print, etching, architecture

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

italian-renaissance

#

italy

#

architecture

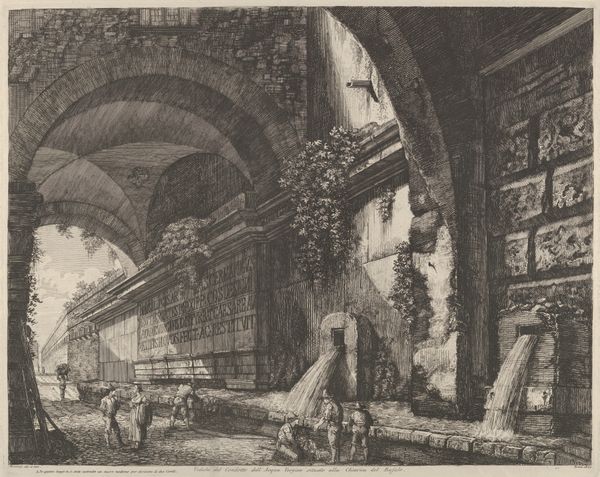

Dimensions: 16 5/16 x 21 5/16 in. (41.43 x 54.13 cm) (plate)

Copyright: Public Domain

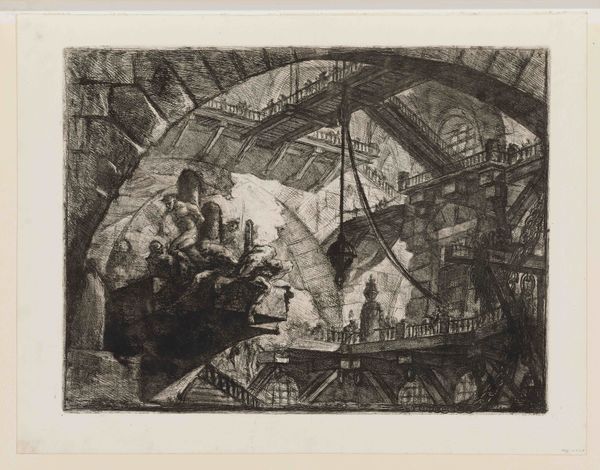

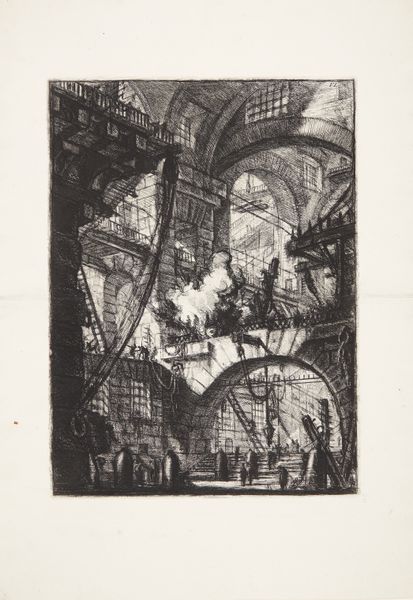

Giovanni Battista Piranesi created this etching, "The Sawhorse," revealing the emotional weight carried in images across time. The sawhorse itself, prominently placed, is more than a mere construction tool; it symbolizes labor, building, and perhaps, reconstruction. These motifs of construction and ruin resonate deeply within us; think of the Tower of Babel, an eternal symbol of human ambition meeting inevitable decay, forever imprinted in our collective consciousness. Consider, too, how such images tap into our own psyches, the recurring dreams of building or the anxiety of collapse, mirroring our deepest fears and aspirations. The sawhorse, then, becomes a potent symbol, engaging us on a subconscious level. It transcends its immediate context. A reminder that symbols continuously resurface, evolving and taking on new meanings throughout history, embodying the cyclical nature of human experience.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

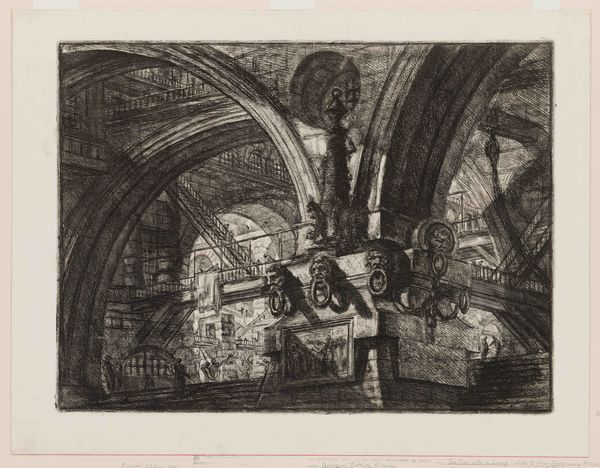

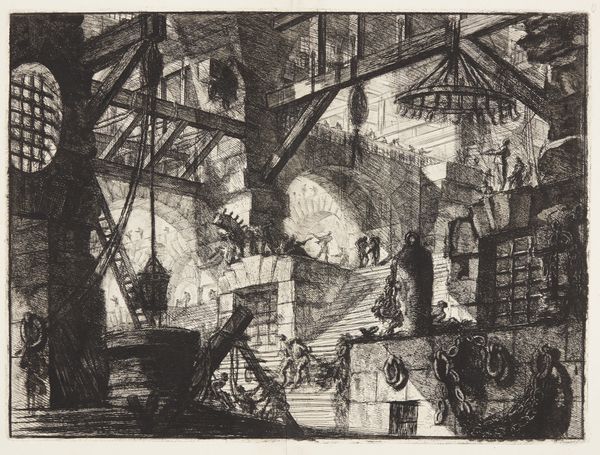

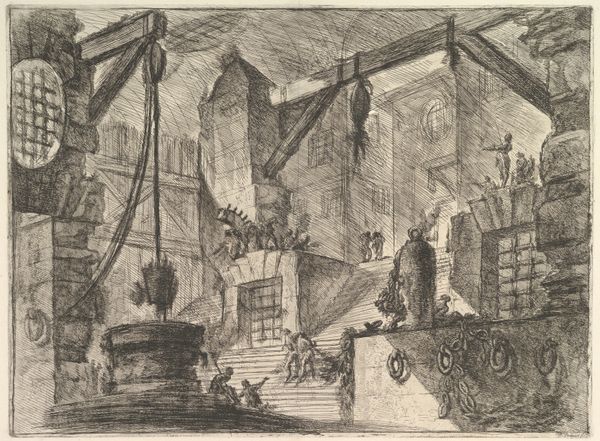

The timeless, gloomy Prisons are entirely man-made. Hewn from stone and timber and fitted out with rope and iron, they exclude the outside world. Not even time exerts its influence here. In Clarel, the longest American poem, Herman Melville captures the impression that the Prisons made on Romantic artists: In Piranesi’s rarer prints,Interiors measurelessly strange,Where the distrustful thought may rangeMisgiving still—what mean the hints'Stairs upon stairs which dim ascendIn series from plunged Bastilles drear—Pit under pit; long tier on tierOf shadowed galleries which impendOver cloisters, cloisters without end;The height, the depth—the far, the near;Ring-bolts to pillars in vaulted lanes,And dragging Rhadamanthine* chains;These less of wizard influence lendThan some allusive chambers closed. bastilles (n.) fortress prisons*rhadamanthine (adj.) hellishly severe These two etchings were printed from the same copper plate. As a young man Piranesi had emphasized his freedom of invention with rapid, slashing strokes and airy spaces, but twelve years later, his sensibility had changed. His experience making dozens of large, intricately detailed etchings of ancient and modern structures profoundly deepened his understanding of Rome’s architectural fabric. The clarity and concrete presence of these studies outstripped all others until the invention of photography (see illustration). In rethinking the Prisons, he applied the methods of shading and delineation that he had learned in his documentary work to increase the materiality of his fictive architecture, such as the towering mass at the left or the complex structure in the middle distance.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.