drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

form

#

pencil

#

line

#

realism

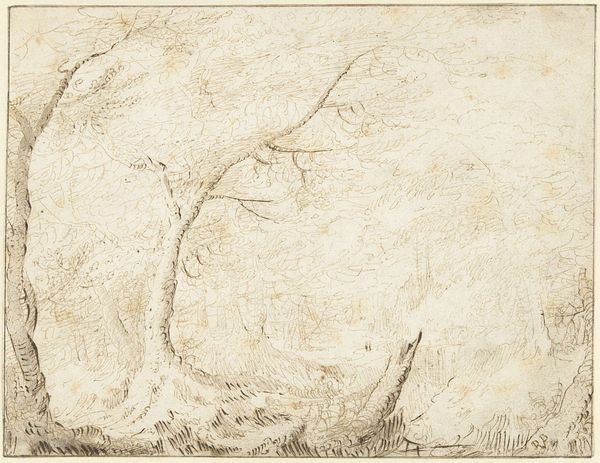

Dimensions: height 252 mm, width 297 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Anthonie Waterloo's "Sketch of a Landscape with Three Trees," created sometime between 1619 and 1690. It's a pencil drawing and there's something really calming about its simplicity, its unpretentious representation. What do you see when you look at it? Curator: I'm immediately struck by the physicality of the drawing itself. We're looking at the residue of labor, aren't we? Consider the accessibility of pencil in that period; what did it mean to depict landscapes using such readily available materials, compared to the grand oil paintings of the time? Editor: So, it’s not just about the trees themselves, but the act of *drawing* these trees and what that signified? Curator: Precisely! Waterloo wasn’t just capturing the likeness of trees; he was engaging in a specific kind of artistic production. Who had access to these materials, and who was excluded? How does this simple drawing participate in the broader economic and social landscape of its time? Think about the paper itself. Its production, its cost, its distribution... Editor: It sounds like you're saying that even this sketch has a connection to industry and social class? Curator: Absolutely! We must challenge the traditional boundaries of "high art." The very *thingness* of art objects, their materiality, links them inextricably to the economic and social relations of their time. This piece invites questions about access, labor, and the consumption of imagery. Editor: I never considered it that way. I guess I always thought of sketches as simple preparation for other things, and now I see them as also holding social meaning themselves. Thanks. Curator: The sketch, as a material object, has the power to show the artist's method, labour, and accessibility that other media does not. Food for thought, isn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.