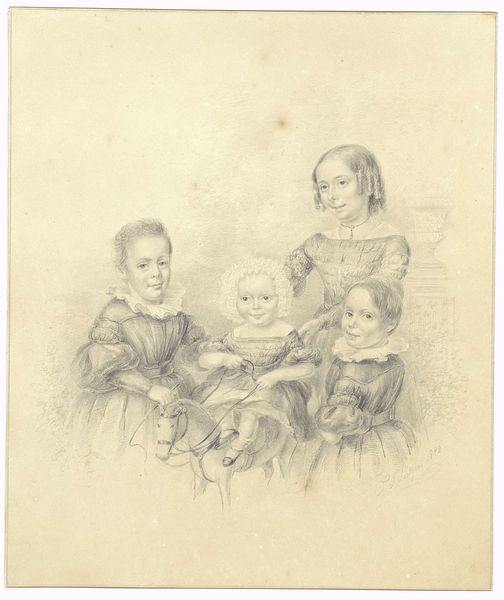

drawing, pencil

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

pencil work

#

realism

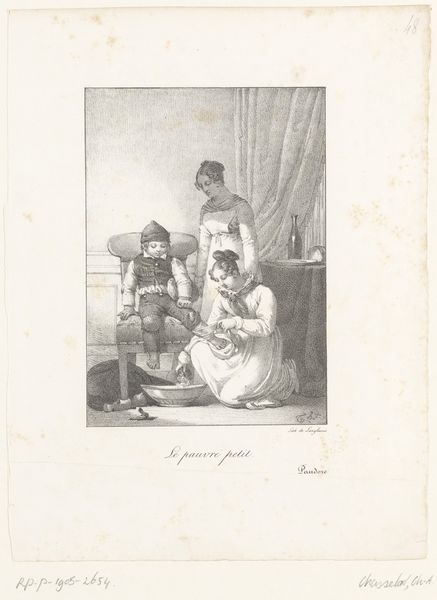

Dimensions: height 505 mm, width 380 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

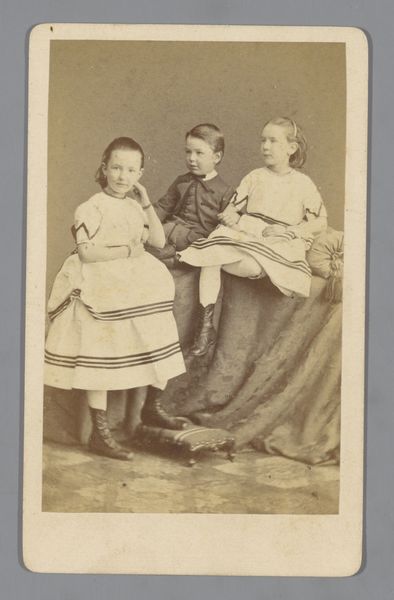

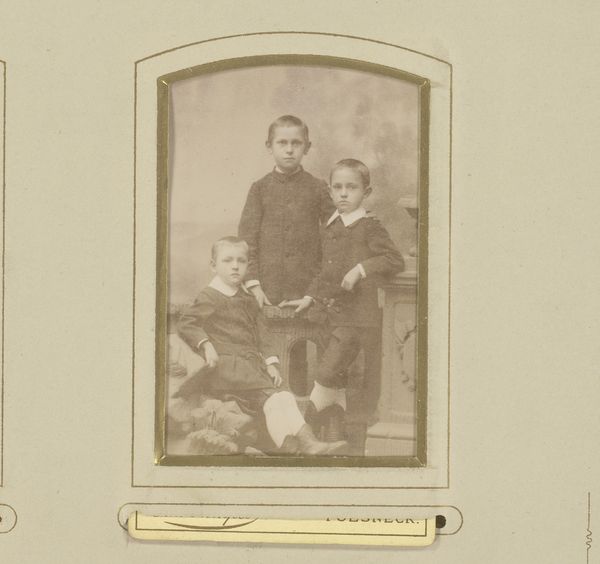

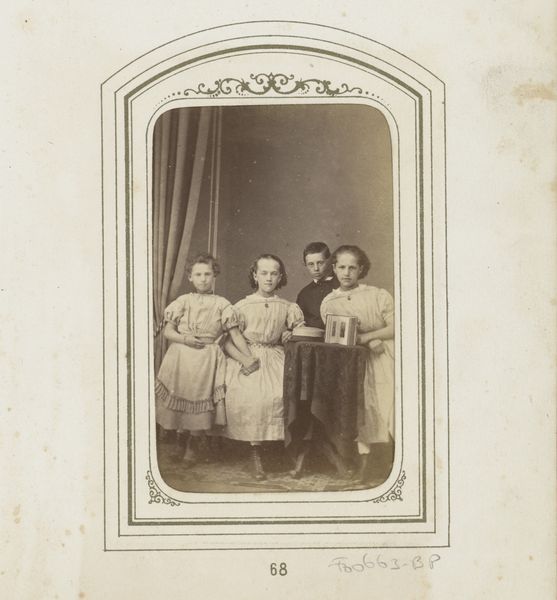

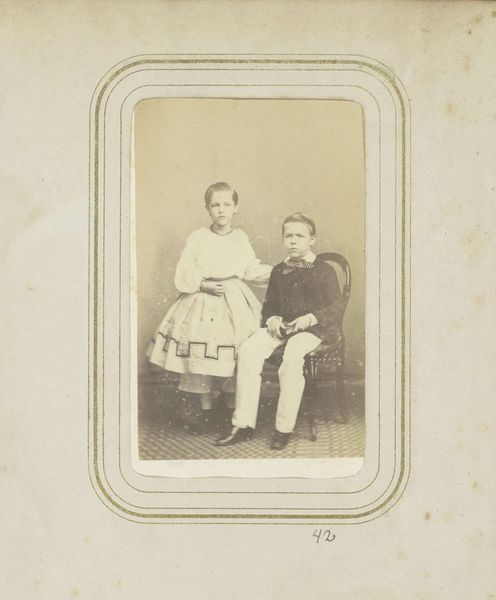

Curator: We're looking at a drawing here titled "Portret van drie kinderen Van Rappard", which translates to "Portrait of three children Van Rappard," attributed to Johan Hendrik Hoffmeister, created sometime between 1851 and 1883. Editor: My first impression is one of reserved composure; they have an almost melancholy seriousness. And what precise, delicate pencil work. Curator: Yes, the light pencil work certainly lends a somber tone, but also provides a soft and precise medium. Consider the Victorian era, the meticulous process required to capture likeness before photography became widespread. Editor: Precisely, it speaks to the cultural moment. Beyond portraiture, though, consider the subtle sartorial symbols –the sash, the carefully rendered garments. Notice how they hint at family identity and perhaps aspiration? Curator: Absolutely. These aren’t just depictions of children, but rather social signifiers, subtly embedded within the seemingly straightforward family portrait. You can almost feel the weight of societal expectations. Think about access to such a personal, private moment for posterity. Editor: And it speaks to the children’s own position within their familial narrative, a position of assumed innocence. That is how they wish to present themselves to their descendants, with this image acting as a powerful relic that will be kept within the Van Rappard lineage. Curator: Good point. It also begs the question: Who was it commissioned by and why? Perhaps they hoped to visually project a legacy through the very specific and very crafted, means of production with its limited accessibility. Editor: In that way, we see more than a family picture, and we begin to see a historical marker; that is to say, it transcends a portrait, and almost feels like a heraldic shield in graphite and paper, and, in its way, carries the same intent and purpose. Curator: I think that is spot on, each carefully crafted line builds this facade of Victorian family life, but ultimately, is simply a material expression of the complex social and economic landscape. Editor: Yes. Leaving us to look beyond technique, style, and pencil and to observe how meaning can exist on multiple visual plains across both eras: Victorian and our own.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.