drawing, paper, ink, pen

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

self-portrait

#

quirky sketch

#

pen sketch

#

figuration

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

sketchwork

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

watercolour illustration

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

academic-art

#

sketchbook art

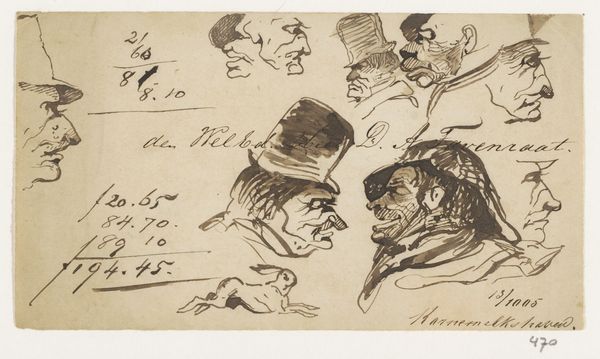

Dimensions: height 92 mm, width 115 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Schetsblad Kleef 1843," a fascinating sketch sheet created in 1843 by Johannes Tavenraat, housed here at the Rijksmuseum. It's ink on paper, featuring studies of faces and a figure holding what appears to be a rifle. Editor: My initial reaction is one of intrigue. The figures, rendered so swiftly in ink, possess a certain intensity. There’s an almost restless energy about the composition, a feeling that these were fleeting observations quickly captured. Curator: Precisely! These rapid sketches allow us a glimpse into Tavenraat's artistic process. The clustered heads—almost caricatures—echo familiar motifs found in much older Northern European art, recalling, for instance, the grotesque heads explored by Leonardo or Bosch. It also reveals something of his intellectual formation, given he clearly places himself within the existing canon. Editor: Yes, but even in his imitation he captures a cultural moment—a Dutch Golden Age revisited within a newly configured kingdom following the Napoleonic era. Note how, along with the rapidly sketched portraits, Tavenraat has also penned observations about hunting—the rifle. Hunting culture had obvious class associations: to what extent did artists have to align themselves to elite social practice in order to flourish? Curator: Absolutely, and we see the figure with the rifle front and centre on the page, a commanding pose next to rapidly drawn heads that may depict Cleve residents. Furthermore, the hunt carries potent symbolic weight. As far back as ancient Greek and Roman iconography, the hunt often symbolized social cohesion but, no less frequently, savage dominance of nature. In a society that now grappled with environmental conservation in light of post-Napoleonic industrialization, it’s fascinating to consider what the hunting image invokes at this time. Editor: These symbols and sketches become historical touchstones, provoking questions about identity, class, and the changing Dutch landscape during the 19th century. What stories of economic or social disparity might these faces tell, particularly given Tavenraat has captioned, with wry honesty, “I think it is something other.” Curator: "Something other," indeed. He hints at more complex layers of reality lying beneath the surface of this simple drawing. Editor: And with that quick phrase, Tavenraat seems to be calling to us from 1843 to continue posing new questions from this work.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.