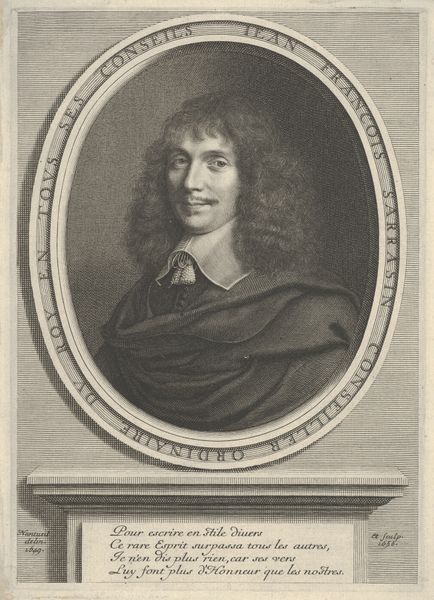

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

# print

#

men

#

engraving

Dimensions: image: 14 3/8 x 10 1/16 in. (36.5 x 25.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Jean Morin’s engraving, “Armand de Bourbon-Conti, prince du sang,” completed sometime between 1605 and 1650, presents us with an intriguing study in power and presentation. It’s currently housed here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: There’s an undeniable vulnerability here, despite the obvious markers of status. That soft gaze and the way the light catches the silk... it suggests a complicated inner life. Curator: Absolutely. This portrait exists within a specific socio-political context. Armand de Bourbon-Conti, a Prince of the Blood, held a privileged position, yet he lived during a time of intense religious and political upheaval in France. The Fronde, the civil wars...his life wasn't untouched by them. The artist made a statement on the role of leadership at that moment. Editor: The symbol at the base, though—the crowned "B" framed by laurel—firmly reasserts the Bourbon claim. I am immediately reminded of contemporary royal portraiture, and their symbolic languages of power. What this communicates in visual language echoes over centuries! Curator: Yes, the visual markers of lineage are quite striking, but consider how Morin complicates the narrative. By imbuing the prince with such softness, the artist seems to challenge conventional notions of masculinity and authority within that historical moment. He layers different aspects of Armand's personality, challenging us not to immediately categorize or take his privilege at face value. Editor: It's interesting to consider the portrait not just as a record, but as a crafted image meant to communicate specific virtues: piety shown through the cross pendant, status with the finery. The artist must have been attuned to conveying these traits, contributing to the sitter’s legacy. Curator: Exactly. And beyond the symbols, consider the psychological dimension: the soft lines, the melancholic eyes... It begs questions of how we understand representations of power and privilege today, particularly in the context of ongoing conversations about equity and access. How do we create new representations for leaders, who we select, and why? Editor: The artwork's power is sustained because of these various aspects. Seeing symbols, observing texture, and questioning meaning have allowed us to understand its message and history together.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.