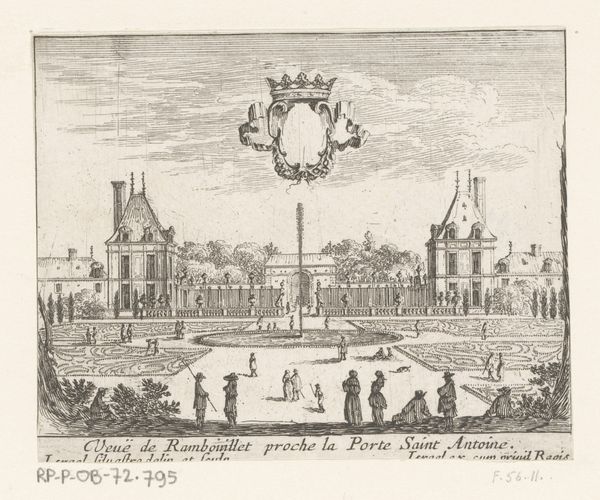

print, engraving, architecture

#

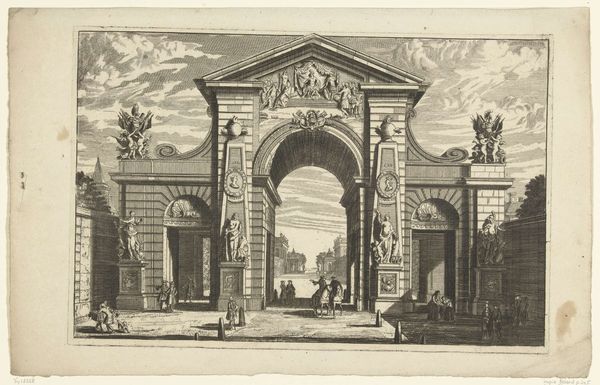

baroque

# print

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 200 mm, width 282 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is Laurens Scherm's "Triomfboog bij Fauxbourg Saint-Antoine," an engraving dating from between 1689 and 1701, found here at the Rijksmuseum. The scale and detail always strike me. Editor: My first thought is one of awe—a grand Baroque city spectacle caught in a tiny, intricate net of lines. I feel swept up in the fervor and movement but also subtly alienated, almost a voyeur to power. Curator: Power certainly seems to be the point. The inscription suggests the arch was erected to glorify the king, the "Rey." A real propaganda piece disguised as architecture and then immortalized in print! How meta. Editor: Exactly! Think about what triumphal arches have historically signified: military conquest, imperial expansion, solidifying existing power structures. It is no mere celebratory gate. Notice also how many other characters and activities fill the bottom half—an implicit illustration of the daily social hierarchies in this city. Curator: Ah, good eye! All those tiny figures, like ants scurrying around this monument to… what? Hubris? And that vast emptiness of the foreground. Are they dwarfed by the structure, or is the emptiness waiting to swallow it whole? I keep fluctuating between awe and a feeling of precarity. Editor: Precariousness is right! Baroque exuberance masks a deeper instability. Those bustling scenes feel… performative. Everyone acting out their roles in the drama of absolute monarchy, on parade! The city rendered as a theatrical stage set. The triumph ultimately appears fleeting in print. Curator: So it is not simply an artwork ABOUT power, but rather an artwork enacting it? The layers here keep unfolding and looping back on each other. Is this, perhaps, why it still speaks so loudly, even centuries later? Editor: I think so. By freezing the moment in this very self-conscious print, Scherm unintentionally reveals the manufactured nature of "triumph" itself. It compels me to examine what, and whom, those grand spectacles seek to obscure. Curator: An invitation, then, to engage not just with what's in front of us, but with everything behind it, everything it omits, everything it silences. It looks to me that both of us just became the audience in that parade. Editor: Absolutely. That kind of art making is powerful.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.