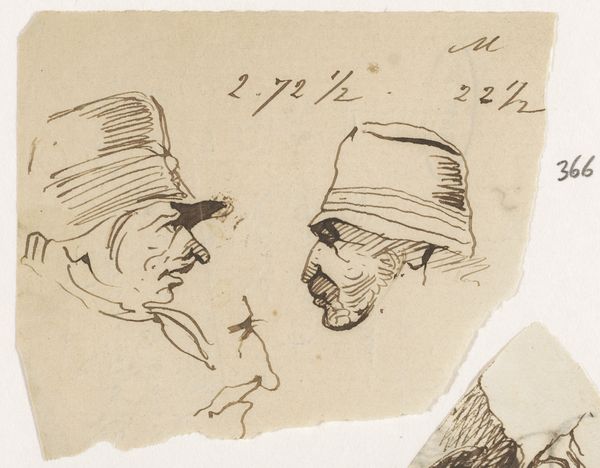

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 144 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

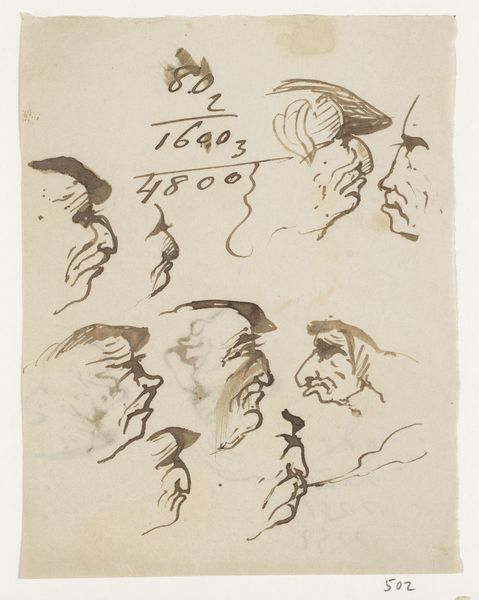

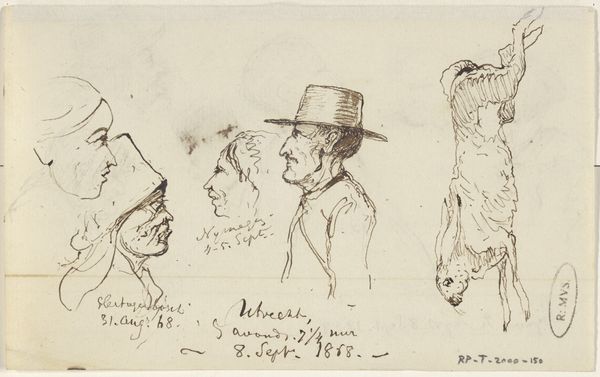

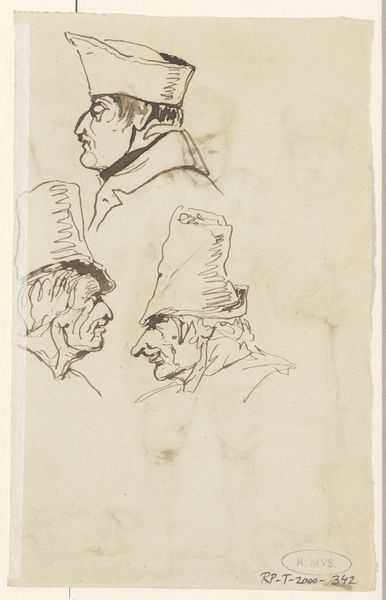

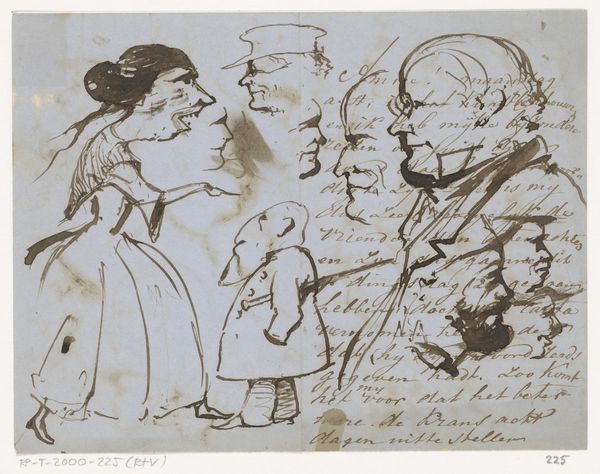

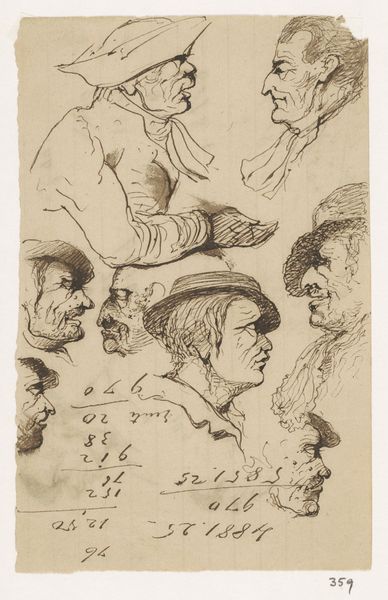

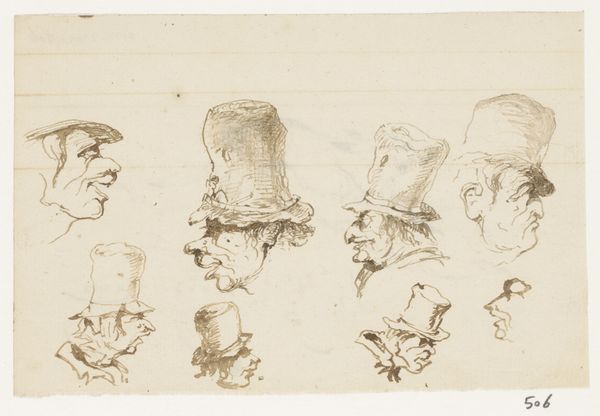

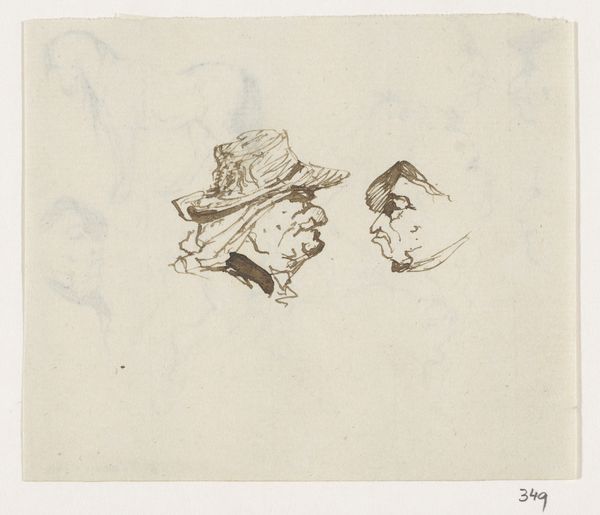

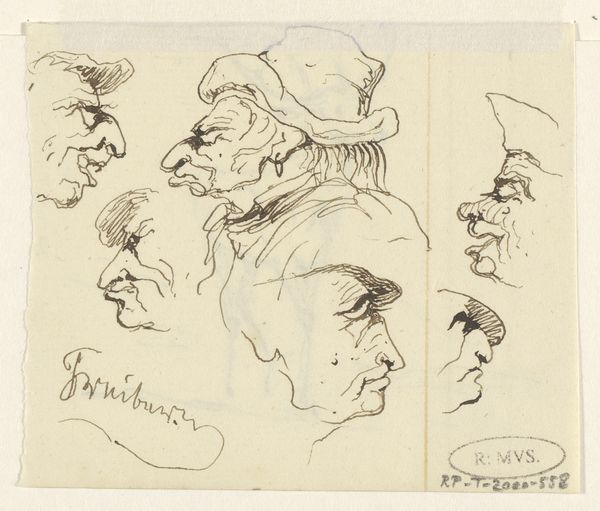

Curator: This drawing, aptly titled "Koppen" – which translates to "Heads" – by Johannes Tavenraat, likely dates between 1840 and 1880. Executed in pen and ink, it offers an intriguing study of various male head profiles. Editor: It's striking how each head possesses a distinct character despite the minimalist technique. There’s a rawness, a sense of immediate observation captured by the sharp contrast of dark ink on the pale paper. It feels surprisingly modern, doesn't it? Curator: Absolutely. But let's contextualize that “modern” feel. Tavenraat was working in an era wrestling with evolving societal roles and burgeoning national identities. This sheet of studies reminds us how physiognomy and caricature became tools to visualize and enforce social biases through these portrait sketches. Note how each of these “Koppen” wears different head covering; each hat functions as a socio-economic signifier that tells us the perceived class of each “Kop”. Editor: I see what you mean. It's not merely a study of form but also of social roles visualized. Still, there’s a delight in the linework itself. The varying densities of the crosshatching, the confident strokes, the rabbit, all adds levity to what might otherwise be purely academic. Curator: Exactly. Tavenraat creates a space to confront prevailing notions around who matters and why. It challenges us to investigate the historical roots of our social structures while contemplating their current echoes in modern cultural representation. It is even more intriguing if we imagine him creating such sketches during public events; a political gathering perhaps? Editor: Regardless, there's a real tension created. Tavenraat’s "Koppen," beyond being an exercise in skill, speaks volumes about the historical baggage and social codes embedded within even the simplest representation of the human face. It's deceptively complex. Curator: Yes, and examining such sketches can encourage awareness of present social inequities regarding power and representation within social contexts. Editor: In the end, I suppose Tavenraat nudges us toward examining our own prejudices while recognizing that aesthetics are never truly neutral.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.