![[Trees in Calaveras Grove and Views of Yosemite, California] by Carleton E. Watkins](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzI3Yzk1MjdiLTU5NjAtNGY0OS1iOGEyLTM2ZWIyZjAyYmNmOS8yN2M5NTI3Yi01OTYwLTRmNDktYjhhMi0zNmViMmYwMmJjZjlfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

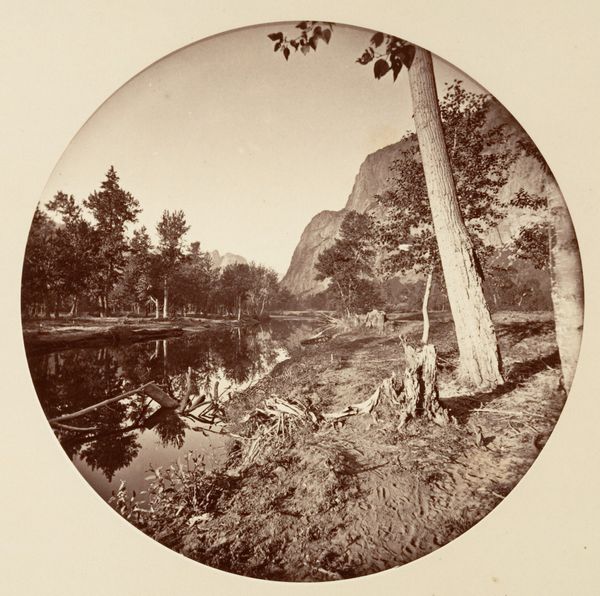

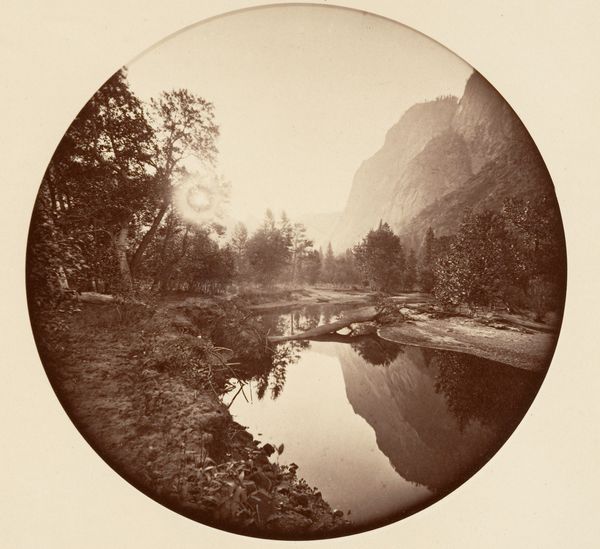

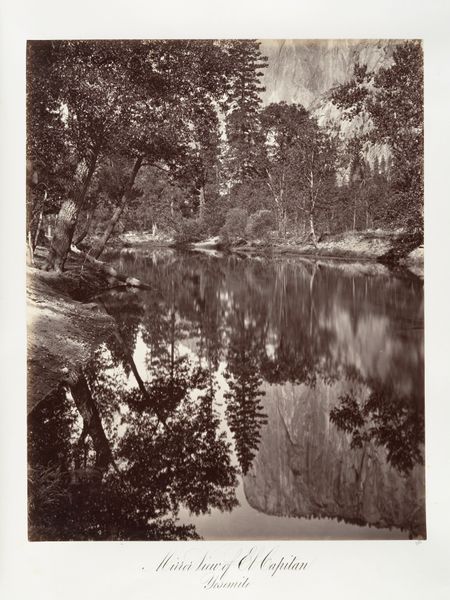

[Trees in Calaveras Grove and Views of Yosemite, California] 1876 - 1880

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: Image: approximately 12.5 x 12.5 cm (4 15/16 x 4 15/16 in.) each Mount: 24 x 25.1 cm (9 7/16 x 9 7/8 in.) each Album: 24.8 x 26 x 3.2 cm (9 3/4 x 10 1/4 x 1 1/4 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: It’s breathtaking how the sepia tones lend this 1876 Carleton Watkins photograph an almost mythic quality. Titled [Trees in Calaveras Grove and Views of Yosemite, California], it is a remarkable work of realism that presents the complex interactions between human settlement and ecological transformation. Editor: The circular frame almost domesticates the monumental landscape, doesn't it? And those trees, in particular, the fallen one in the lower foreground—what's going on there? Curator: Right? They bear witness, and speak to the fraught relationship of the colonial gaze with the land it simultaneously fetishized and despoiled. Yosemite wasn't just untouched wilderness. It was and is a site of Indigenous dispossession. The scale, particularly, feels intentionally crafted to amplify both awe and a claim of possession. Editor: Watkins really gets the scale and the light working together here. What I see at first glance is just the physicality of it all – the minerals in the rocks, the sheer volume of water flowing by. It's less about 'possessing' the view, and more about experiencing the land through its materials, you know? Albumen print technology enabled remarkable clarity here, a clarity that emphasizes the material reality. Curator: That materiality speaks volumes – the resources extracted, the labour of making these large plates, the scientific and commercial imperatives driving westward expansion. It’s deeply implicated in Manifest Destiny. Think about it through the lens of ecofeminism. The act of photographing can be seen as a kind of extraction, one tied to the domination of both nature and women. Editor: I get your point, and you know the history of photographic processes interests me deeply. However, this isn't so simple. In that era photography, especially the albumen print with its dependence on egg whites, engaged deeply with artisanal labor and resourcefulness, too. Think about how Watkins and his crew dragged the cumbersome equipment up the mountain. He turned physical labor into art-making. Curator: That said, I will concede its power. Watkins’s commitment to photography helped spark a real conversation about our place within a landscape often conceived as ‘empty,’ and that led to preservation. But it also reinforced narratives of settler exceptionalism and resource extraction that reverberate today. Editor: Okay, well, seeing his method, the medium's physical grounding, lets me also look beyond that, searching, like, what survives those early extractions—a dialogue with the real, not a domination over it. Curator: Absolutely. Thanks, that changes the view for me too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.