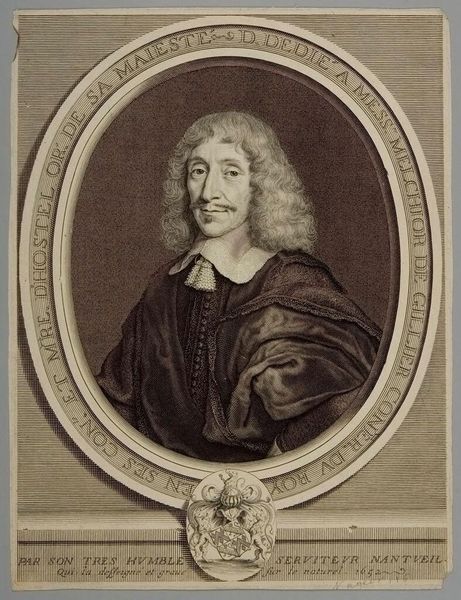

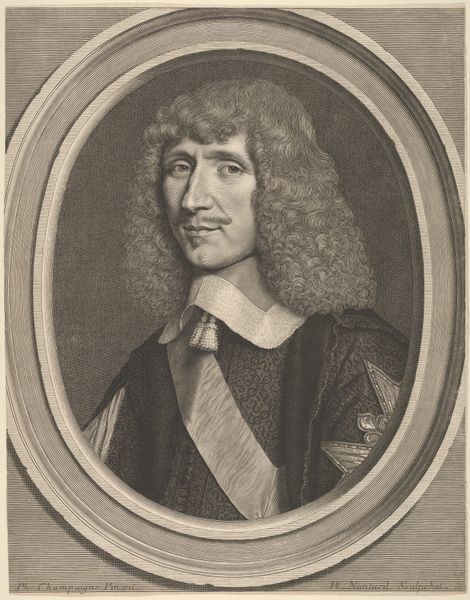

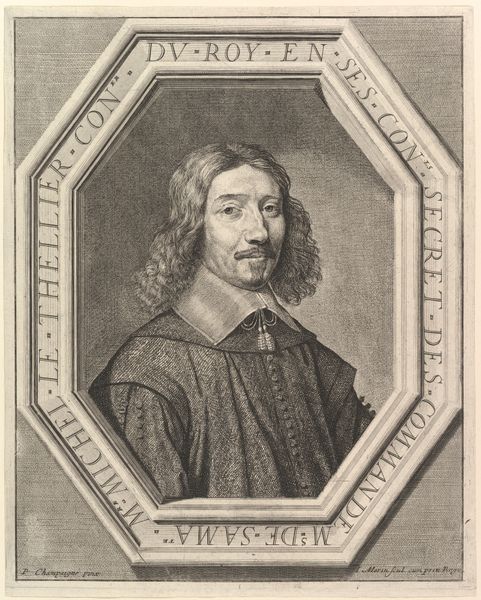

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

men

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 12 1/16 × 9 1/8 in. (30.7 × 23.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have Robert Nanteuil’s 1652 engraving of Melchior de Gillier. The work resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It has an air of somberness, doesn’t it? The stark monochrome, the man's composed expression—it’s visually very controlled. A closed circle containing all the imagery only opens when a very rigid base completes it on the very bottom of the piece. Curator: Engravings like this were a crucial form of information dissemination in the 17th century. Nanteuil, celebrated for his skill, was essentially mass-producing images of important figures like de Gillier. The process itself—the labor of cutting those lines into a metal plate—speaks volumes about the effort involved in circulating these likenesses, almost a celebrity snapshot of the era. And note the text surrounding the figure itself! An open proclamation of service on behalf of the engraver towards their high born subject Editor: Precisely! It’s about structure as much as reproduction. Look at the precision in those lines, how they create form and shadow. The circular frame and ornate lettering provide a geometric counterpoint to the curves of his hair and robe. It's a very baroque composition—complex, but ultimately balanced, with an obvious interest on social structures within its layout, almost making the central figure subservient to a text, the contract, or in this case an address to "Sa Majesté" translated loosely to "His Majesty", as we can read at the top, encircling the whole visual! Curator: And consider the social context. De Gillier was "DHŌSTEL OR DE," as the frame tells us: likely a high-ranking state official under the king. This engraving served to broadcast his image and solidify his position within the social hierarchy. The material—the print—becomes a tool of power. Who knows the reasons why Nanteuil found himself having to craft it so beautifully and so masterfully for "natural 1652." as proclaimed by his signature. It's possible he was paid well for his labor... Editor: A tool, certainly, but also an aesthetic object in itself! Think about how the texture of the paper interacts with the ink, the light playing across the surface. Nanteuil has a clear understanding of visual rhetoric. Curator: A clear understanding shaped by patronage and the economic realities of his time. I keep returning to the sheer labor involved in creating something like this. It connects the artist to a whole network of workshops, suppliers, distributors... Editor: An important network, and it all funnels to what meets the eye today. Every line, tone, composition, all coming from a single choice: what is the message? and is it coming across? Curator: Absolutely, an eye catching display and a clear intent... A perfect testament to labor's place within our understanding of the artworks that survive it. Editor: Quite. And as always, the convergence of aesthetic intent and skilled production crafts such enduring objects!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.