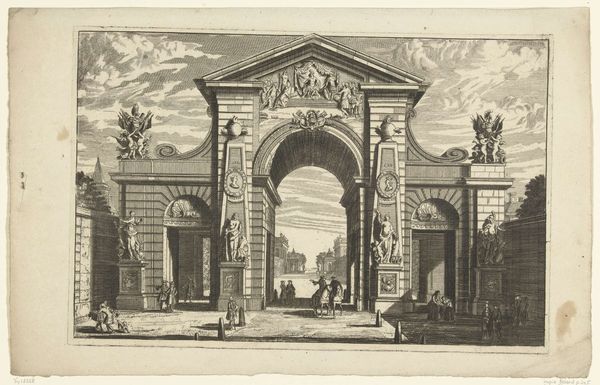

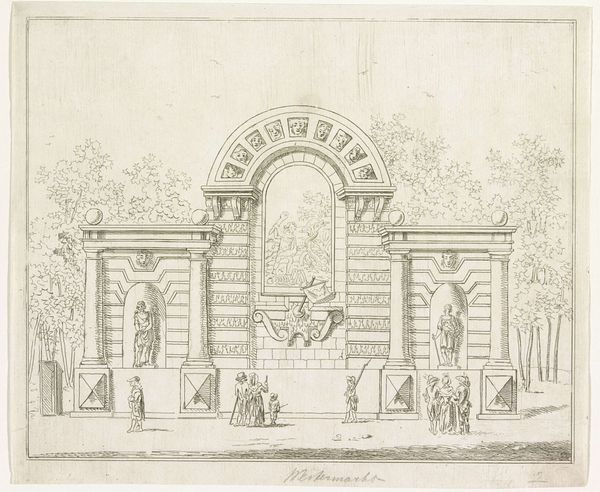

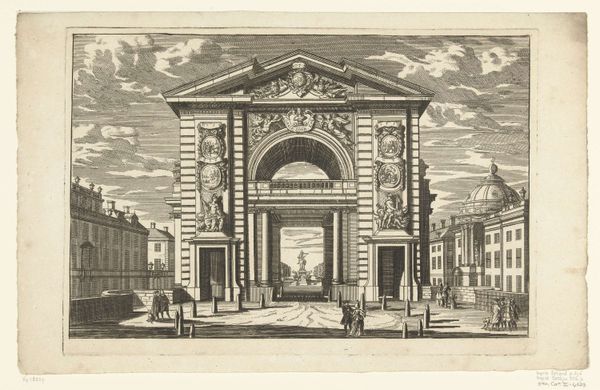

Ereboog voor Willem III, bij het Buitenhof te 's-Gravenhage, 1691 1690 - 1691

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink, architecture

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

geometric

#

cityscape

#

watercolor

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 215 mm, width 276 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: At first glance, I'm struck by the quiet grandeur of this sepia-toned drawing. It feels both imposing and intimate. Editor: You've picked up on that intriguing duality. What we're looking at is Jacob van der Ulft's "Ereboog voor Willem III, bij het Buitenhof te 's-Gravenhage, 1691", created between 1690 and 1691. It's rendered in ink and watercolor on paper. The depicted Triumphal arch was erected in The Hague to celebrate William of Orange becoming King of England. Curator: Ah, knowing that context certainly colors my reading. Now, I see this as more than just architecture. The arch, replete with statuary and topped with an equestrian figure, becomes a potent symbol of power and legitimacy at a pivotal historical moment. Consider the anxieties around succession, particularly regarding gender. What narrative does this image reinforce? Editor: It's fascinating how the artist uses familiar tropes. The geometric precision conveys order and control—classic Baroque—but there’s also an air of impermanence, typical of commemorative ephemera. The classical imagery underscores William's status by connecting him to a lineage of rulers—visual echoes of Roman emperors designed to project strength and inevitability. Curator: Indeed, we could unpack that symbolism for hours! Think about the intended audience and their socio-political expectations, even down to gendered perceptions of leadership. Did this portrayal, even as a temporary structure depicted in ink, sway public sentiment? How was it perceived by the different factions present at the time? Editor: And that's precisely where images gain their strength, acting as focal points for complex dialogues and interpretations. What struck me initially as quietude might rather be a staged serenity, a careful presentation of power rather than its authentic display. It calls into question the purpose behind constructing these kinds of displays, especially those used for consolidating monarchic power, as well as the image making that is created from them. Curator: That tension you identify really enriches the work. Jacob van der Ulft, intentionally or otherwise, has given us more than a record of an event; he has offered us a mirror to reflect on the spectacle of power itself. Editor: An intriguing intersection of art and social commentary.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.