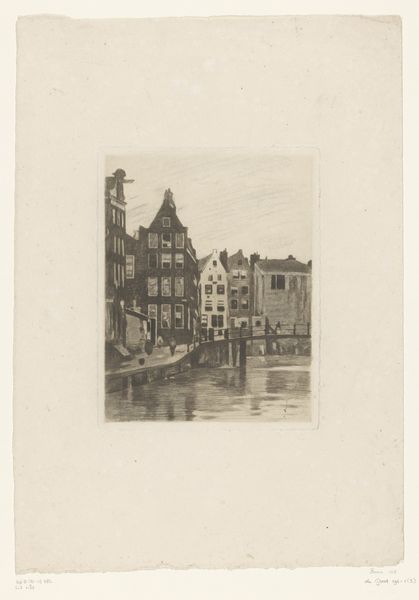

drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

line

#

cityscape

Dimensions: height 124 mm, width 150 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

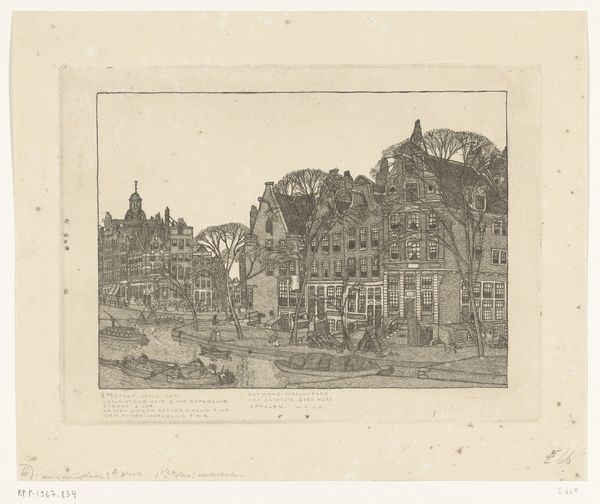

Curator: Before us is "View of the Amsterdam City Bank of Loans," an etching from 1726. The print offers a meticulous cityscape of an important financial institution in its historical context. Editor: My first impression is how much daily life it manages to capture. It's not just the grand building that dominates the composition, but all of the tiny figures going about their day along the canal and on the streets. Curator: Exactly! We must look closely at how such cityscapes from the Dutch Golden Age weren't merely objective records of the landscape, but actively shaped the perception of their city by emphasizing the industry and daily work. The etching process itself—the precise, repeatable lines—speaks to a desire for accessible reproduction, democratizing views that might otherwise be restricted to the elite. Editor: And in terms of accessing loans…what does this institution mean for various strata within society? Is this "Bank of Loans" depicted for all members of the populace or just some privileged part? It's located on a canal teeming with commercial activity – who has access to the waterfront in 1726? It makes you wonder who directly benefits from such formal capitalist institutions? Curator: Absolutely. Note also the interplay between art and craft here. Etching, as a form of printmaking, exists in a liminal space; while the artist conceives the image, the means of its production involve a level of craftsmanship, influencing the labor involved in reproducing and distributing the image, thereby implicating it within economic structures and systems. Editor: The way the scene is carefully composed is so revealing. The building isn't isolated, it's interconnected within the hustle and bustle. How much can you separate the physical spaces of production and exchange from the economic life? This isn't an isolated "object" but, literally, integrated within the daily lives of 18th-century Amsterdam. Curator: These cityscapes served, I think, a practical and a promotional function. But it is always fascinating to think about how labor is often invisible. The artist is there, and their labor is visible...But what about the underclass of workers? The whole system rests upon exploitation and social disparities that an etching alone can only subtly imply. Editor: Exactly—it becomes a document for thinking about broader societal concerns. Curator: Yes. So, looking closely at such an unassuming cityscape helps us to better contextualize both the art of the 18th century and the emerging dynamics of economy and social structures. Editor: A snapshot and a critical document.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.