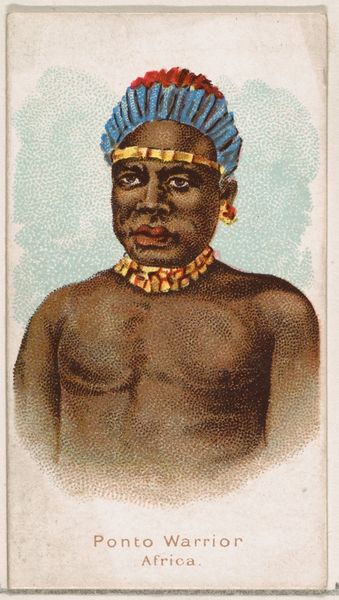

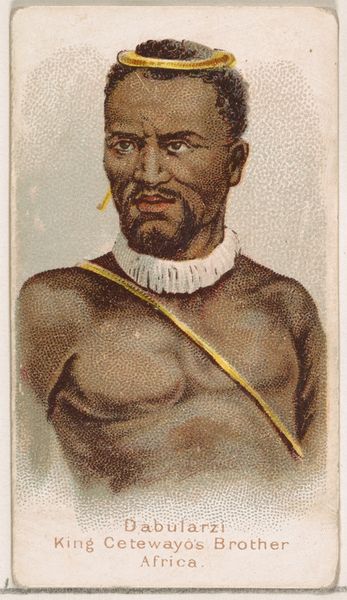

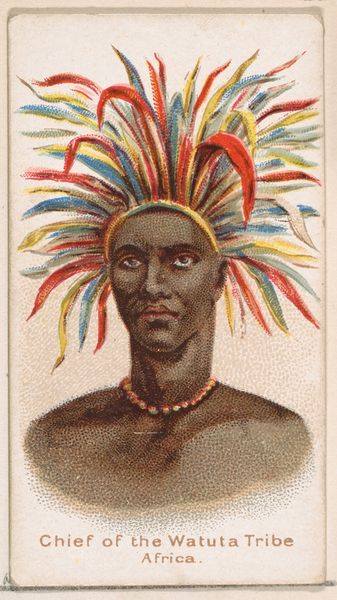

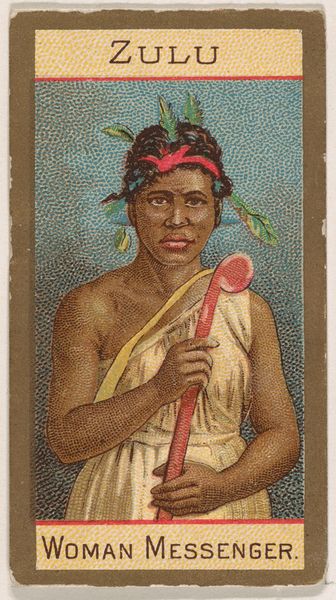

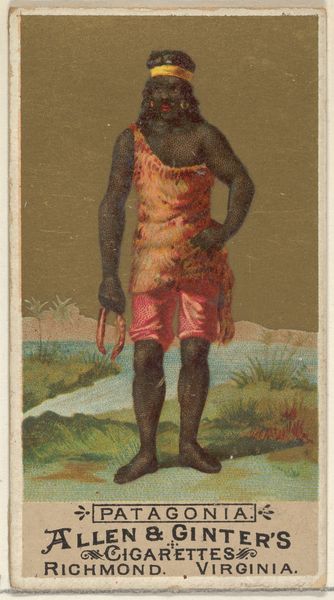

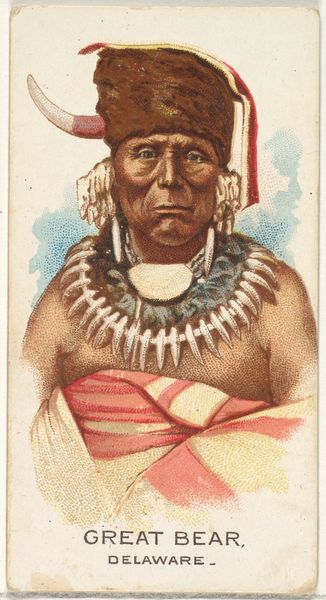

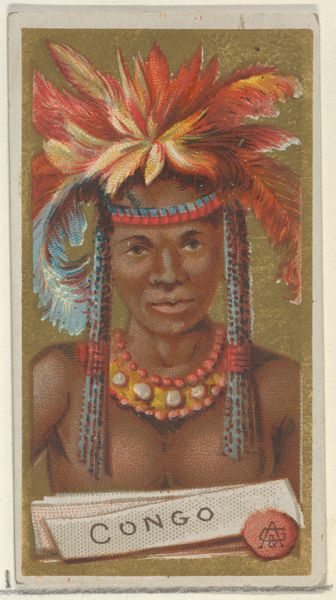

King Cetewayo, Zulu King, Africa, from the Savage and Semi-Barbarous Chiefs and Rulers series (N189) issued by Wm. S. Kimball & Co. 1888

0:00

0:00

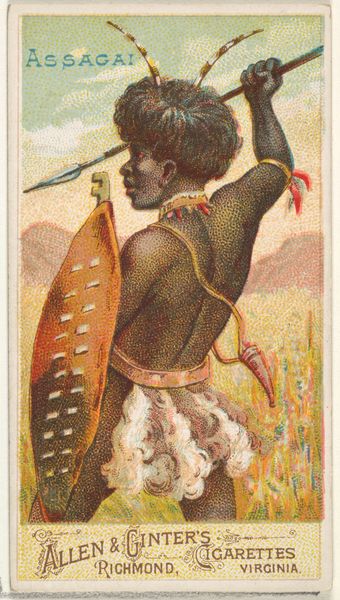

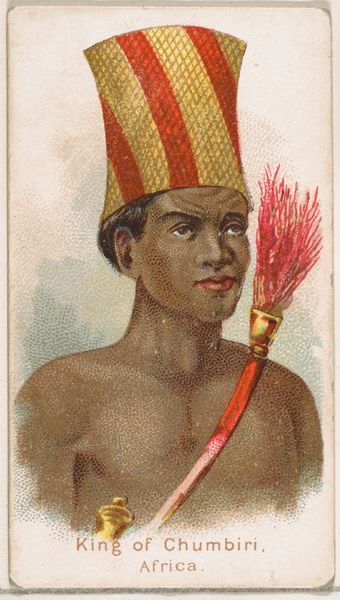

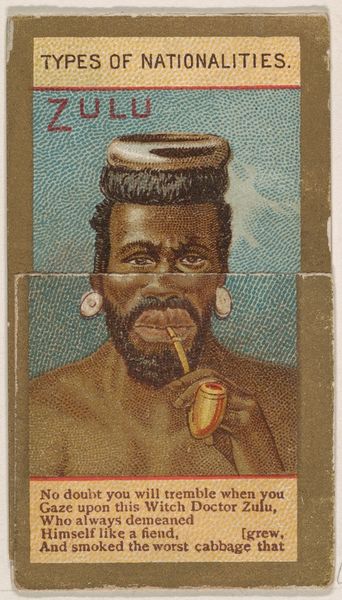

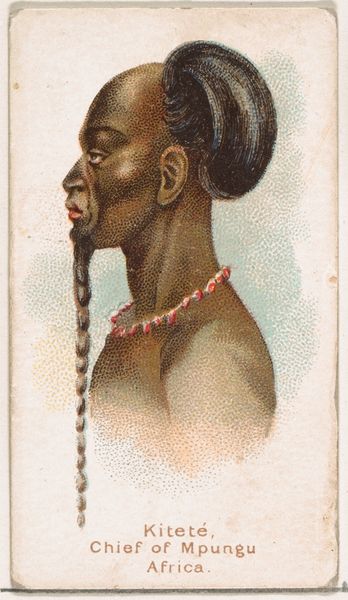

drawing, coloured-pencil, print

#

portrait

#

african-art

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

# print

#

coloured pencil

Dimensions: Sheet: 2 11/16 × 1 1/2 in. (6.8 × 3.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is an 1888 print of King Cetewayo, the Zulu King, part of a series called "Savage and Semi-Barbarous Chiefs and Rulers" made by Wm. S. Kimball & Co. The title itself already tells us so much about how he was viewed by the West, doesn’t it? What strikes you when you look at this piece? Curator: It's vital to recognize how this image functioned as a tool of colonial ideology. The title and the series it belongs to reveal deeply entrenched racist perspectives of the time. Note the paternalistic way in which King Cetewayo is represented and how this presentation serves to "other" and demean him. This imagery justified colonial expansion by portraying non-European leaders as inherently inferior. What can we tell about how race, power and representation intersect when looking at this drawing? Editor: So the way he’s portrayed as almost exotic is actually a power play? Like, they’re emphasizing differences to justify their own actions? Curator: Exactly. And consider the details – the feathers, the jewelry – they’re exoticized, but also somewhat flattened, losing the nuance and meaning they would hold within Zulu culture. How might these symbols be misinterpreted or misrepresented by a Western audience, and what impact would that have on perceptions of Zulu people and their society? Editor: It's like taking away his agency, his own story. Instead, it's giving him this label, making him fit into their narrative. Curator: Precisely. It's a powerful example of how images can perpetuate harmful stereotypes and contribute to systems of oppression. It forces us to consider the ethical responsibilities we have when engaging with such loaded historical artifacts. Do you agree with that point of view? Editor: I absolutely do! It makes you realize that looking critically isn't just about aesthetics; it's about unpacking the baggage that comes with these images. Curator: Yes, that's how we can connect the art to a broader analysis of society, encouraging critical thought and awareness around historical narratives and contemporary forms of representation. It’s far more than just a portrait, it’s a lesson about how colonial attitudes have affected entire cultures.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.