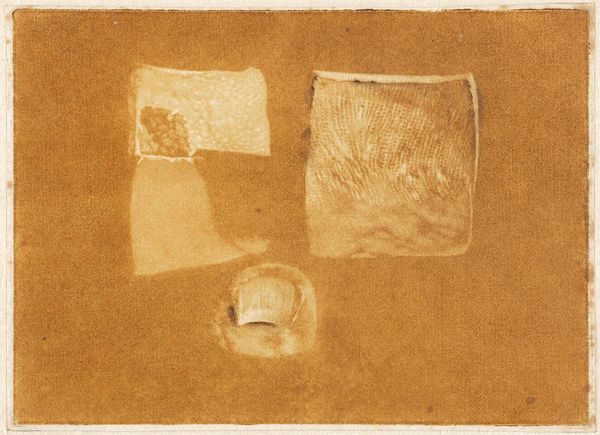

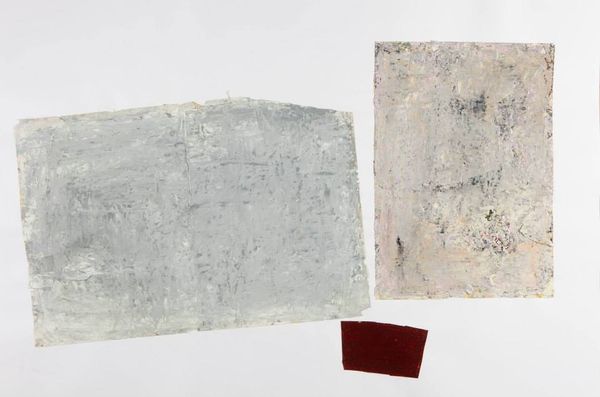

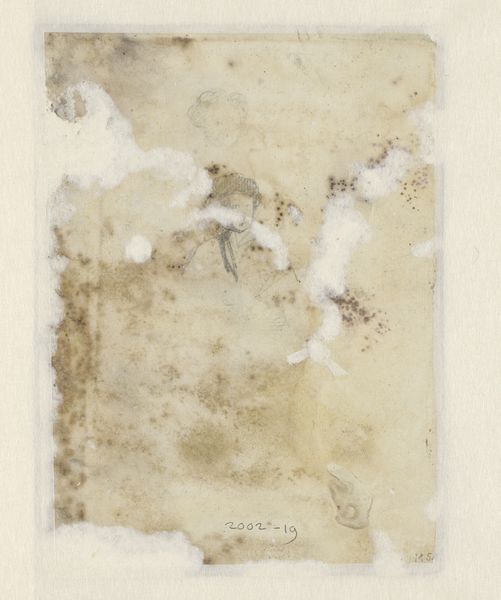

drawing, paper, watercolor

#

portrait

#

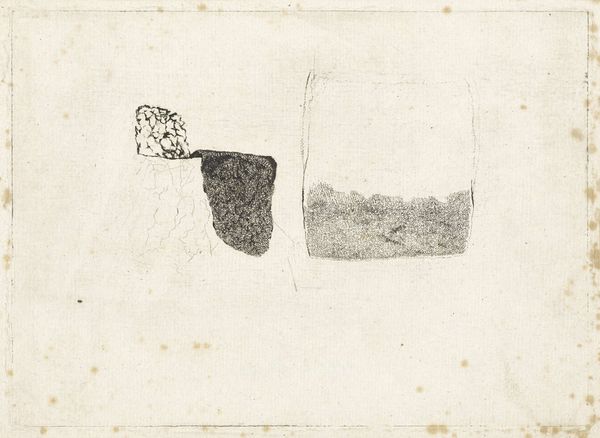

drawing

#

baroque

#

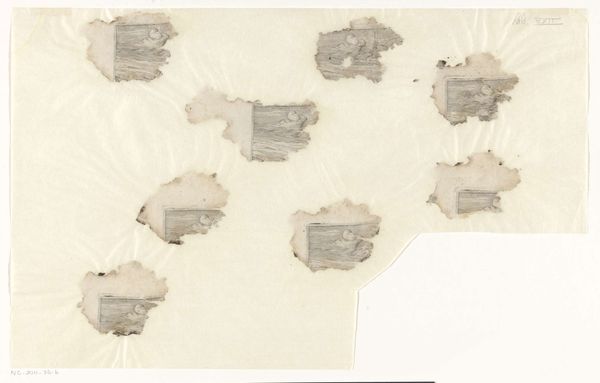

paper

#

watercolor

#

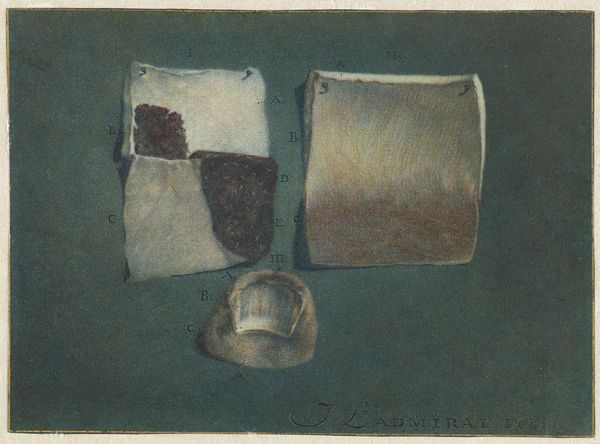

coloured pencil

#

academic-art

#

mixed media

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 117 mm, width 146 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Jan l'Admiral’s "Top View of a Child’s Fontanel | Anatomical Study of Human Skin and Nail" created in 1737. It’s a watercolor and mixed media drawing on paper. I find the almost clinical detachment a bit unsettling, considering the subject matter. What’s your take on this? Curator: Unsettling is a great word for it. Imagine being l’Admiral, peering so closely at the ephemeral, the vulnerable. He wasn’t just documenting; he was engaging with the mystery of human development. Look how he's meticulously rendered the texture, the almost paper-thin fragility. Does it strike you as scientific, or something more... contemplative? Editor: Contemplative is interesting. It feels objective, yet that focus suggests something beyond pure observation. The subdued colours add to that, maybe? Curator: Exactly! The colours drain away the vibrancy of life. It speaks of the era's fascination with dissecting, understanding the body, but perhaps with a hint of melancholy too. The Baroque loved drama, but even scientific illustration couldn't escape the shadow of mortality, could it? Editor: That's true. I hadn't thought of it that way, as a sort of *memento mori* for infancy. Is that overreading it? Curator: Perhaps a little dramatic, but all readings are valid as it depends on us, doesn't it? Maybe l'Admiral saw a fragile promise, knowing what time inevitably takes away. Thank you! It is also true that this piece seems so much more emotionally intricate now. Editor: I agree. Seeing it through that lens really adds another layer to the work. It makes me appreciate how art, even seemingly clinical art, can hold such unexpected depth.

Comments

rijksmuseum almost 2 years ago

⋮

Commissioned by doctors, Jan l’Admiral made detailed anatomical design drawings, of which he later made prints to illustrate their medical treatises. He probably chose parchment because the ‘living’ character of the material suited the subjects. The skull belonged to an unknown child who died before birth. The skin was that of an Ethiopian woman, which begs the question of how the doctors obtained their study materials.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.