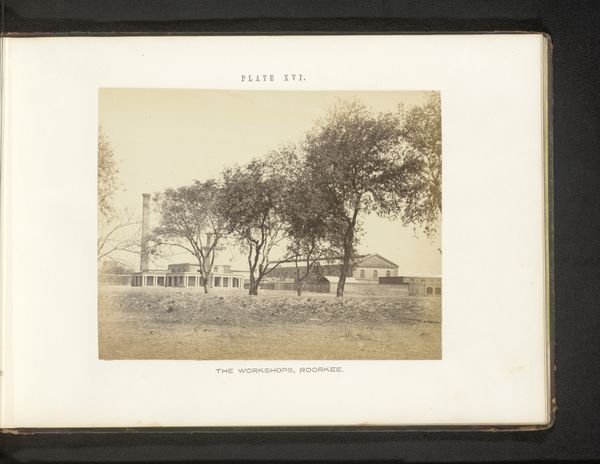

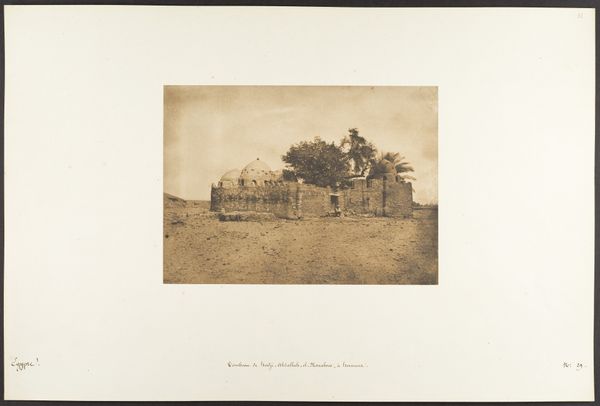

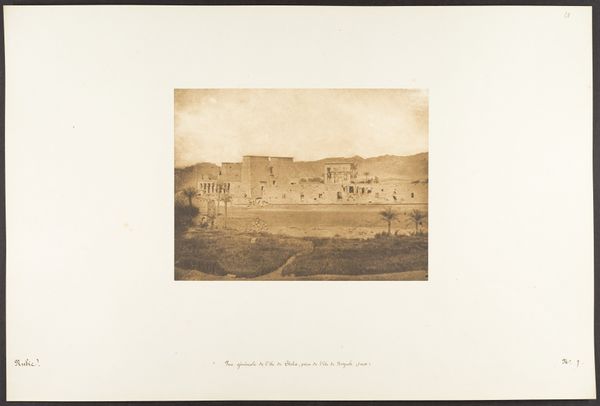

Vue du Divan et du Palais du Gouverneur, à Syout 1849 - 1850

architecture

thick outline

script typography

hand drawn type

hand-drawn typeface

arch

thick font

pale shade

delicate typography

tonal art

thick lined

architecture

small font

Dimensions: Image: 5 9/16 × 8 1/2 in. (14.2 × 21.6 cm) Mount: 12 5/16 × 18 11/16 in. (31.2 × 47.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Maxime Du Camp captured this scene in his 1849-1850 photograph titled "Vue du Divan et du Palais du Gouverneur, à Syout," now residing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The title translates to "View of the Divan and the Governor's Palace in Asyut," and it immediately makes me consider the photographic gaze and its relationship to colonial power. Editor: It strikes me as deceptively placid at first glance, but with that in mind, I now recognize an unsettling calm. This architectural structure seems…distant, set apart. Curator: Du Camp, working so early in photography’s history, presents this official building— the Governor’s Palace and the divan, a council chamber—with a clarity that must have held profound symbolic meaning for its time. Light, perspective, and composition give us clues to the cultural status it was imbued with. The choice of sepia tones suggests permanence, linking new technologies to older artistic styles, while the symmetrical repetition and clear architectural detailing are reminiscent of Neoclassical principles which in turn relate back to an imperial vision and authority. Editor: Yes, and I'm seeing it too now, the palace's form and situation reflecting both a promise and an unspoken warning. Architecture is never neutral; its intent—its symbolism—is intertwined with how space is negotiated by the public and authorities. I wonder about the experience of inhabiting or even approaching this building, particularly for those whose lives were governed from within. Curator: We also should not forget this image acts as documentation of place during France's colonial presence in Egypt. The Divan’s purpose to meet with officials is quite loaded considering this historical context. How were the interests of locals represented fairly under duress? Du Camp gives us clues into the setting, yet what can’t be shown can also reveal important insight, like how local officials had limited power and colonial power outweighed Indigenous control. Editor: And considering the photographic project as a whole – the act of surveying, cataloging, claiming spaces visually – we begin to see the apparatus of power extending beyond the physical buildings themselves. It's a layered reading, indeed, from what might initially appear simply documentary. It reminds us that all art is enmeshed within sociopolitical forces whether intended or not. Curator: Ultimately, reflecting on how symbols are perceived through the shifting sands of time can alter meaning, giving rise to renewed questions, especially in regard to postcolonial studies.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.