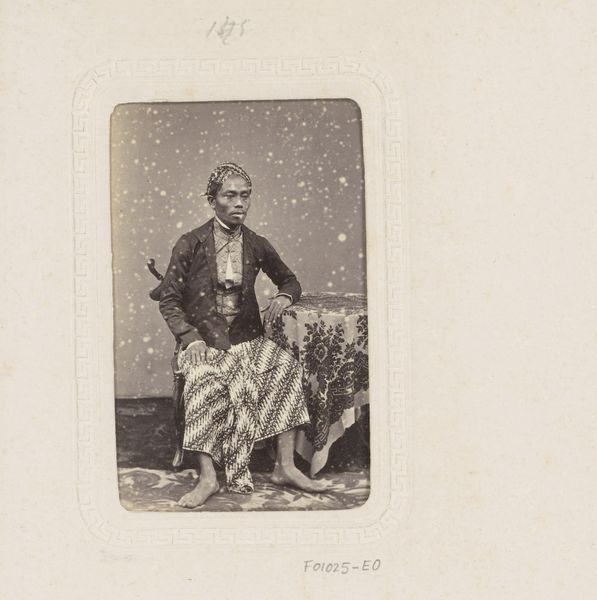

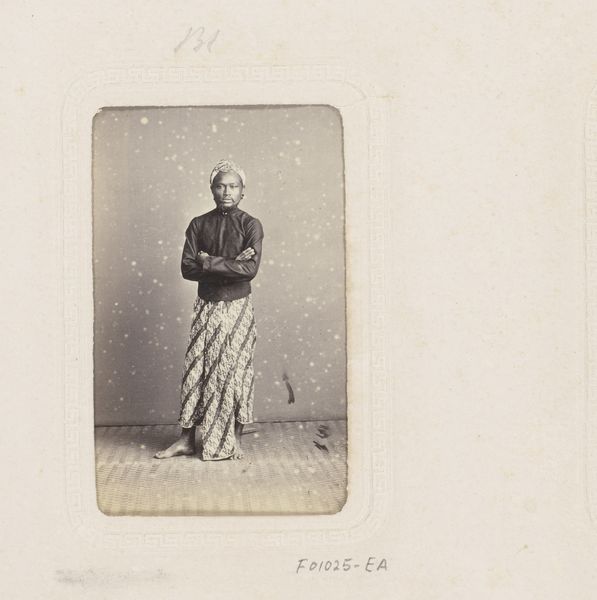

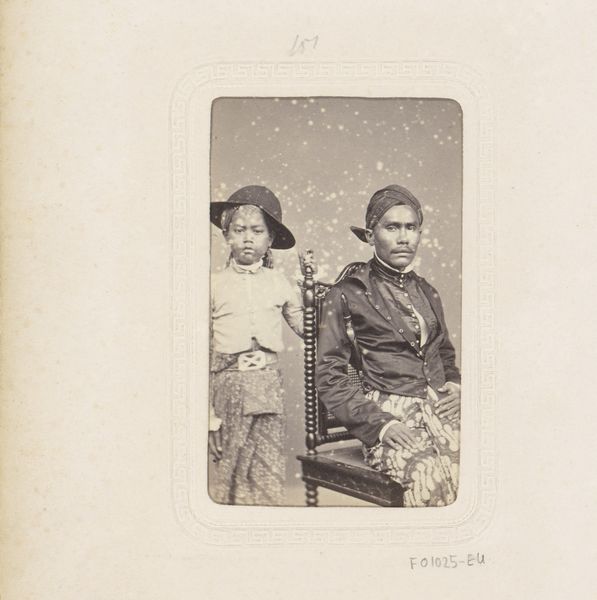

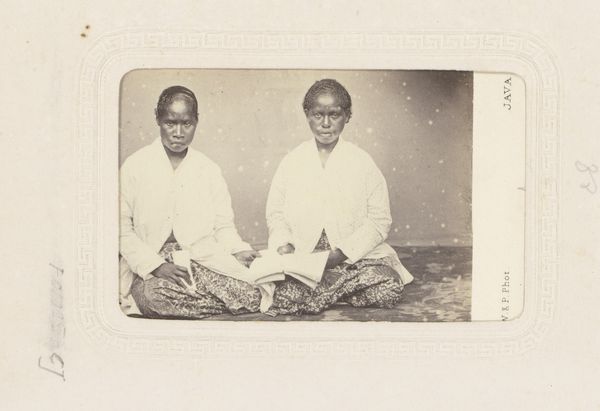

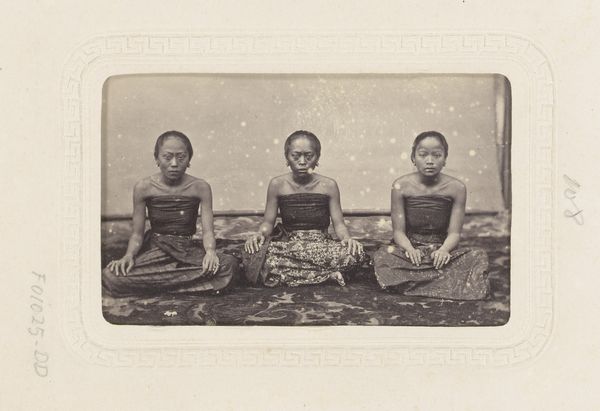

Portret van vermoedelijk een bediende van Hamengkoeboewono VI met twee kinderen 1857 - 1880

0:00

0:00

woodburypage

Rijksmuseum

albumen-print, photography, albumen-print

#

albumen-print

#

portrait

#

asian-art

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

old-timey

#

19th century

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 85 mm, height 52 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

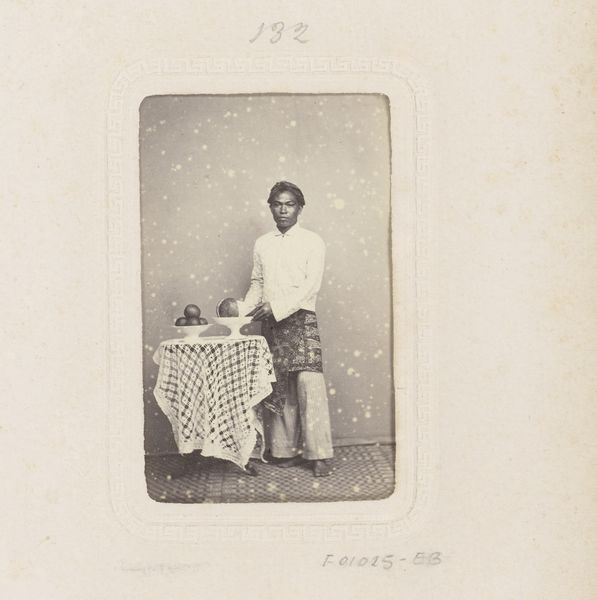

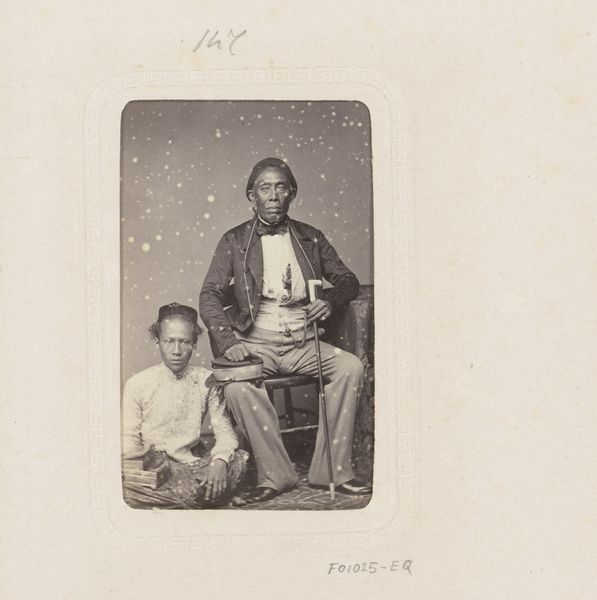

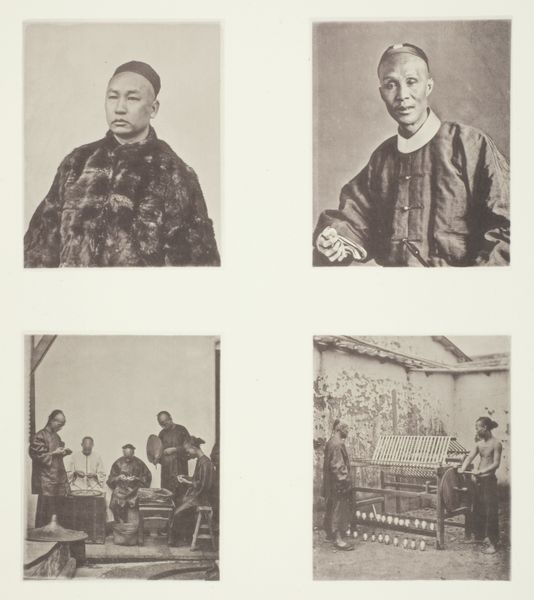

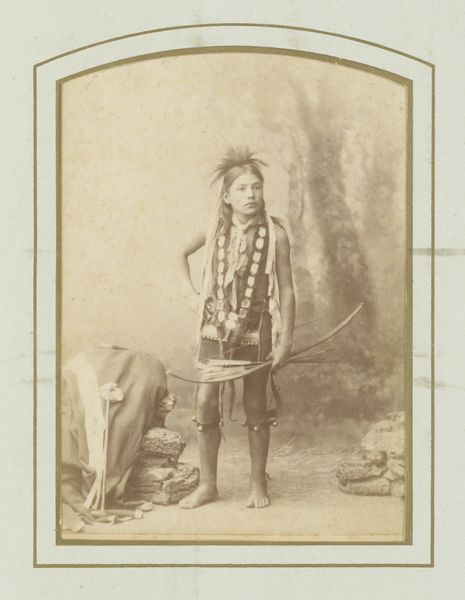

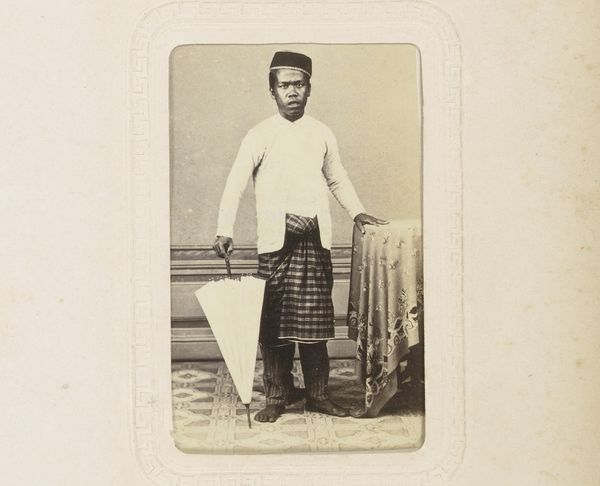

Editor: This is a photograph entitled "Portret van vermoedelijk een bediende van Hamengkoeboewono VI met twee kinderen," created between 1857 and 1880 by Woodbury & Page. It's an albumen print, currently held at the Rijksmuseum. I'm immediately struck by the formality of the composition, and the direct gazes of the subjects. What social dynamics do you think are at play here? Curator: That's a great question. Considering its context, Java during the colonial period, we must unpack the power dynamics inherent in such a portrait. It's crucial to recognize that Woodbury & Page were European photographers operating within a system of colonial exploitation. Editor: So, the very act of documenting these individuals was influenced by colonialism? Curator: Precisely. While seemingly a straightforward portrait, it becomes a complex statement about representation, agency, and cultural exchange. Whose gaze is centered here? What does it mean to capture the likeness of individuals labeled as 'servants' within the framework of imperial authority? What survives of their identity? The children's proximity makes the relationships feel complicated, doesn't it? Editor: Definitely. The backdrop seems very generic, focusing solely on the sitters. I wonder if that adds to the objectification? Curator: It may. Consider also the prevalence of Japonisme and the fascination with Asian art during that era. Could this image be viewed through that lens, as an exoticized depiction of Javanese individuals tailored for Western consumption? Editor: That's fascinating. It makes me question my initial reading of formality. Curator: These photographs provided Europeans with a sense of knowledge and ownership over the colonized world, creating an imbalance of power that persists even today. By recognizing that, we create space to better know ourselves. Editor: I hadn't thought about the enduring legacy of those power dynamics. This gives me a lot to consider about representation and the colonial gaze in 19th-century photography. Curator: Exactly, it’s crucial to think critically about whose stories are being told, and how, in art historical narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.