paper, photography

#

portrait

#

paper

#

photography

#

historical photography

Dimensions: height 90 mm, width 57 mm, height 102 mm, width 62 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

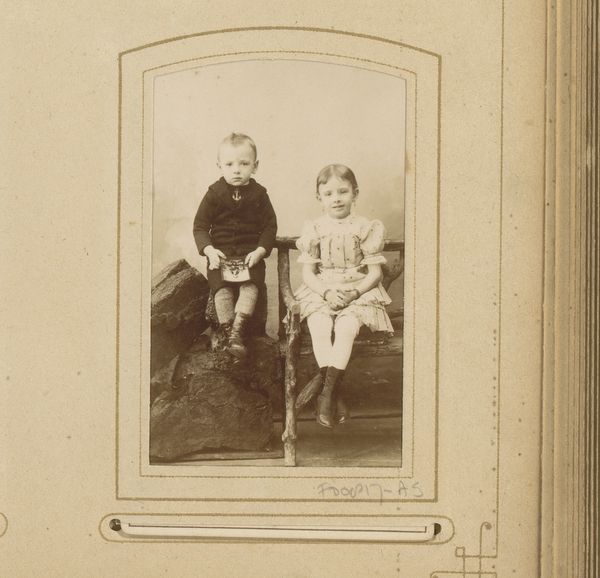

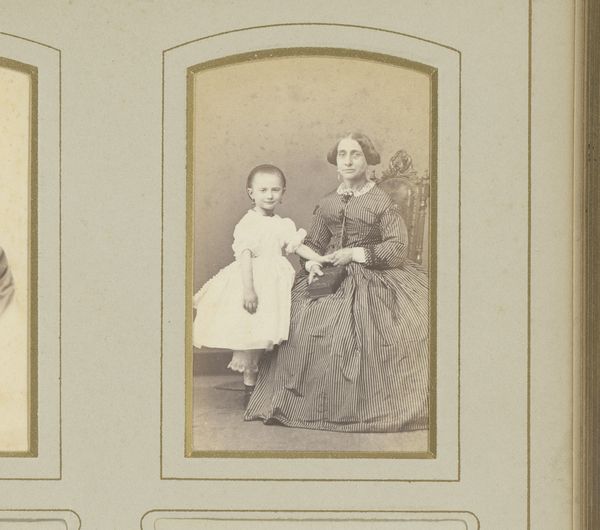

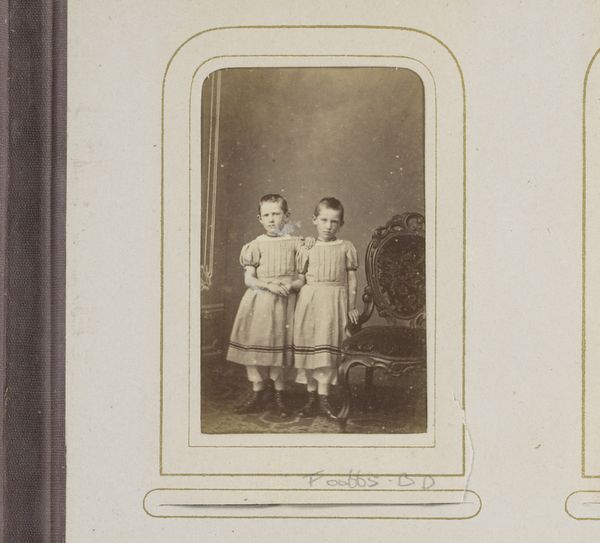

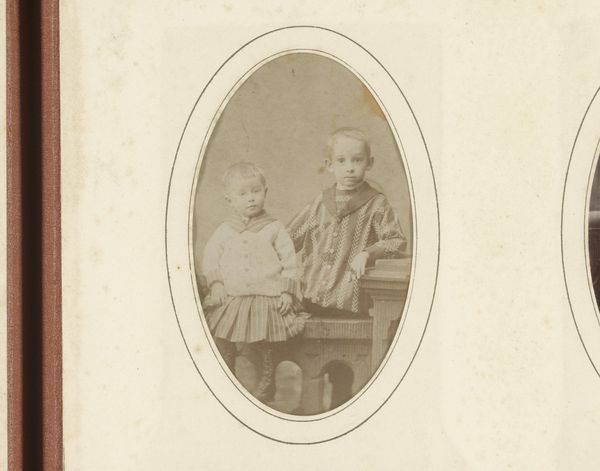

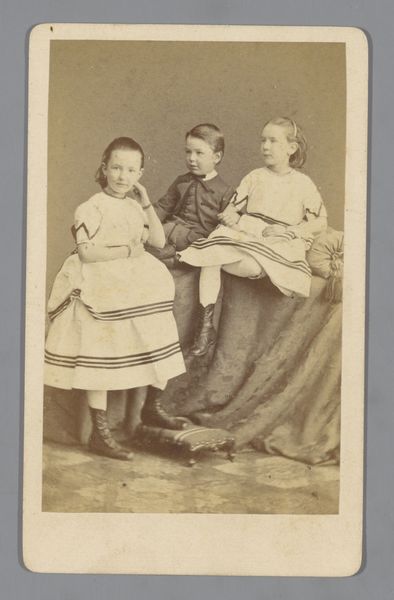

Curator: Here we have "Portret van een jongen en een meisje," a photograph dating from approximately 1857 to 1880, created by Woodbury & Page. The work is mounted on paper. Editor: It's fascinating how photography captures a certain social melancholy, isn't it? These children exude a quiet dignity, a sort of enforced stoicism. Curator: Absolutely. Considering Woodbury & Page's studio, it's worth noting their prominence in commercial photography in the Dutch East Indies. This likely wasn't just an artistic endeavor but part of a wider, industrialized image production. I'm drawn to the materiality—the albumen print on paper, the very chemical processes that rendered these subjects permanent. Editor: The staging also tells a story. His posture suggests privilege, and his clothes hint at a certain class standing within the colonial hierarchy of that time. It speaks volumes about societal expectations and gender roles during the period of Dutch colonialism. How does the technology of the image intersect with social realities? Curator: Precisely! The collodion process used to make the image required particular knowledge and tools. Access to photography in this era also highlights the divide between those who could afford to be depicted and those largely excluded. This makes you think, who was producing it and who was able to pay for it? Editor: And within that controlled environment of a studio, what power dynamics were at play? Children, particularly those whose likenesses might perpetuate colonial ideologies, became subject to the photographic gaze and therefore also to historical narratives being constructed about them. Curator: This piece really brings up questions of labor, of access, and of how early photography impacted trade between the Netherlands and Dutch East Indies, not only as images circulated but in equipment, skills, and capital exchange as well. Editor: The implications are so extensive, a reminder that even seemingly simple images carry the weight of colonial past. Curator: True—thinking of its lasting, concrete evidence. Editor: Ultimately, a tangible archive that resonates powerfully in the present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.