Dimensions: object: 890 x 725 x 140 mm

Copyright: © Catherine Yass | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

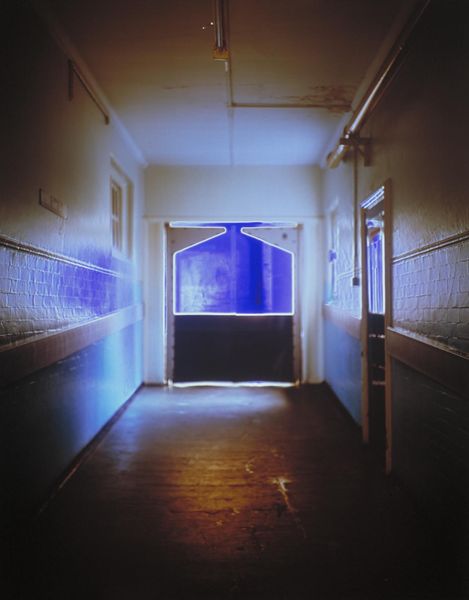

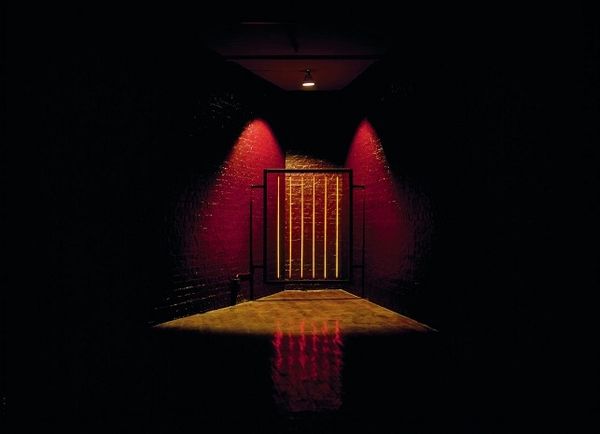

Editor: This intriguing photograph, "Corridors" by Catherine Yass, shows a perspective view of a hallway, playing with disorienting colors. The composition, with its strong central vanishing point, creates a powerful sense of depth. What do you see in this piece formally? Curator: The inverted color palette immediately draws the eye. Note how Yass subverts our expectations, creating a liminal space. The linear perspective converges dramatically, emphasizing the architectural structure. This prompts questions about the nature of space and perception itself. Editor: The inversion definitely changes the mood. I feel like I'm viewing a negative. Curator: Precisely. The artist manipulates form through color, creating a tension between representation and abstraction. Consider how this inversion affects your reading of the space. Editor: It really makes you consider how much color affects perspective. Curator: Indeed. By disrupting the familiar, Yass compels us to examine the intrinsic qualities of form and color.

Comments

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 9 months ago

⋮

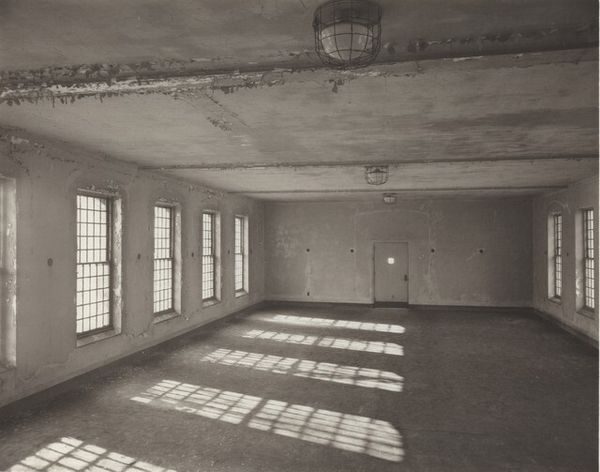

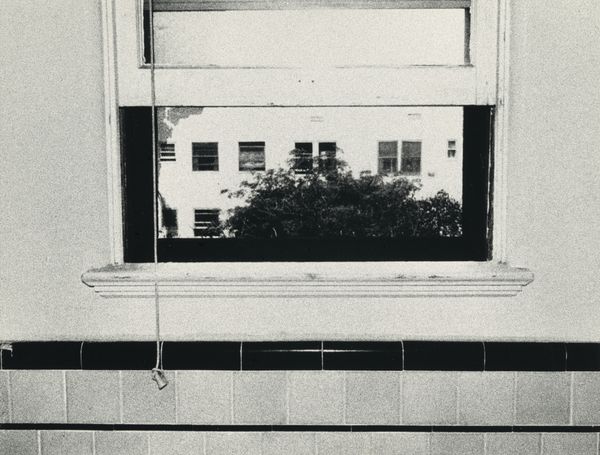

Presented by the Patrons of New Art (Special Purchase Fund) through the Tate Gallery Foundation 1996T07065 Corridors is a series of eight photographic transparencies displayed in light boxes. Featuring mainly luminous blues, greens and yellows as a result of the artist's manipulation of photographic film, they depict interior spaces in a hospital. The photographs are in sharp focus only in the foreground of the image, at the level of the corridor walls, and have been taken with a shallow depth of field. This results in dissolution into more abstracted forms in the areas further away from the camera. In most images this is in the centre, which dissolves into an intense blue glow. Blue light, similar in shade to that of 'Chartres blue', a long-lasting blue stained glass developed in the twelfth century in France for church windows, has become a signature element to Yass's work. Her technique for making images involves taking two photographs of her subject and superimposing them. One is a 'positive' image, the normal form of a photographic image, and the other is a 'negative' image, where light and dark are inverted as on the negative of a photographic print. The photographs are taken within a few seconds of each other. Yass has explained: 'The negative image makes bright areas blue, so bright or transparent areas get blocked by the blue. The final picture is produced by overlaying the positive and blue negative images and printing from that. I think of the space between positive and negative images as a gap.' (Quoted in Adams, p.81.) She has described this gap as 'an empty space left for the viewer to fall into … [resulting in] no limit to prevent the viewer from being pulled right in and being pushed out again.' (Quoted in Adams, p.84.) Yass's first publicly exhibited works, in the early 1990s, were portraits exploring the relationship between the personalities projected and the environments against which they were set. In 1994 she was one of three British artists commissioned by the Public Art Development Trust (a London based charity aiming to promote art and education about art in public spaces) to make a series of images for Springfield Hospital in south west London, a psychiatric institution built in the nineteenth century. She began by looking at photographic research into mental health undertaken at the hospital in the mid-nineteenth century by a local doctor, a Dr Diamond. At that time medical practitioners in the field of mental health were using photography as a tool to classify mental illness according to its physical manifestations. Diamond's portraits of his patients, like those of the famous French neuropathologist and doctor of hysteria, Dr Jean Martin Charcot (1825-93), labelled them under headings of their perceived disability. To subvert this, Yass made six portraits of anonymous hospital inmates and staff without visible indication of their status (whether they were working in the hospital or suffering from 'mental illness'). The photographs used in Corridors were intended as backgrounds to these portraits. Yass became interested in the empty spaces as images in and of themselves, perceiving them as even more disorientating to the viewer without their intended subjects. She uses light boxes to enhance this effect. She has stated: 'The work is not only about the image but also about the light boxes in a physical space. This produces another doubling or turning as the viewer switches between the space of the image and the space they're in. There is a disorientation as they are caught in the gap between them.' (Quoted in Adams, p.87.) The series of eight Corridors was produced in an edition of two, of which this is the first.A further set of four images exists in an edition of four, each of which is unique in its combination. The images each have a subtitle. For this image it is Chaplaincy. Other subtitles are Kitchen (Tate T07066), Daffodil 1 (T07067), Daffodil 2 (T07068), Ash (T07069), Modern Team Base (T07070), Personnel (T07071) and Jubilee (T07072). The images do not have a particular order and may be displayed separately or as a group. Further reading:British Art Show 4, exhibition catalogue, South Bank Centre, London 1995, p.16, reproduced (colour) pp.86-7Parveen Adams, Greg Hilty, Catherine Yass: Works 1994-2000, London 2000, pp.8 and 84, reproduced (colour) pp.19-23, pl.1-8Hospital Projects: Zarina Bhimji, Tania Kovats, Catherine Yass, Public Art Development Trust, London 1995, pp.17-19, reproduced (colour) pp.20-1 Elizabeth ManchesterMarch 2002