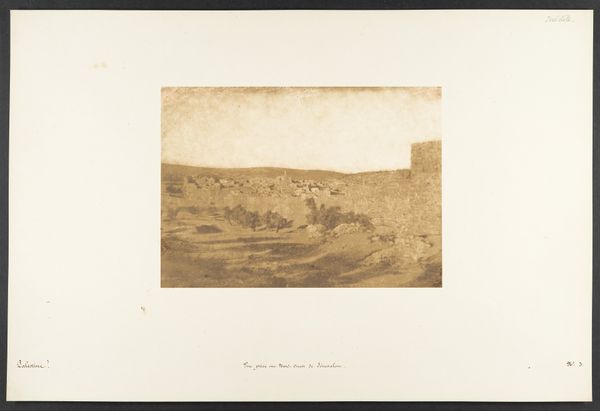

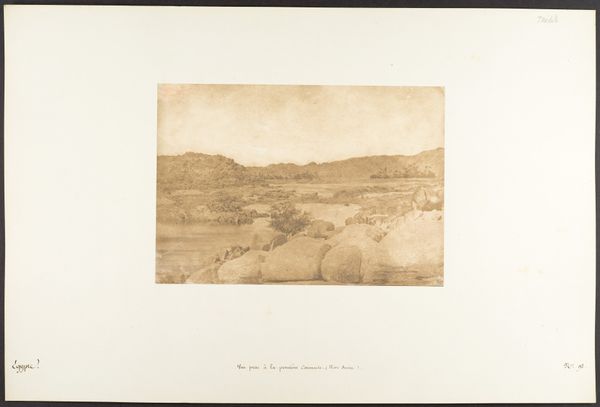

Vue prise au Village d'Abou-hor (Tropique du Cancer) 1850

0:00

0:00

daguerreotype, photography, architecture

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

orientalism

#

architecture

Dimensions: Image: 6 1/16 × 8 13/16 in. (15.4 × 22.4 cm) Image: 8 7/8 × 6 9/16 in. (22.5 × 16.7 cm) Mount: 18 11/16 × 12 5/16 in. (47.5 × 31.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This daguerreotype, "Vue prise au Village d'Abou-hor (Tropique du Cancer)," was captured by Maxime Du Camp around 1850. There’s a stillness to it, almost melancholic, emphasizing the ruinous architecture and harsh landscape. How do you interpret the cultural symbols at play here? Curator: The weight of antiquity presses down, doesn't it? Consider the symbolic resonance of photographing ancient Egypt using this new technology. The daguerreotype, itself a groundbreaking invention, attempts to capture something eternal, almost immutable, yet the scene betrays the relentless passage of time through decay and ruin. The Orient was becoming available for scrutiny. What kind of continuity do you sense despite the ruins depicted? Editor: Well, there’s a contrast between the promise of the new medium, photography, and the ruins representing a distant past. Perhaps Du Camp was pointing out a desire to grasp or even freeze a moment in time? Curator: Precisely. He uses that photographic "freezing" to try to preserve the evidence of great human events and cultural memory. Look at how he frames the built forms amidst nature. Are these structures rising up toward the sky or becoming enveloped back into the earth? The play of light on these eroding walls also suggests that the symbolism goes beyond just documenting their physicality. Editor: That makes me wonder about how people from his time and our own understand those buildings. If the landscape engulfs them, maybe it becomes a reminder of lost empires, fading memories. Curator: Exactly! Think of the long and fraught symbolic dialogue between the West and the East that played out at this time. We can recognize in Du Camp's image a psychological projection as well as a visual representation, allowing the Western viewers to situate themselves as superior in that dialogue, possessing the ability to contain ancient ruins through photography and interpret their hidden meanings. Editor: That’s a great point. Seeing it this way, the picture’s melancholy feels deeper, intertwined with a sense of historical power dynamics and a selective visual narrative. Curator: I’m glad you see it. Acknowledging those complicated narratives makes the past that much richer, doesn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.