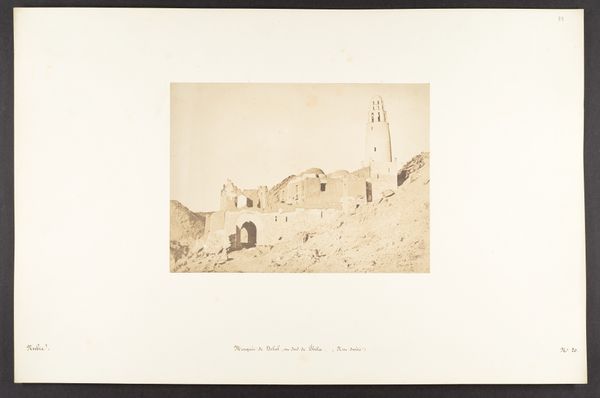

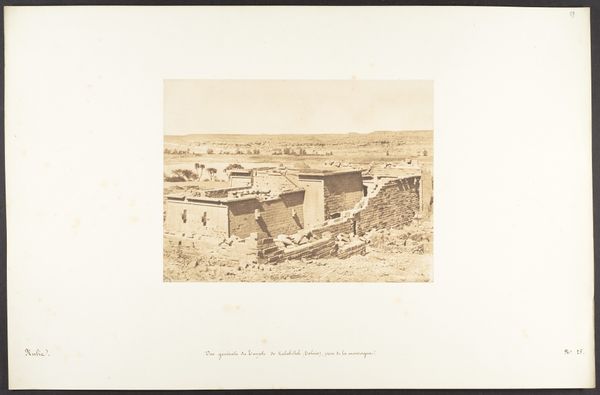

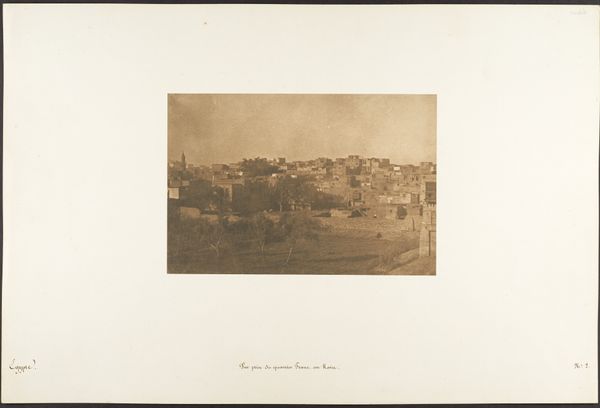

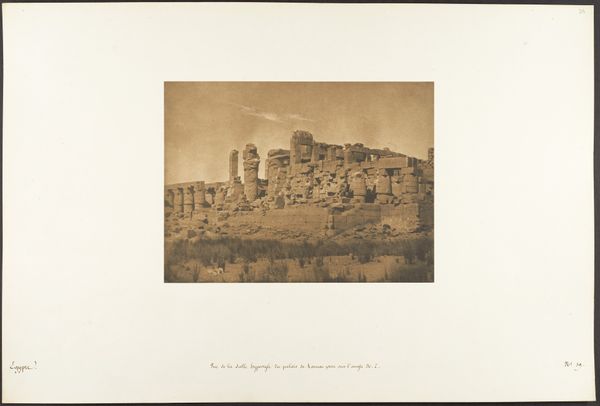

Vue de la Mosquée d'El-Melouyeh et d'un quartier de Jérusalem 1850

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print, architecture

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

cityscape

#

islamic-art

#

architecture

Dimensions: Image: 6 7/16 × 8 1/4 in. (16.4 × 21 cm) Mount: 12 5/16 × 18 11/16 in. (31.2 × 47.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: The sepia tones immediately lend a sense of antiquity and timelessness. There’s a serenity that comes from the muted palette, yet a striking complexity in the composition. Editor: Today, we're observing "Vue de la Mosquée d'El-Melouyeh et d'un quartier de Jérusalem," a gelatin-silver print made circa 1850 by Maxime Du Camp, currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It's an important historical document. Du Camp, travelling with Flaubert, aimed to objectively record these places. But, of course, no record is truly neutral. Curator: I find myself drawn to the domes. The repetition, those subtle variations in size and form, evokes a sense of spiritual geometry—echoes of cosmological harmony in the built environment. Editor: Indeed. Consider the era. The Ottoman Empire held Jerusalem then, yet Western fascination was burgeoning. The "Orient" became a site of projected fantasies and power dynamics, shaping European self-conception through its 'othering'. This photograph partakes in that narrative, intentional or not. Who gets to represent whom, and for what purposes? Curator: Fascinating. Thinking about those Western viewers and their notions about "the Orient," I notice how the photograph seems to reduce a potentially chaotic reality into a structured, understandable composition. This control feels symbolically potent. Editor: Control, power, and visual regimes – crucial points. These images circulated widely, shaping perceptions and solidifying the dominance of a particular viewpoint. And even seemingly objective records always come laden with cultural baggage. The way light is captured, what’s in focus versus what’s not... every choice underscores someone's perspective. Curator: Looking closely now, there is almost an allegorical narrative suggested by light and shadow. The play illuminates the key architectural components, drawing us into those stories rooted in shared cultural spaces and symbols of Islamic faith. Editor: Exactly! So, in observing Du Camp’s work, we reveal much more than just a depiction of Jerusalem. We unpack an era's aspirations, its prejudices, its relationship with the 'exotic,' captured and conveyed via these photochemical techniques. It’s about histories—the city's, the photographer’s, and our own as viewers interpreting a bygone era.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.