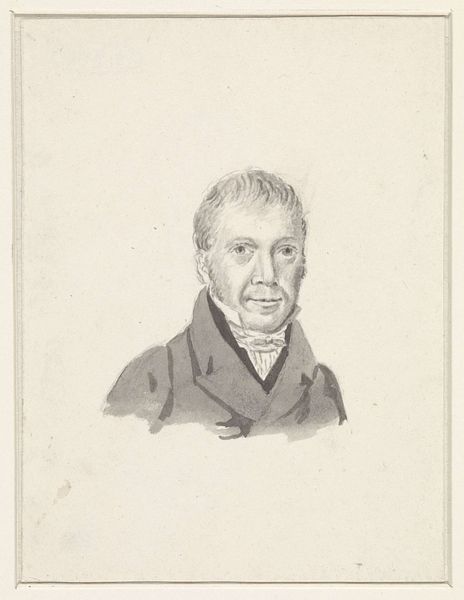

drawing, pencil

#

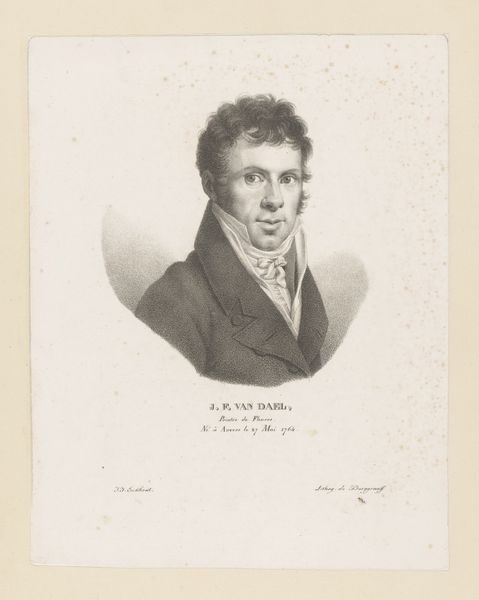

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

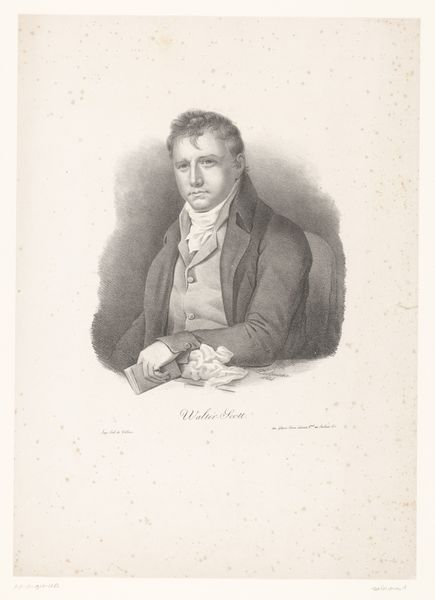

neoclacissism

#

pencil sketch

#

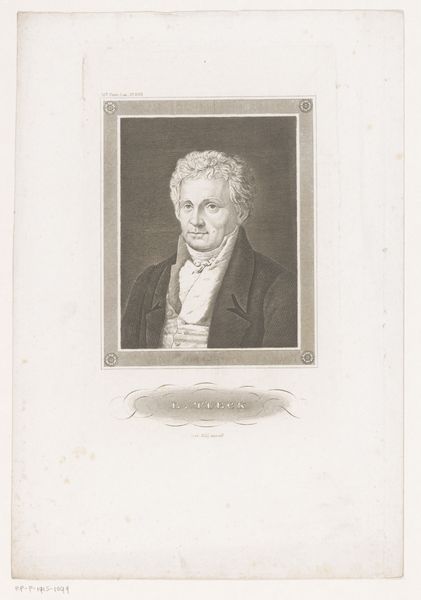

old engraving style

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 224 mm, width 142 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Jacob Ernst Marcus’s "Portret van Cornelis Loots," created in 1818. It's a pencil drawing, very precise and detailed. There’s almost a photographic quality despite being created over two centuries ago. How would you interpret the piece? Curator: What immediately strikes me is the intersection of Neoclassicism with the rising tide of Realism in the early 19th century. The clean lines and emphasis on rationality align with Neoclassical ideals. But it's important to ask: whose rationality is being presented here? Look at the detail in the sitter’s clothing versus the bare background. Editor: I see what you mean. It almost feels staged. The subject, Cornelis Loots, appears to be a man of stature. Is the detail, you mentioned, then meant to signal his importance? Curator: Precisely! And beyond the sitter's personal importance, this reflects a societal value placed on portraying figures of power and influence in a particular light. It’s not just a likeness; it's a construction of an image that reinforces specific social structures. Think about how art served the establishment. Editor: So, in that light, a pencil drawing is maybe more accessible and more easily distributed than an oil painting? Does that contribute to it having a public role? Curator: Exactly. This touches upon how images, in their varying forms, shape public perception. Portraits like these played a role in forming a collective understanding of who was considered important and why. The rise of printmaking made portraits far more accessible. Editor: This really makes you think about how artistic choices reinforce or even challenge the norms of their time! Curator: Indeed! Considering art as a reflection and constructor of social and political ideologies changes everything.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.