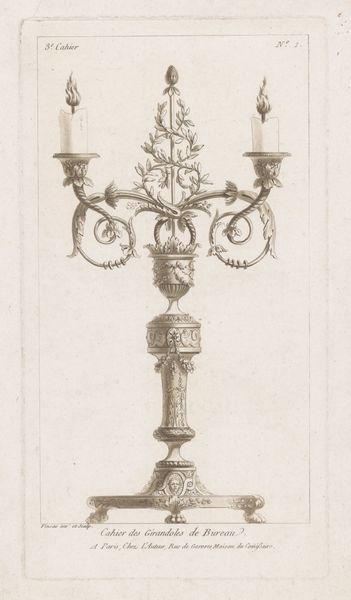

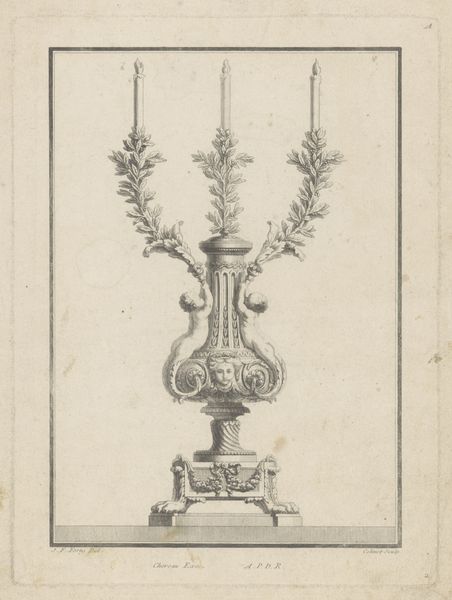

Dimensions: height 304 mm, width 189 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Girandole met saterkoppen," or "Girandole with satyr heads," an engraving dating back to between 1759 and 1800. It’s currently held in the Rijksmuseum. It’s such a delicately rendered print of what appears to be an elaborate candlestick. What strikes me is how classical the vase feels, yet the satyr heads add this unsettling element. What do you see in this piece? Curator: That tension between classical form and disruptive imagery is precisely what I find compelling. We often view decorative arts of this period through a lens of pure aesthetics and aristocratic excess, but this print invites us to consider the social and political climate in which it was produced. Editor: How so? Curator: The satyr heads, symbols of untamed nature and Dionysian revelry, are juxtaposed against the rigidly symmetrical neoclassical design. Could this be a subtle commentary on the burgeoning discontent with the established order, a hint of the revolutionary spirit stirring beneath the surface of 18th-century France? Think of it in relation to emerging philosophical movements questioning authority and tradition. Editor: So you’re saying that even something as seemingly innocuous as a candlestick design could reflect broader societal anxieties? Curator: Absolutely. The artist, Claude Dominique Vinsac, consciously or unconsciously, captured a moment of societal tension. How do you interpret the choice of engraving as a medium for this potential commentary? Editor: I guess I hadn't thought about it that way. Engraving allows for mass production and distribution, so potentially reaching a wider audience with its message? Curator: Exactly! It’s a form of visual communication that transcends the purely decorative. This piece prompts us to reconsider how we understand art's role as a social and historical document. Editor: I’ll definitely look at art from that period differently now, thinking about what unspoken messages might be embedded within them. Curator: And that is the enduring power of art history – constantly prompting us to question, reinterpret, and connect the past with the present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.