Dimensions: height 198 mm, width 153 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

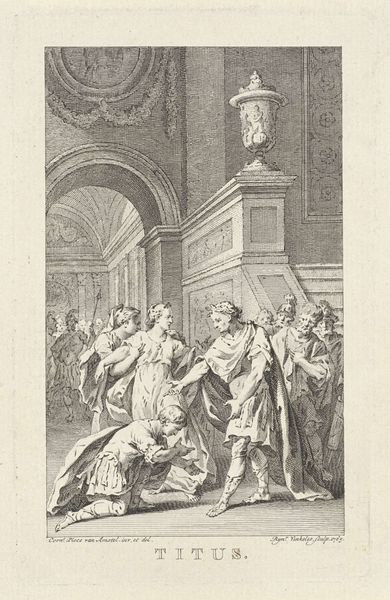

Curator: This print, made by Simon Fokke in 1766, is entitled “Saul laat de priesters en inwoners te Nob doden.” The title, in Dutch, translates to “Saul orders the killing of the priests and inhabitants of Nob.” It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Well, it certainly feels dramatic. There’s a palpable sense of chaos and violence bursting out of what would otherwise be a rather stiff, theatrical composition. What can you tell us about this rather turbulent scene? Curator: It depicts an Old Testament story of King Saul ordering the massacre of the priests of Nob, who had aided David, whom Saul perceived as a threat to his throne. What stands out to me is Fokke's method. The intricate network of engraved lines conveys the emotional turbulence. Notice the density of lines creating dark shadows against the bright highlights on fabrics—see how this texture renders not only form, but the anxiety of the scene. Editor: Absolutely. Beyond the formal qualities, though, the image presents Saul, enthroned under that grandiose canopy, almost as a parody of kingship. The massacre itself, depicted with so much frenetic energy, makes the visual link between earthly power and extreme violence unavoidable. Curator: Indeed. This representation carries quite loaded religious and political symbolism. Kingship here seems less divinely ordained and more derived from physical force and its deployment, right? Nob stands as the counterpoint here, the innocent slaughtered. I wonder about the circulation of prints such as this during the era; what markets were these designed for, and to what end? Editor: Perhaps to remind the public of the ever-present potential for power to corrupt absolutely. It also resonates on a psychological level; the image forces one to confront the darker aspects of human nature and the dangers of unchecked authority. The contrast in Fokke’s rendering almost serves to clarify the spiritual dangers implicit within violence like this. Curator: It really emphasizes how the selection of technique impacts how stories are told, especially since engraving, as a mass-producible medium, was much more available for circulation in 18th-century markets. Editor: Right, and as viewers, we are left contemplating the uncomfortable connections between history, power, and our own humanity. It feels just as potent today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.