Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

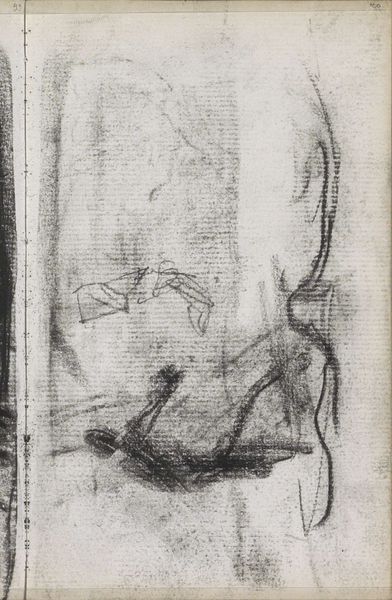

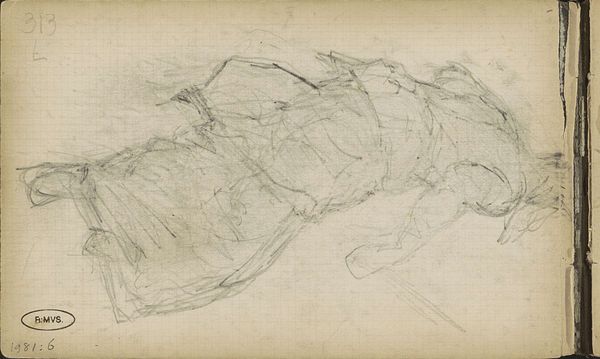

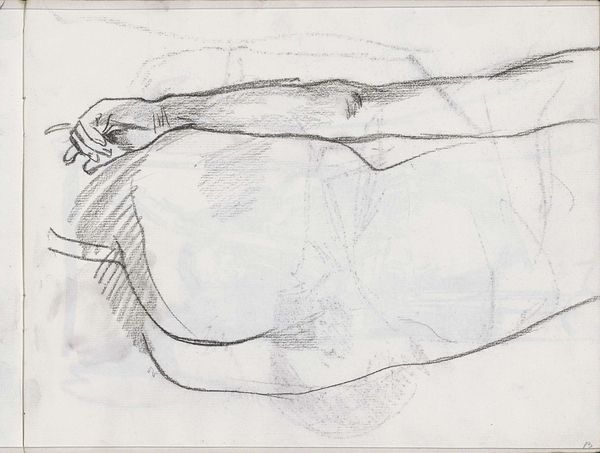

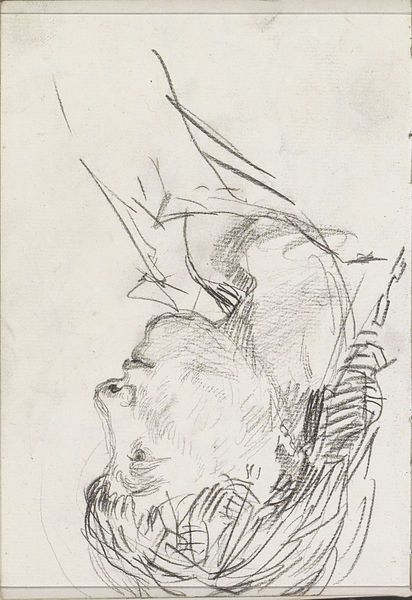

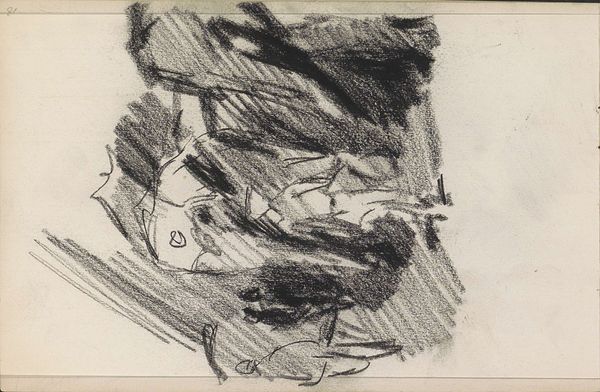

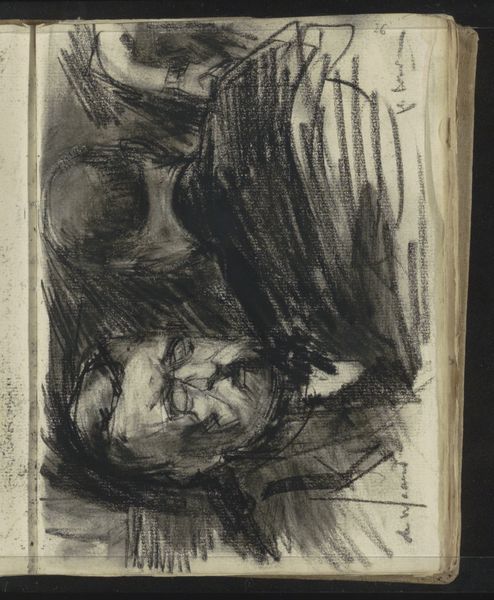

Curator: Here we have Isaac Israels' pencil drawing, "Man in een fauteuil," likely created between 1875 and 1934, now residing here at the Rijksmuseum. My initial impression is of thoughtful contemplation; the figure is so immersed. Editor: It’s gestural, undeniably. You see the haste and the emphasis on form. It strikes me as an exercise in blocking and shadow using very simple tools; the availability and quality of those pencils tell a very different story than marble sculpture, say. What does this mode of relatively casual image making imply about social dynamics? Curator: Indeed, the symbolism lies partially in the everyday scene and medium. A quickly rendered sketch versus a formal portrait. I see it as a snapshot of a moment, attempting to capture the sitter's essence in repose. What do you think the crosshatching might signify to its contemporary audience? Editor: It’s about efficient mark-making, certainly, about value creation using only lines—it’s utilitarian at heart. Look closely, and the composition isn't just aesthetically driven. It hints at a culture embracing new efficiencies in all sectors of life, where capturing a likeness need not entail huge investment in material or artist time. Curator: Yes, that efficiency, even in art, reflects the changing values and faster pace of modern life, absolutely! It speaks to how our ways of thinking shifted due to social contexts and expectations regarding depictions of people and labor. Perhaps even commenting on an evolving artistic purpose overall. Editor: Exactly! So while at first glance it is "simply" a drawing of a man, it opens the door to understand cultural trends, production technologies, the social life of images and more... Curator: A simple sketch it might be, but profoundly suggestive of the cultural milieu of its time, through both technique and subject. It makes me wonder who the model was and his personal significance. Editor: Ultimately it proves that humble tools and methods speak as loudly of history as bronze and oils, so long as one considers how and why things get made, consumed and survive.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.