print, paper

# print

#

paper

#

text

#

11_renaissance

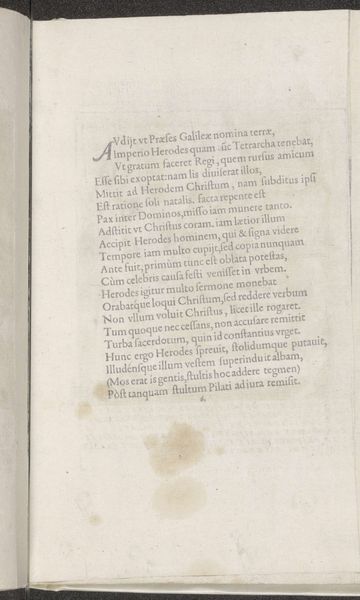

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have Domenico Mancini’s "Tekst over Christus voor Pilatus," created in 1572. It's a print on paper, and what immediately strikes me is the density of the text. It feels almost like a legal document more than a work of art, I'm curious, how does this relate to the broader history of imagery and power? Curator: That's an astute observation. Consider this print within the context of the Reformation and the rise of print culture. Text becomes a powerful tool for disseminating ideas, and in this instance, the story of Christ before Pilate isn't just a religious narrative, but a commentary on justice, authority, and truth. The image itself becomes secondary; the words carry the weight. How do you think its role is shaping a viewer’s experience, given this context? Editor: Well, if I wasn’t able to read Latin, I suppose I’d feel rather left out! Was it originally designed to sway the learned? Is it supposed to reflect who really has access to "Truth?" Curator: Precisely. It invites a particular audience—the educated elite—to engage with its arguments. Mancini’s choice of Latin positions this work within a specific intellectual tradition, signalling who has the authority to interpret religious and political events. Do you think this restricts or empowers the image's social impact? Editor: That’s complex! It’s exclusionary, sure, but also perhaps more deeply effective within its target demographic. It relies on and reinforces established hierarchies of knowledge and power. I guess it highlights the complex ways in which art serves the political agenda of its era. Curator: Exactly. By understanding the socio-political landscape of the time, we can unlock the multiple layers of meaning embedded within this seemingly simple print. The ‘politics of imagery’ includes printed text. It certainly gives me food for thought.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.