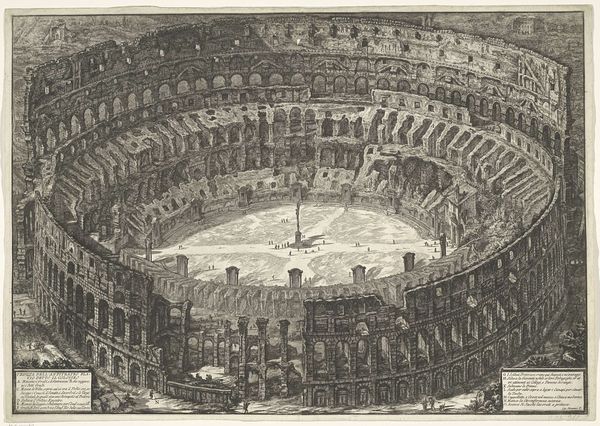

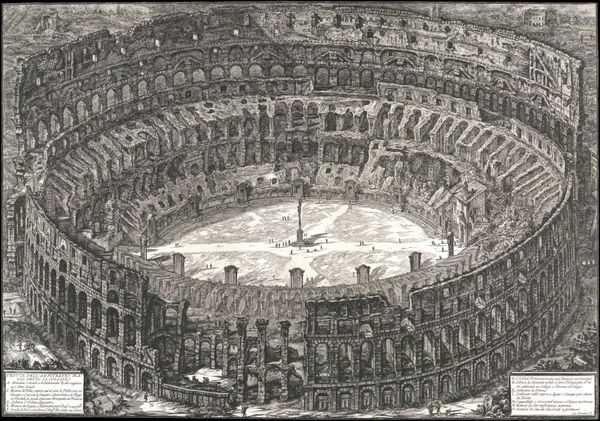

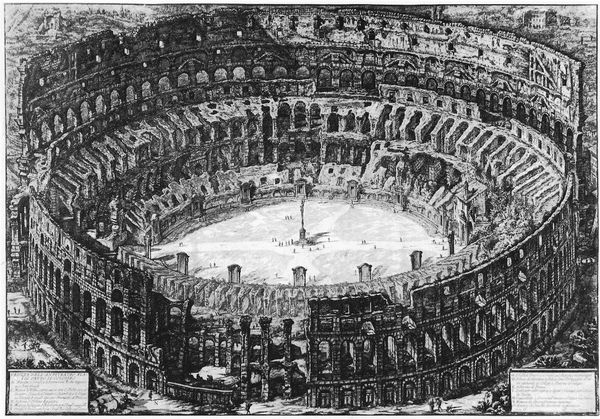

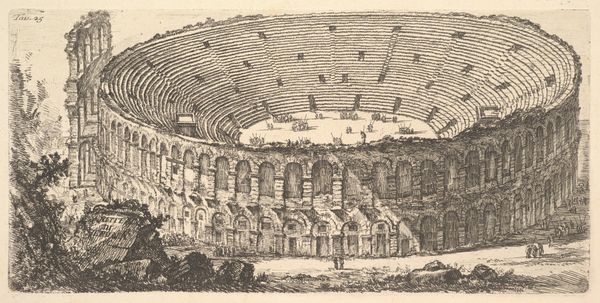

print, etching, engraving

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

romanesque

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: 19 3/8 x 27 5/8 in. (49.21 x 70.17 cm) (plate)21 3/8 x 30 3/8 in. (54.29 x 77.15 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

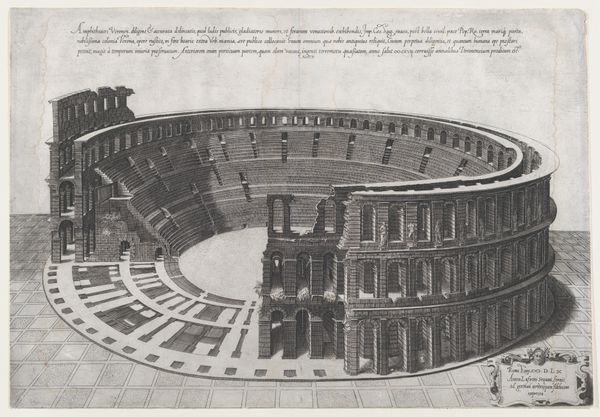

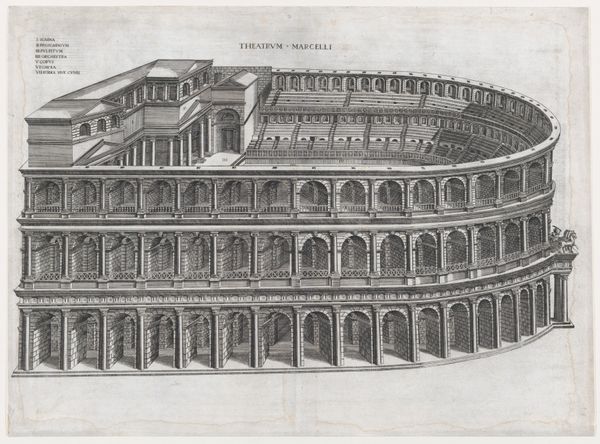

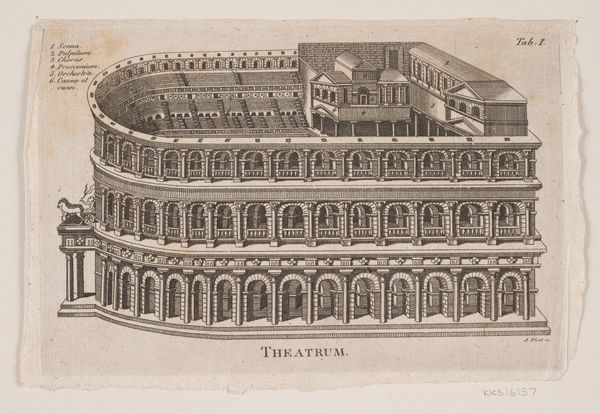

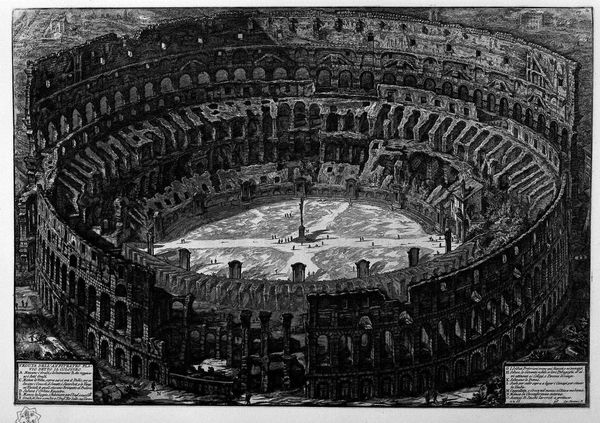

Curator: This is Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s "View of Flavian Amphitheater," a print created through etching and engraving in 1776. It is currently housed here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: The sheer scale depicted is quite overwhelming, isn’t it? You feel the weight of history pressing down, yet also, surprisingly, a sense of haunting emptiness. Curator: I think the effect you are describing has a lot to do with Piranesi's technical approach. The stark contrasts achieved through etching emphasize the texture of the stone and the play of light and shadow, turning mere material into a visceral experience. Editor: And the way he plays with perspective, dwarfing those tiny figures in the arena. It's as if he’s hinting at the insignificance of individual lives against the backdrop of Roman imperial ambition and its eventual decline. The Colosseum itself is a potent symbol of both power and the transience of that power. Curator: Indeed. Piranesi was deeply interested in Roman antiquities and their physical state. You see the labor inherent in both the creation and the decay. What social forces were at play? The political narratives imposed and then the natural processes that inevitably break things down… it's all embedded in the materiality of this print. Editor: You make a good point. Even the very deliberate artistic choices made, serve to both represent and transform a cultural monument. Each mark and shade of the engraving invites us to meditate on those earlier lives, and how this architectural emblem embodies so many historical and symbolic strata. Curator: Exactly! By examining his printmaking methods and subject matter, we see how Piranesi reinterpreted history and left us with a meditation on production, consumption, and ruin. Editor: It is truly thought-provoking. Now when I look at this work, it's not just an amphitheater depicted here, but a reflection on time, ambition, and mortality itself.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

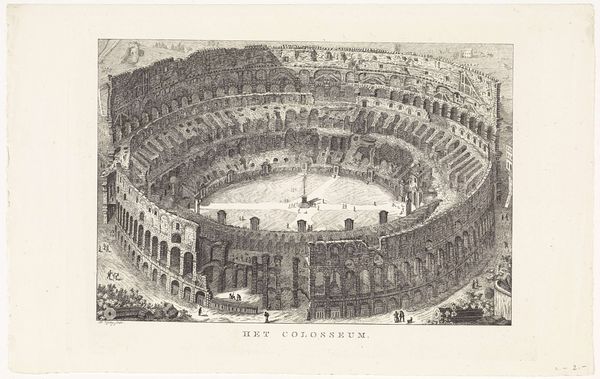

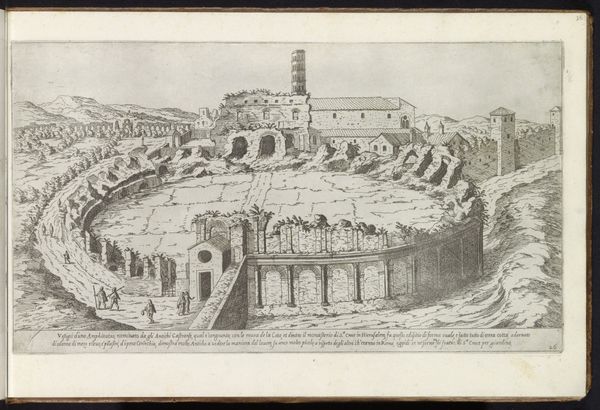

Gladiator combats, wild-animal hunts, executions—all manner of spectacle took place inside the Colosseum, which could hold up to 80,000 people. It was even filled with water to hold mock naval battles. After Rome’s decline, the Colosseum was seen as a ready source of building materials, and people plundered its great façade and interior. The quarrying was stopped in Piranesi’s time by Pope Benedict XIV, who mistakenly believed that the place was a site of Christian martyrdom.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.