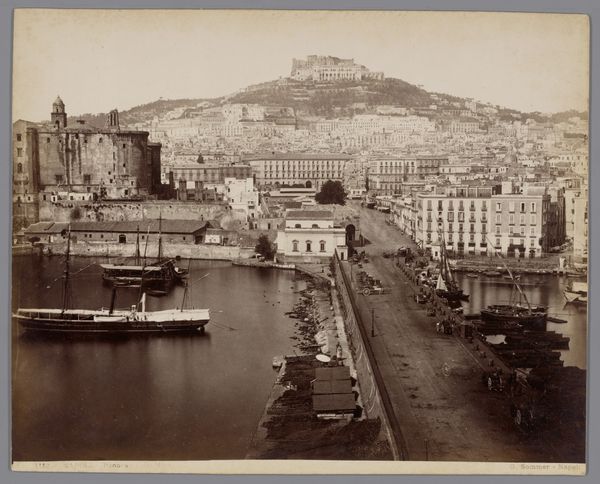

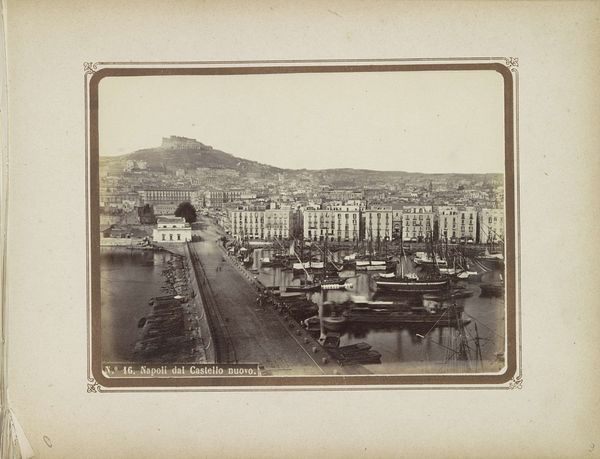

Dimensions: height 213 mm, width 271 mm, height 223 mm, width 280 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

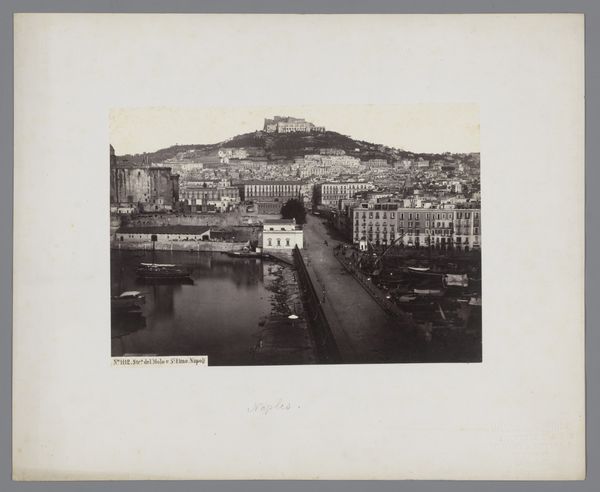

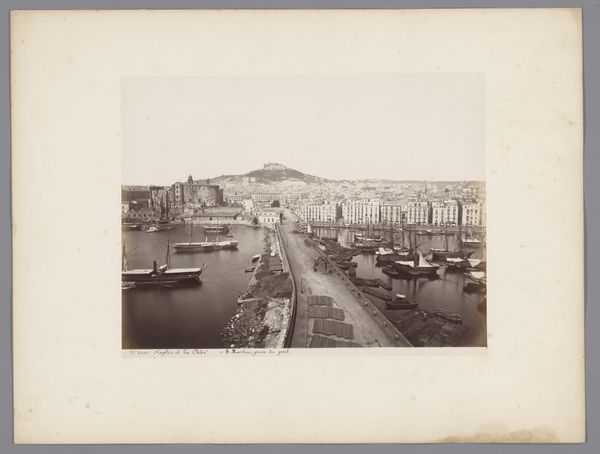

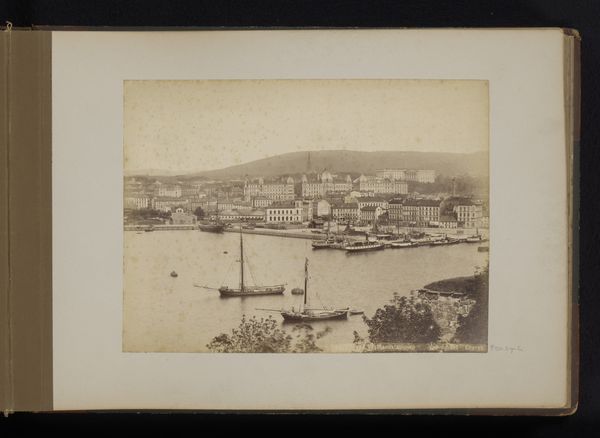

Curator: This albumen print captures the Naples shipyard, complete with the Castel Sant’Elmo looming in the background. It is by Achille Mauri and dates roughly between 1851 and 1900. Editor: Immediately, the monochromatic scale emphasizes the sharp delineation between labor and leisure. It speaks of societal hierarchies—the working waterfront against the stately architecture ascending the hillside. Curator: The photographer's framing encourages such readings. The very placement of the Castel Sant'Elmo atop that hill reinforces ideas about power and privilege. Consider too, photography’s role in codifying and distributing these social structures in the 19th century. It's a calculated visual language. Editor: Precisely, and this “language” leaves many stories untold. Where are the dockworkers, the very foundation of this city's prosperity? Marginalized in their own portrait, reduced to texture. Are we supposed to appreciate the vista or question its construction? Curator: Well, in fairness, early photographic processes like the albumen print demanded longer exposure times, hindering depictions of spontaneous action. Still, that stillness arguably emphasizes order—a prevailing ideal of the era. We have to acknowledge photography’s ambition to project objective truth, while consistently being subjected to manipulation and biases. Editor: And whose truth were they pursuing? Consider the function of cityscapes during that time – documenting progress but often obscuring exploitation. Were any workers or their families given agency, let alone payment for contributing their likenesses to such visual recordings? Curator: That's vital to remember. Beyond its technical artistry, we need to acknowledge the photograph's contribution to shaping historical narratives and understand what aspects might have been deliberately hidden, overlooked, or undervalued. Editor: Agreed. Recognizing those complexities offers avenues for critical reevaluation, positioning art as not merely beautiful documentation but rather instruments within larger ideological operations. Curator: Absolutely, acknowledging the biases encoded here reminds us to view historical artworks through a nuanced lens, mindful of both aesthetic and socio-political dimensions. Editor: Understanding this historical backdrop permits us to deconstruct visual rhetoric. We appreciate aesthetic qualities even as we contemplate societal realities documented, or un-documented within them.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.