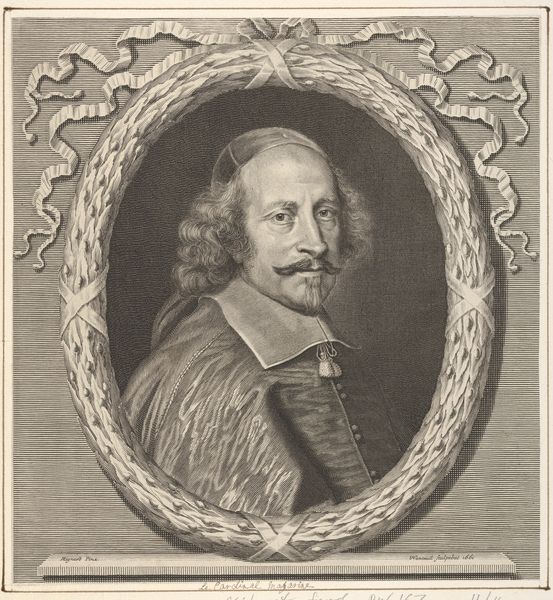

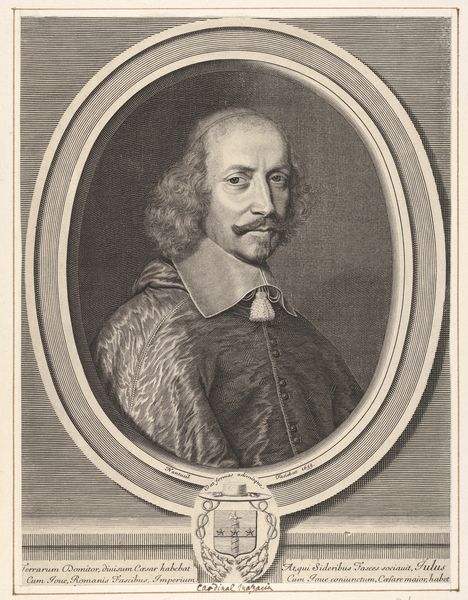

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: This is Robert Nanteuil's engraving of Cardinal Jules Mazarin, created in 1659. The portrait itself feels pretty conventional for the time, but it's framed by this almost wallpaper-like field of stars. What's your take on how the social climate influenced the creation and reception of this piece? Curator: The backdrop is not mere decoration. It directly addresses the politics of image. Mazarin was a deeply unpopular figure, a foreigner wielding immense power in France. Nanteuil, as his appointed portraitist, was tasked with crafting an image, a symbol of authority, that would circulate widely. The stars, think about them – suggesting not just status, but almost a divinely ordained right to rule. Editor: So, the stars are a deliberate effort to rebrand Mazarin's image? Make him seem less like a scheming politician and more like... a celestial leader? Curator: Precisely. Engravings like this weren't just art objects; they were political tools. Think of them as the early modern version of propaganda posters. The printmaking medium also ensured wide dissemination. Who do you think would consume this image and where might it have been displayed? Editor: Maybe wealthy citizens, officials… It’d be in government offices, perhaps private collections of those wanting to show loyalty? It's interesting how the meaning is tied to the social function. Did it work, this star-studded campaign? Curator: History is complex. While Nanteuil produced a technically superb image and the print circulated, resentment towards Mazarin remained. Art can shape perception, but it doesn't exist in a vacuum. It's a reminder that images are active participants in the power dynamics of their time. Editor: I never really considered portraits as propaganda before. Thinking about the intended audience and the political messaging makes it so much more layered.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.