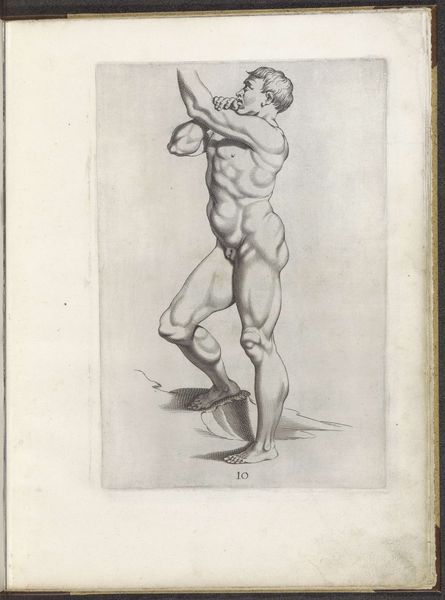

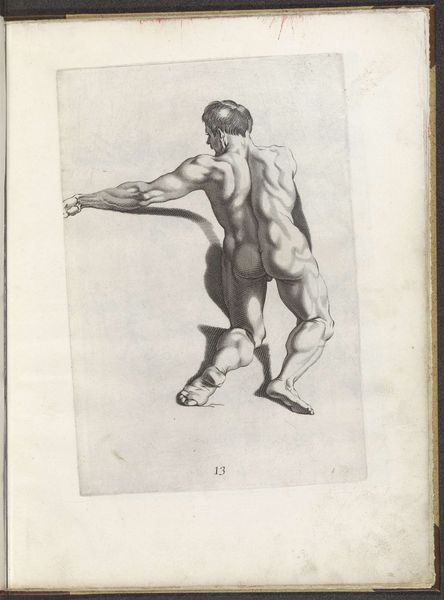

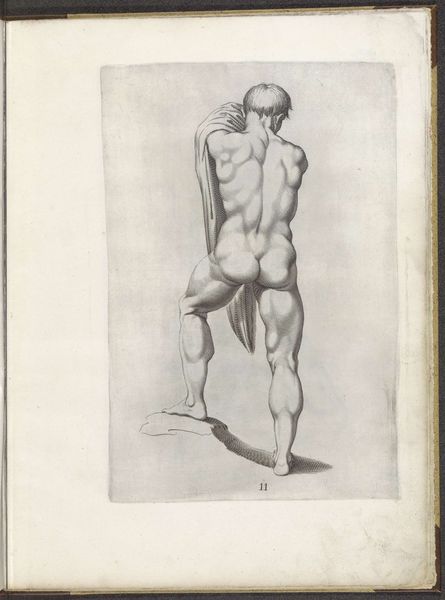

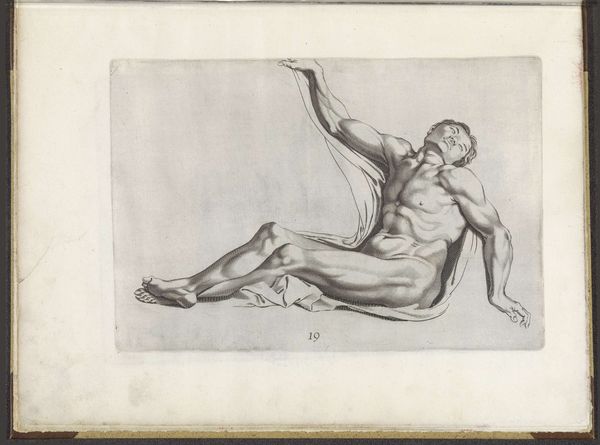

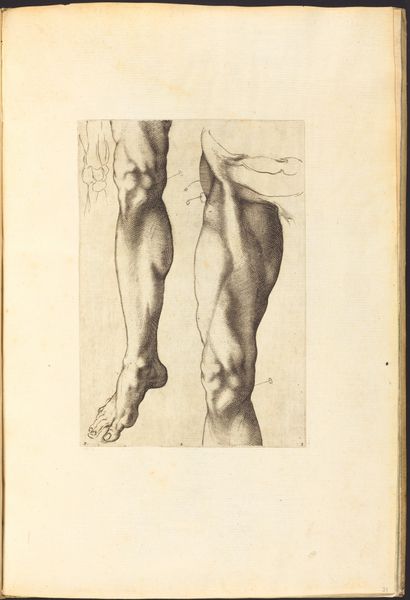

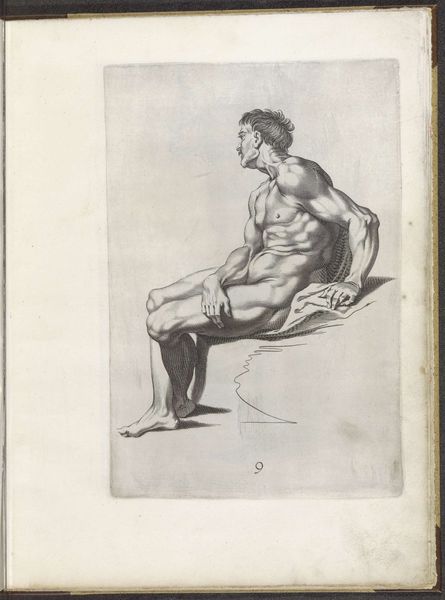

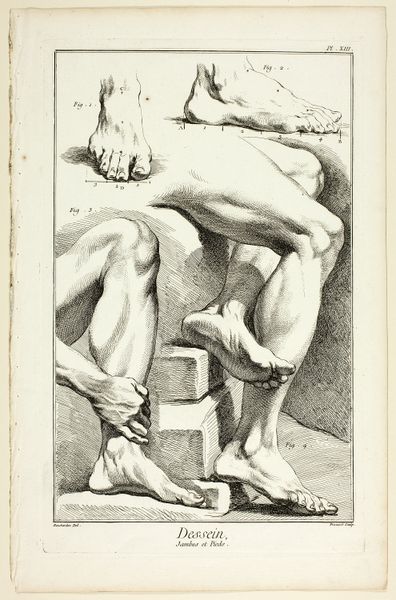

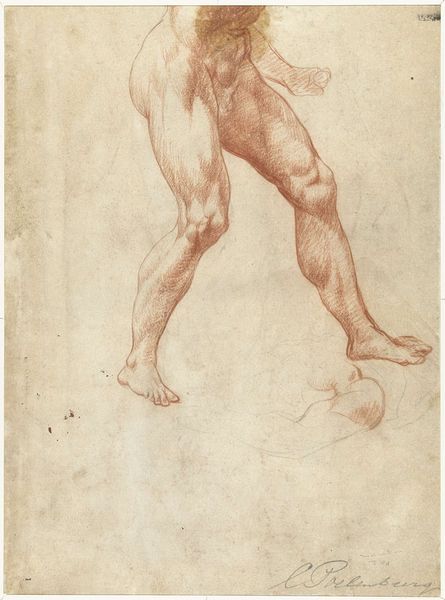

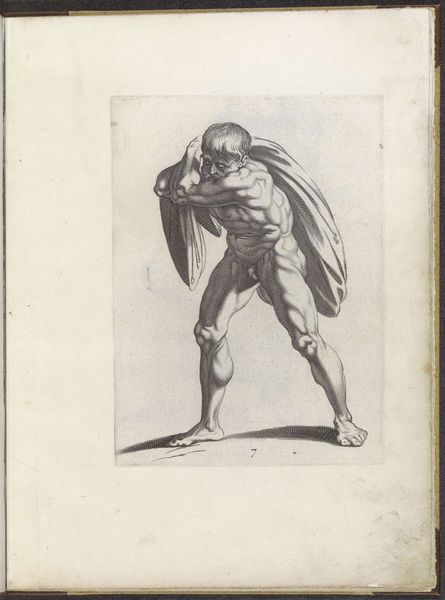

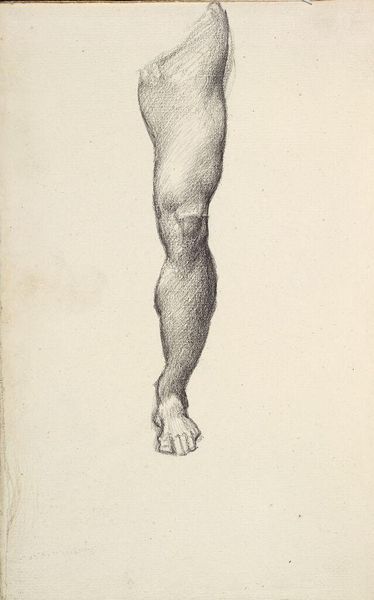

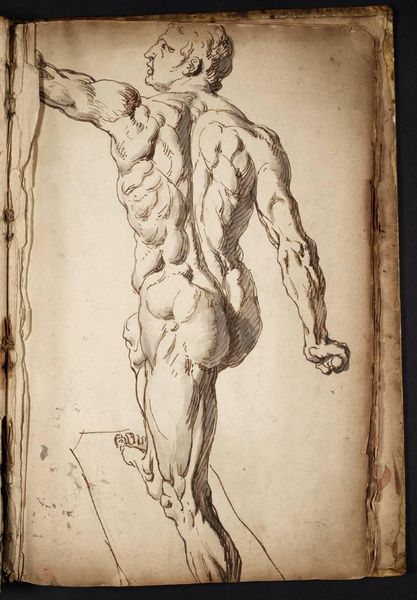

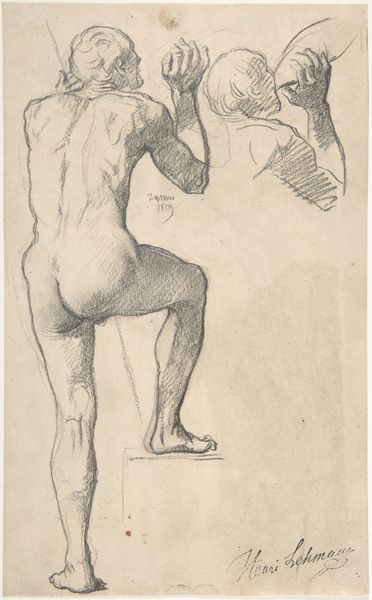

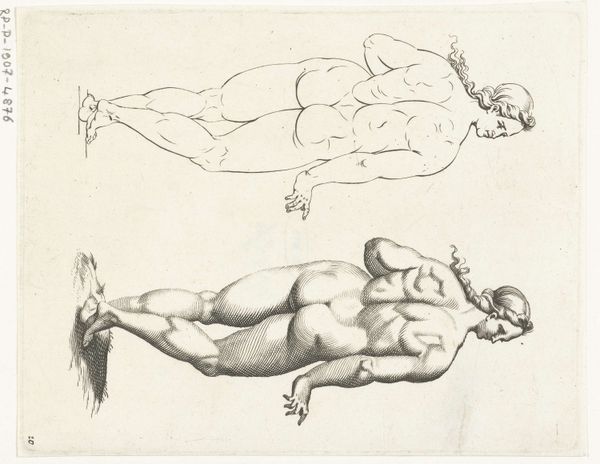

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

#

arm

Dimensions: height 270 mm, width 184 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is “Tekenvoorbeelden van armen en benen,” or “Drawing Examples of Arms and Legs,” created around 1629 by Pieter de Jode I. It’s an engraving on paper, currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression is of a sculptural study. The isolated limbs have a monumental quality despite the artwork’s probable small scale. There's a clear emphasis on musculature, almost anatomical in its precision. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the period. In the 17th century, prints like these were crucial for disseminating knowledge and artistic styles. They weren't just aesthetic objects, but pedagogical tools offering examples to aspiring artists. Editor: Focusing on the formal elements, I see the masterful use of line to create volume and shadow. The hatching technique is exquisite, defining the form with incredible detail and conveying a sense of depth. Curator: Indeed. These drawings served as models of idealized masculine strength. However, looking through a critical lens, one can observe a certain detachment. The absence of torsos creates a fragmented, almost disembodied vision of masculinity that speaks to ideas around power and vulnerability. Consider that the work’s title is literally, Examples. It seems Pieter de Jode the elder produced examples for others to emulate, a fascinating interplay of form, figure, and historical representation. Editor: I would agree about that level of remove. From a structuralist point of view, each limb operates almost as an independent signifier of strength, even desire, yet it lacks context. The semiotic reading suggests an objectification – an analysis reduced to component parts, devoid of complete humanity. Curator: Precisely, but consider also the act of artistic interpretation that comes after seeing this example, where these depictions get applied to the (almost always male) heroes, gods, or figures from history painted during the period. It raises questions of whose bodies get canonized and for what purposes. Editor: I concede the print's deeper sociocultural significance. Its pedagogical intention reveals its own historical bias – a very limited, if skillfully rendered, ideal. Curator: Agreed. It demonstrates the importance of recognizing prints and drawing not simply as artistic compositions, but as historical artifacts enmeshed within systems of knowledge, gender, and class. Editor: A reminder that even the most apparently formalist study inevitably holds implicit narratives. Thank you for illuminating those connections!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.