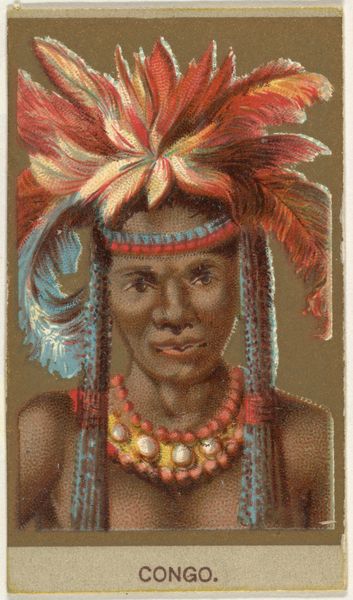

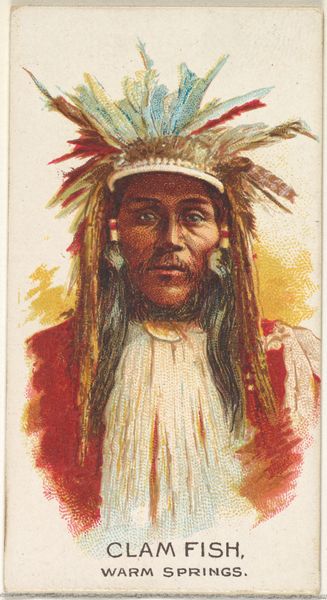

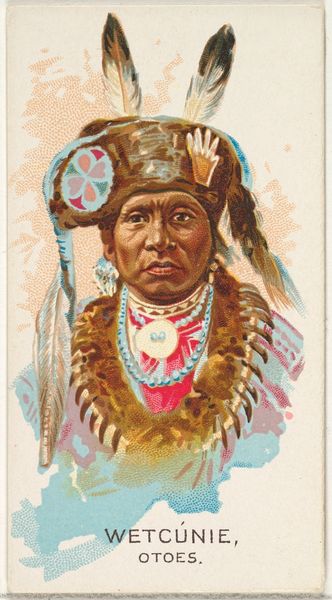

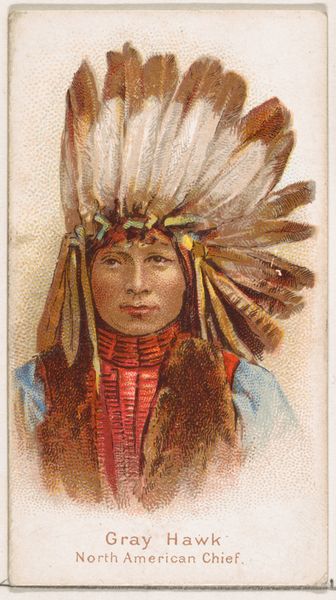

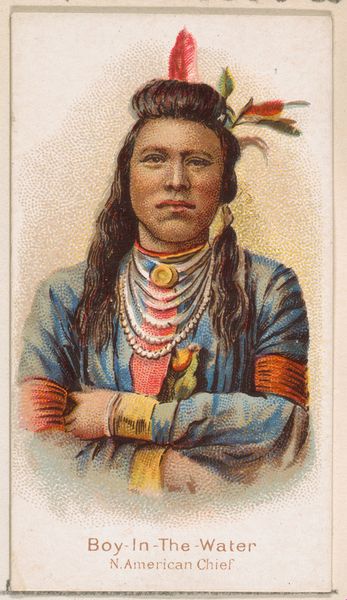

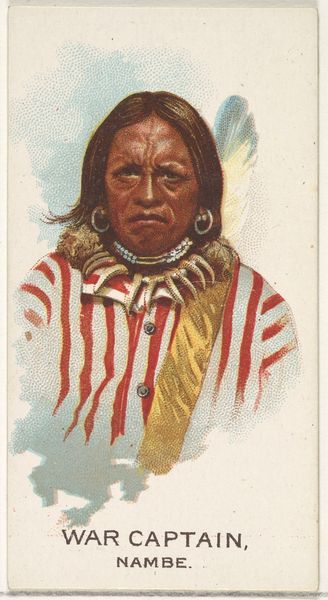

Congo, from the Types of All Nations series (N24) for Allen & Ginter Cigarettes 1889

0:00

0:00

drawing, coloured-pencil, print

#

portrait

#

african-art

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

# print

#

coloured pencil

#

men

#

realism

Dimensions: Sheet: 2 3/4 x 1 1/2 in. (7 x 3.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

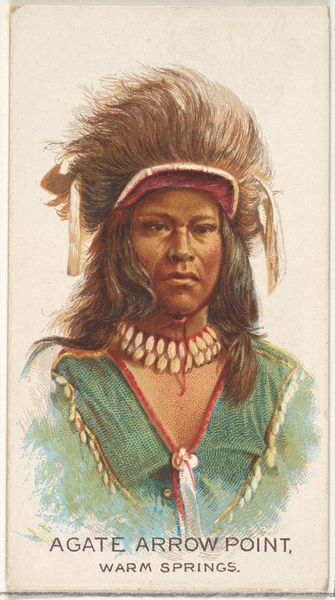

Editor: So, this is "Congo, from the Types of All Nations series," created in 1889 by Allen & Ginter, using colored pencils and print. It’s quite small, like a trading card. I’m immediately struck by the vibrancy of the feathers and jewelry against what appears to be a more subdued background. What jumps out at you about this piece? Curator: Well, immediately, I consider the context of its creation. Allen & Ginter were a tobacco company. So, how does the creation and distribution of this image as a collectible within cigarette packs shape its meaning and impact? It becomes less about representing an individual and more about... Editor: Exoticizing them? Curator: Exactly. Consider the series title: "Types of All Nations." It's inherently categorizing and framing people within a Western gaze, reducing cultures to a consumable "type." The image reinforces colonial power dynamics. Notice how the subject is presented? Centered, direct gaze, but without agency. Does the artist seem truly interested in portraying this individual or just using them as a symbol? Editor: I see what you mean. It feels less like a respectful portrait and more like… a specimen. How might this image have impacted public perceptions of Congolese people at the time? Curator: These images were widely distributed and seen. It reinforced existing stereotypes and justified colonial expansion and exploitation. The vibrant colors might have been meant to attract consumers, but they also create a distorted, almost cartoonish image of Congolese culture. We must critique the ethics and impact of images like these, acknowledging their role in perpetuating harmful narratives. Editor: That's incredibly insightful. I hadn’t considered the implications of it being a cigarette card, but it makes complete sense. I'll definitely look at these types of historical images differently now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.