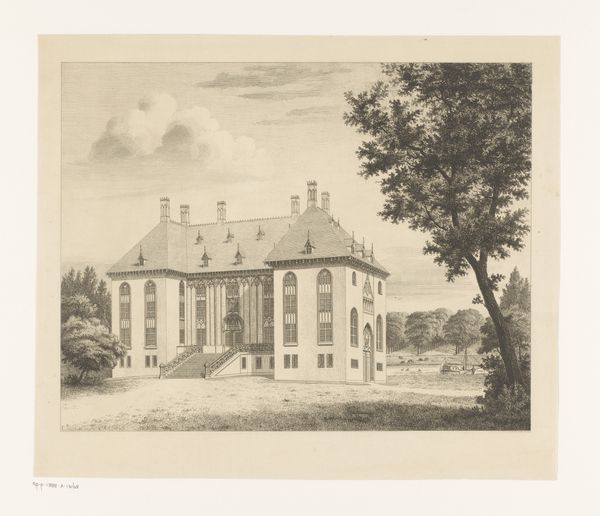

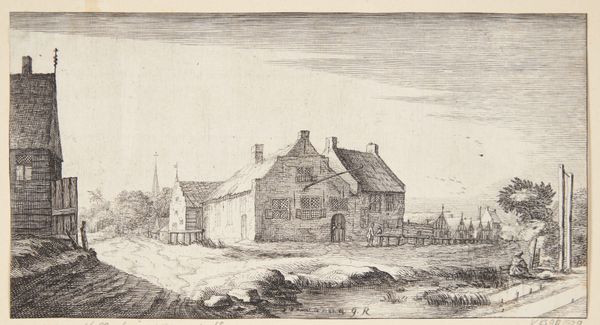

drawing, print, etching, paper, pen, architecture

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

paper

#

pen

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 151 mm, width 240 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: It's rather charming, isn’t it? A scene so still, almost ghostly. What's your take on it? Editor: Ghostly indeed. The symmetry, the subdued palette – it’s all very proper, very Dutch Golden Age. Let's dive in, shall we? We're looking at "Het Huis te Kessel bij 's Hertogenbosch," which translates to "The House at Kessel near 's-Hertogenbosch," by Abraham Rademaker. It's dated somewhere between 1685 and 1735, held here at the Rijksmuseum. An etching, pen and paper, if I’m not mistaken. Curator: It really is the etching that lends it this uncanny feel. That distant windmill... there is a sense of time standing completely still. I mean, think of the people who lived in this house. All gone now. Does the architecture speak to you? The ratios seem slightly off, almost childlike in its rendering. Editor: Well, the house is depicted frontally, and that's a strong compositional choice. It anchors the entire scene. We have this play with horizontals: the land, the roof lines, contrasting nicely with the verticals of the trees, and of course, the house itself. And that balance gives a certain monumentality. Curator: Monumental melancholy, I’d say. Rademaker captured more than just a house, didn’t he? It’s a meditation on history. What do you think somebody wanted of this house for it to be drawn? Editor: Functionally, perhaps to document it as a sort of architectural record, but artistically, Rademaker uses the subtle textures achievable through etching to give this image depth, transforming a mere building into a subject worthy of aesthetic consideration, of symbolic weight. Curator: There’s something truly wonderful about the quiet intensity Rademaker brings to what is essentially just a house. It becomes less about what’s seen and more about what is felt – like memory distilled into lines on paper. Editor: Precisely. It’s the skillful manipulation of line and form elevating the mundane. It prompts us to contemplate what it means to inscribe meaning through art, not just for Rademaker, but for us as viewers, as well.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.