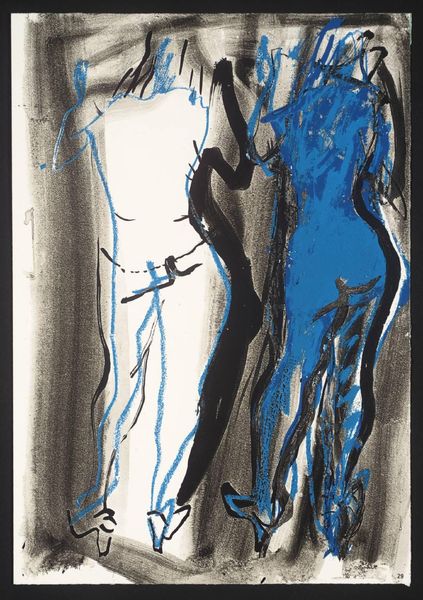

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

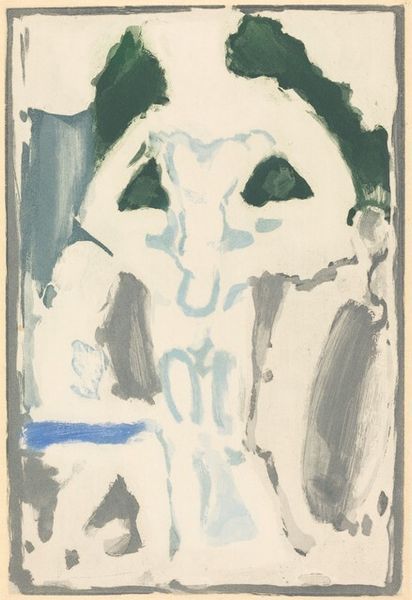

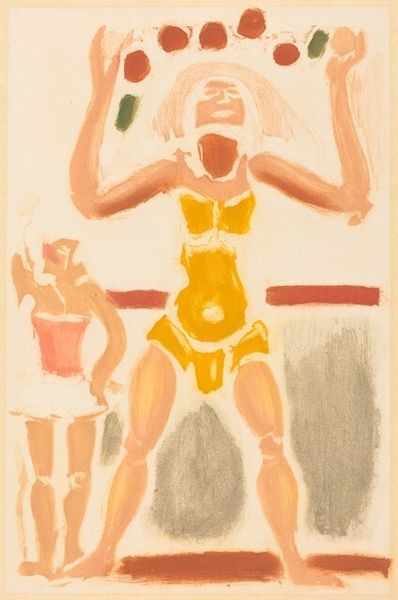

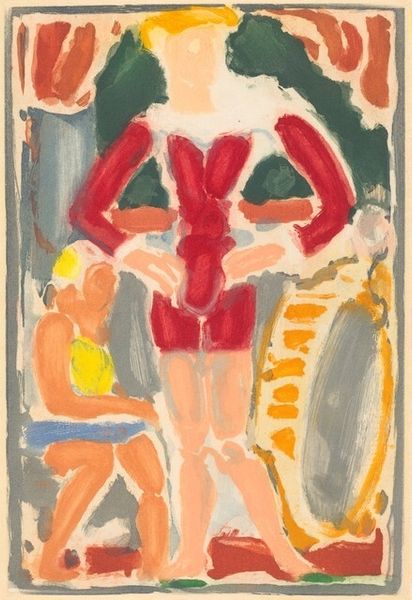

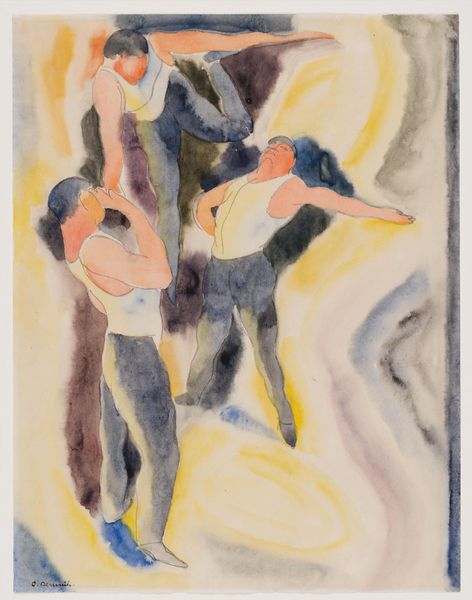

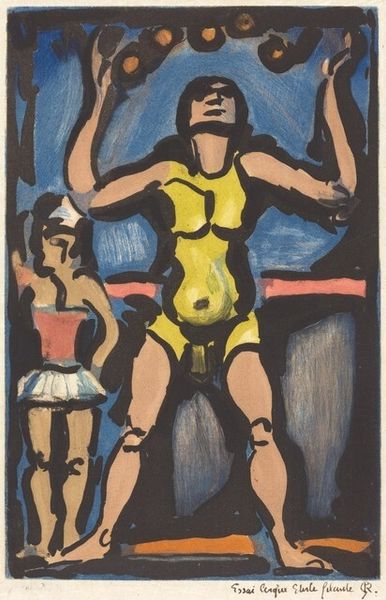

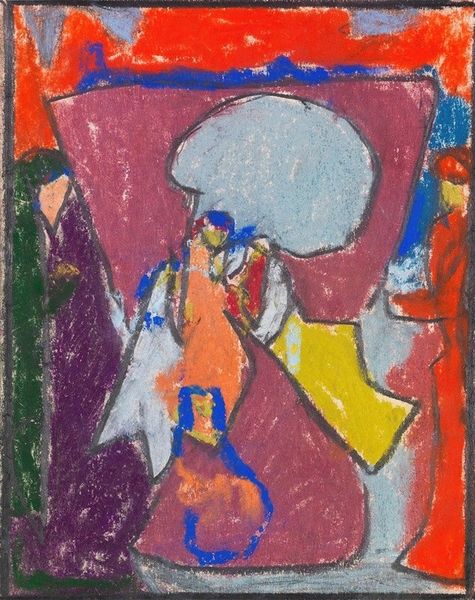

Curator: Here we have Georges Rouault's "Jongleur," a linocut print that’s believed to have been created around 1934. The artist employs bold, somewhat crude lines and blocks of color to depict a performer. What strikes you about this piece at first glance? Editor: There's a certain awkwardness to it, an unfinished quality. The palette is restrained, with these dominant blues setting the mood, yet there's a striking lack of conventional beauty, almost a rawness. It reminds me of figures caught mid-motion on a faded old poster. Curator: Exactly, and it's precisely this tension that resonates with Rouault's broader concerns. The circus and its performers were recurrent motifs, through which he critiques social inequalities. He viewed these marginalized figures as mirroring Christ's suffering. Editor: So, we're encouraged to view the awkwardness as a deliberate commentary, a form of social critique. Thinking about the political landscape of the 1930s, particularly the rise of fascism, do you read the figure’s imposing size as a metaphor for oppressive authority, or perhaps as a critique of performative masculinity? Curator: That's a valid interpretation. The imposing figure could represent the spectacle of power. But looking at it from a different angle, especially regarding class struggle and gender, one can note a contrasting, small figure standing to the left. It looks more conventionally like a female performer or dancer. One may see the size difference as representing the power dynamic inherent within the entertainment world, itself often a metaphor for wider socio-economic disparities. It speaks to who holds visibility, and whose labor goes unnoticed. Editor: I see. The very medium, a relatively humble linocut, lends itself to this message of accessible, almost proletarian art. Unlike refined oil paintings displayed in bourgeois homes, this artwork carries the essence of street performance and its socio-economic setting. What does this specific kind of artistry reveal? Curator: It certainly levels the playing field, democratizing both production and reception of art. Perhaps more than being a simple art object, “Jongleur” represents Rouault's humanitarian perspective, underscoring that empathy can be found in unlikely places. It encourages audiences to think critically about visibility, representation, and human struggles in art. Editor: Thank you. Examining art through this cultural framework makes even its seemingly naive aesthetic decisions feel powerful, pushing viewers to reconsider established canons. Curator: Agreed. And to perhaps confront the roles we unknowingly play in societal spectacles, both in art and life.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.