drawing, paper, engraving, architecture

#

shading

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

sketched

#

old engraving style

#

paper

#

historical fashion

#

desaturated colour

#

geometric

#

line

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

#

architecture

#

columned text

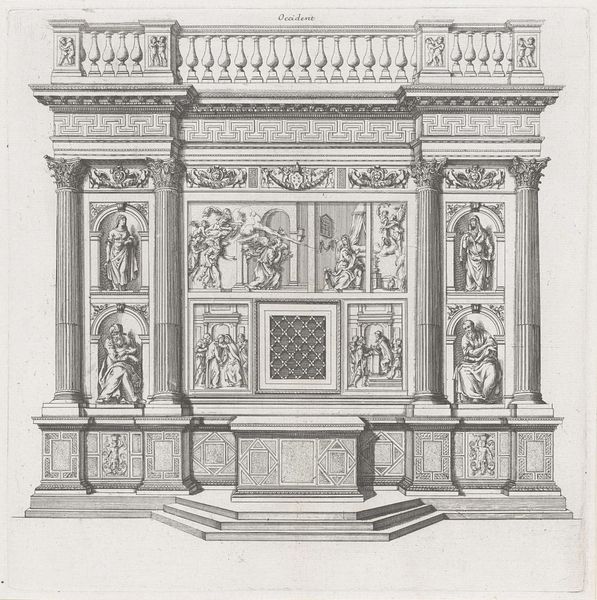

Dimensions: height 270 mm, width 245 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

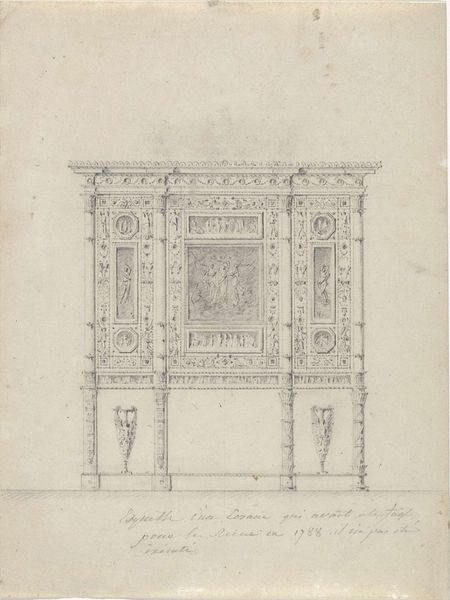

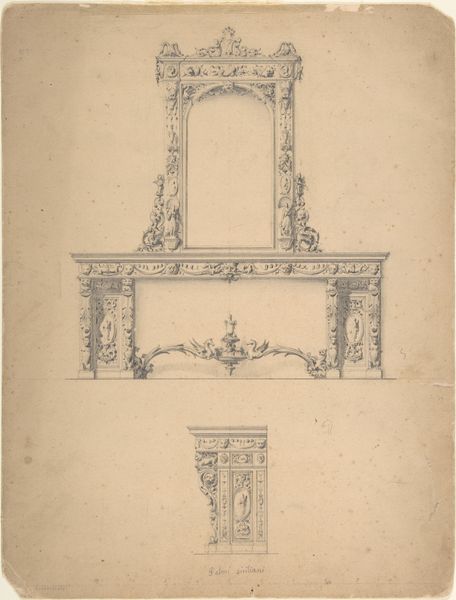

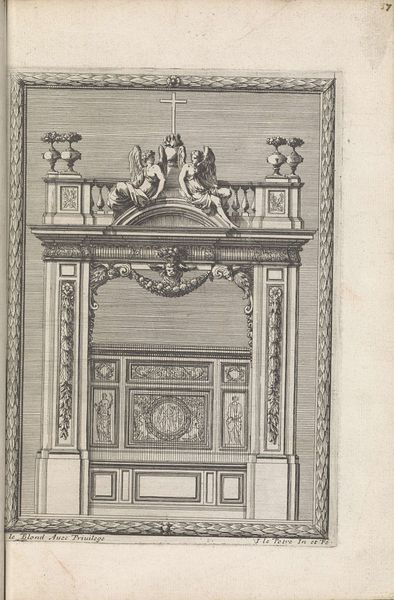

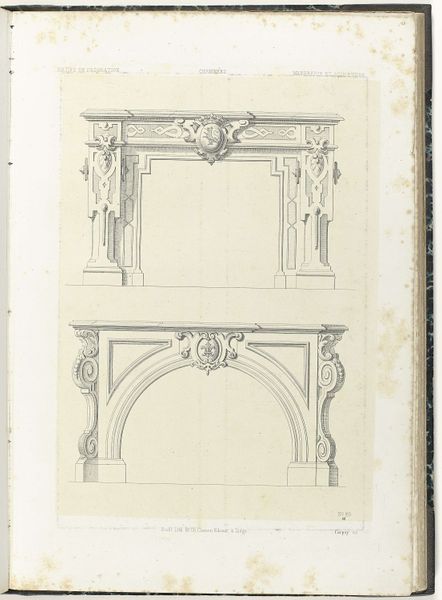

Curator: Here we have "Vier schoorsteenmantels," or "Four Chimneypieces," an engraving dating to 1776, by Placido Columbani. It's held here at the Rijksmuseum. What are your first impressions? Editor: I find it austere. The delicate lines of the engraving coupled with the subject matter creates a very formal feeling, like a blueprint for privilege. Curator: Indeed, Columbani was known for his decorative arts designs. He significantly influenced Neoclassical style in Britain. Thinking about social context, chimneypieces during this period were statements of wealth and taste, especially among the burgeoning middle class. Editor: Precisely. And note how each design is distinct, a hierarchy within the image itself! The bottom one is perhaps the most visually busy with those mythical beasts, drawing the eye, reinforcing the idea that design was integral to social posturing. Curator: Right, it's almost like a catalog of aspirational fireplace designs. These designs reflect not only classical influence, of course, but also emerging social hierarchies. They performed important functions within domestic spaces and architectural display. Editor: And the gendered aspects are undeniable. Public spaces like libraries or drawing rooms might showcase designs like this, subtly suggesting an ideal family with both wealth and 'proper' taste. There's such a pressure for women especially. How does the materiality speak to you? Curator: The fine lines and tonal variations in the engraving certainly lend it an air of sophistication and permanence, appropriate to the elite associations you bring up. It has this interesting sense of precision but then printed on something like aged paper, as if meant for future reference but not necessarily widespread use, something bespoke even in its distribution. Editor: I agree. It's less about mass production and more about exclusive circulation amongst a certain societal circle. The paper itself acquires a sort of archive, whispering tales of commissions, artisans and client expectations. I keep thinking about those artisans of colour who would rarely get recognized. Curator: An important point! And that labour, of course, remained largely invisible even while facilitating the cultural capital being accrued in those drawing rooms. These designs acted as material culture, not just expressions of artistic merit. I will carry the memory of them back in context, as markers of privilege with unspoken labour behind them. Editor: It all echoes throughout those silences of art history and social inequity. Next piece, maybe, we will discuss something in conversation with those perspectives and ask these same, hard, very important questions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.